Because Thomas had given his life to defend the independence of the Church from undue interference by the civil power, King Henry VIII had the shrine destroyed in 1538, and forbade all devotion to him, even requiring that every church and chapel named for him be rededicated to the Apostle Thomas. The place within Canterbury Cathedral where the shrine formerly stood has been empty ever since; this video offers us a very nice digital recreation. Like the nearly contemporary shrine of St Peter Martyr and several others, the casket with the relics rests on top of an open arched structure, so that pilgrims can reach up and touch or kiss it from beneath, without damaging the metal reliquary itself.

Monday, July 07, 2025

The Translation of St Thomas Becket

Gregory DiPippoBecause Thomas had given his life to defend the independence of the Church from undue interference by the civil power, King Henry VIII had the shrine destroyed in 1538, and forbade all devotion to him, even requiring that every church and chapel named for him be rededicated to the Apostle Thomas. The place within Canterbury Cathedral where the shrine formerly stood has been empty ever since; this video offers us a very nice digital recreation. Like the nearly contemporary shrine of St Peter Martyr and several others, the casket with the relics rests on top of an open arched structure, so that pilgrims can reach up and touch or kiss it from beneath, without damaging the metal reliquary itself.

Sunday, July 06, 2025

The Octave of Ss Peter and Paul

Gregory DiPippo |

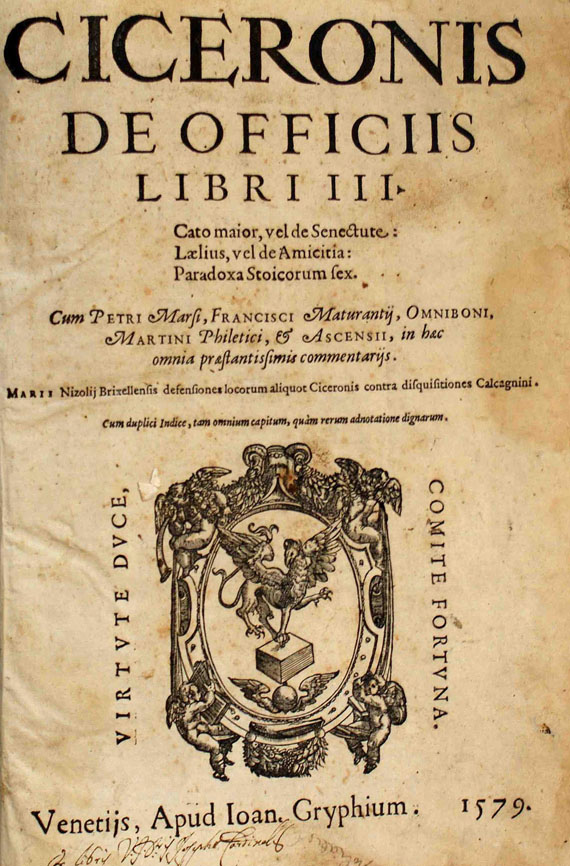

| (Public domain image from Wikimedia.) |

|

| Image from Pax inter Spinas, the printing house of the Monastère Saint-Benoît in Brignole, France. |

Friday, July 04, 2025

Interesting Saints on July 4th

Gregory DiPippo |

| The modern basilica of St Martin of Tours, built between 1886 and 1924 to replace a great medieval basilica which was destroyed during the Revolution. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by rene boulay, CC BY-SA 3.0.) |

|

| The tomb of St Martin in the crypt. |

|

| St Procopius, together with St Vicent Ferrer, on one of the decorative pillars of the Charles Bridge in Prague. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by ZP, CC BY-SA 2.5) |

|

| A page of the Reims Gospel book, with a picture of St Jerome in an illustrated letter. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

The Preface

Michael P. FoleyLost in Translation #130

The 1962 Missal contains twenty Prefaces (including the five so-called Gallican Prefaces added by Pope St. John XXIII in November of that year), but it may be more accurate to say with Abbé Claude Barthe that the Roman Rite has one Preface with twenty different options, just as there is one Roman Canon with different versions of the Communicantes and Hanc Igitur. [1]

Vere dignum et justum est, aequum et salutáre, nos tibi semper et ubíque gratias ágere, Dómine sancte, Pater omnípotens, ætérne Deus:

It is truly meet and just, right and salutary, that we should at all times and in all places, give thanks unto Thee, O holy Lord, Father almighty, everlasting God;

It is truly meet and just, right and salutary, that at all times, but more especially on this day [or in this season], we should extol your glory, Lord, when Christ our Pasch was sacrificed:

It is truly meet and just, right and salutary, to pray humbly to You, O Lord, eternal Shepherd, not to desert Your flock but to keep it in continual protection through Your blessed Apostles…

Posted Friday, July 04, 2025

Labels: Gallican Prefaces, Lost in Translation series, Michael Foley, Preface

Thursday, July 03, 2025

Photos from the CMAA Colloquium

Gregory DiPippoHere are some pictures of the liturgical celebrations held last week during the Church Music Association of America’s 35th Annual Sacred Music Colloquium, at the University of St. Thomas in Saint Paul, Minnesota

Wednesday, July 02, 2025

Saints Processus and Martinian

Gregory DiPippo |

| The north transept of St Peter’s Basilica |

Since the windows of St Peter’s Basilica are so high up, the marble walls are never exposed to direct sunlight for any great length of time, and generally remain cooler than the air. In the summertime, when Italy is often very hot and humid, a great deal of moisture comes into the building and condenses on the cooler marble. In the middle of the 18th century, it was realized that the paintings over the altars were being destroyed because they had a slick of condensation over them for several months of the year; there were therefore all taken down and replaced by mosaics. The original is now in the Painting Gallery of the Vatican Museums.

Valentin was an unabashed plagiarist of Caravaggio, in terms of both style and subject. One of the latter’s more prestigious commissions was a series of three paintings of the life of St Matthew in the Contarelli Chapel of the church of San Luigi dei Francesi. The angel whom Valentin shows here bringing the palm of victory to the martyrs is essentially a cross between the two angels painted by Caravaggio, one inspiring St Matthew in the writing of the Gospel, and the other bringing him the palm of martyrdom.

Dr. Kwasniewski’s Lectures in Spain (Seville, Cordoba, Toledo, Madrid, Segovia, Oviedo), July 18 to 25, 2025

Peter KwasniewskiInterview with Abbot of Fontgombault on the 1965 Missal, Questions of Reform, and the Current Situation in the Church

Peter KwasniewskiIn these times when much discussion is under way about the restoration of the pre-55 Roman Rite in view of the problematic aspects of the Pius XII Holy Week reform and the Bugninian aspects of the 1962 missal, it seems more than a curiosity to be reminded that the monastery of Fontgombault adheres to the 1965 interim missal, a sort of island that has nearly disappeared due to erosion from the oceans of controversy. Of interest to NLM readers will be this interview given by the abbot, Jean Pateau, to Lothar Rilinger in early May (translated from the German at kath.net). N.B. This article was scheduled long before a version of the same interview was posted at Rorate Caeli. Nevertheless, it won’t hurt to have the interview at both places. -PAK

Lothar Rilinger: You celebrate Mass in the old rite in your monastery. Do you believe that this type of celebration could jeopardize the unity of the faithful?

Abbot Jean Pateau OSB: First of all, I owe you a clarification. The monastery Mass in the abbey is not celebrated according to the 1962 Missal, known as the Vetus Ordo or old rite, but according to the 1965 Missal. Although this Missal is the result of the implementation of the reform demanded by the Council on December 4, 1963, but it remains closely linked to the 1962 missal and retains the Offertory and most of the gestures. In addition, we have decided to use the current [Novus Ordo] calendar for the Sanctoral. We have retained the old temporal calendar, which includes the season of Septuagesima, the octave of Pentecost, and the Ember Days, but we celebrate with the universal Church on the last Sunday of the year, Christ the King. All of this contributes to a rapprochement with the current 1969 Missal.

To answer your question about ecclesial unity more directly, I would like to recall that Benedict XVI, in his letter to the bishops on the occasion of the publication of the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, examined two fears that opposed the publication of this text:

- to diminish the authority of the Second Vatican Council and to cast doubt on the liturgical reform.

- causing unrest and even divisions in parish communities.

As regards the questioning of the authority of the Second Vatican Council, it should be recalled that, a few months after the publication of the Ordo Missae of 1965, the Archabbot of Beuron sent a copy of the post-conciliar edition of the Schott Missal to St. Paul VI. On May 28, 1966, Secretary of State Cardinal Cicognani sent a letter of thanks to the abbot on behalf of the pope, in which he stated: “The characteristic and essential feature of this new revised edition is that it represents the perfect crowning achievement of the Liturgical Constitution of the Council.”

As for the second point, I think we must guard against overly simplistic caricatures. There are places where there have been and still are divisions. There are also places where things are peaceful. Many would be surprised to learn that the majority of young people who decide to join so-called traditional communities are not young people who originally came from traditional communities. I myself am an example of this.

As for the young people who are drawn to traditional communities, they are very free in their liturgical practice and have long since left their home parishes.

Unity in the Church is not uniformity. An example of this is the Eastern Church.

Working toward unity does not mean working toward uniformity. I would even say that imposing uniformity is detrimental to unity. The question is how to work toward unity. This, it seems to me, was Benedict XVI's perspective.

Do believers in France want to attend Mass according to the old rite?

This question is difficult to answer, as the 1962 Missal is hardly used. What we can say, however, is that people who attend such celebrations have a sense of their contemplative dimension and are more focused on God. Many are willing to attend Masses celebrated according to this Missal from time to time and readily admit that it strengthens their faith.

Benedict XVI had already pointed out in the letter quoted above that, contrary to all expectations, “many people remained strongly attached to the old missal.” It is certain, and we can add that many people who get to know it develop an attachment to it.

Have you noticed that young believers in particular appreciate the old form of the missal and therefore go to church more often?

I can testify that a young religious who attended a Mass according to the Vetus Ordo asked me the following question, which was completely unexpected for me: “How is it possible that the Church hid this from us?” Others have expressed to me their desire to attend a Mass according to this Ordo.

Contact with the Mass in its old form can sometimes be surprising: “I came here because people speak badly of you!” “...Since then, this lady has persevered. Young people who remain steadfast in their religious practice today have high expectations. Drowned in a hyper-connected and noisy world where news is omnipresent, they appreciate the silence and sobriety of the texts in the Vetus Ordo. This more expressive, less intellectual character seems to me to be an advantage on a pastoral level.

It is said that believers who attend Mass according to the Vetus Ordo have a more regular practice. I believe this without hesitation. But I believe that the same is true for young people who are connected to a parish or a community.

Could the celebration according to the old rite also be a means of beginning a new evangelization?

To answer your question correctly, let us return to the 1965 Missal. Pierre Jounel dedicated a book to the rites of the Mass in 1965. In the introduction, he remarks: “When the Congregation for Rites published a new typical edition of the Roman Missal in 1962, no one had the impression that it was a real novelty. On the contrary, on March 7, 1965, priests and faithful discovered a new liturgy ...: the use of the vernacular, the celebration of the liturgy of the word outside the sanctuary, the fact that the celebrant no longer recited silently the texts proclaimed by a cleric or sung by the congregation.”

These reflections by a liturgist who witnessed the implementation of the reform, and the aforementioned judgment of Pope Paul VI, seem to me to lend the 1965 Missal a special authority and thus a specific missionary effectiveness. It is from this perspective that I would like to respond to you.

However, Jounel continues in his introduction by stating that “since March 7, certain problems raised by the liturgical reform have matured surprisingly quickly” – the imprimatur of the book dates from July 16, 1965! “In the celebration facing the people ... gestures dating back to the Middle Ages, such as the many altar kisses, the blessing of the oblates, the repeated genuflections, or even the quiet recitation of the canon, became a real burden for the priests, who until then had followed the rubrics in complete tranquility.”

This is precisely one of the criticisms of the current missal.

The connection between the celebration before the people and the fact that liturgical gestures suddenly become a burden is remarkable and seems to me to be evidence of a change in the mindset and spirit of these priests. Why have these gestures, which were previously taken for granted, become a burden? Is the priest ashamed? Does he find it ridiculous when the faithful see him doing what he has always done before God as a matter of course? Not everyone is able to ignore the stares.

Hasn't the same change of heart and soul taken place among the faithful? The undeniable striving for holiness among young people and many believers certainly deserves that liturgists hear this question and that we pause and reflect on it. The Apostolic Letter Desiderio desideravi has the merit of addressing this question.

Today, priests profess that they celebrate privately according to the Vetus Ordo. This nourishes their spiritual life. Even if the celebration of the Eucharist is not a matter of personal devotion, one cannot blame a priest for wanting to draw from it, for seeking substantial nourishment from it. In this sense, we can regret the abandonment of the orientation toward the Offertory and the drastic reduction of gestures.

Furthermore, I believe that evangelization could undoubtedly be strengthened by a rediscovery of the traditional orientation and gestures, which could very well be included in the current missal at will and which remind us that the Eucharist is the living memory of redemption, that there is Another who is made present, and that before this Other all go in adoration. The only subject of the liturgy is the mystical body of Jesus Christ, whose head and only high priest is Christ and whose members are the priests and faithful. A mutual enrichment of the two missals should be accompanied by a mystagogical catechesis in the spirit of the Church Fathers.

Do you believe that the Pope's motu proprio Traditionis Custodes represents a break with the theology of Benedict XVI/Ratzinger, who had actually made the celebration in the old rite possible?

It cannot be denied that Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI made the celebration according to the Vetus Ordo possible. Benedict XVI also paved the way for mutual influence between the two missals, first through his choice of terminology: ordinary form and extraordinary form of the same Roman rite, then through his invitation: “The new saints and some of the new prefaces can and must be inserted into the old Missal... In the celebration of Mass according to the Missal of Paul VI, this holiness, which attracts many people to the old rite, can be expressed more fully than has often been the case in the past.”

It is surprising that the Ecclesia Dei Commission took 13 years to introduce new saints and new prefaces into the old missal. Such a delay can only be explained by resistance that may have come from circles interested in retaining the old missal without any additions, as well as from liturgists who, after the death of the Vetus Ordo, were very opposed to updating this missal in a way that could prolong its use.

It seems important to me to reread Pope Benedict's letter to the bishops on the occasion of the publication of the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, which attests to its objectives:

- internal reconciliation within the Church

- that all who truly desire unity may have the possibility of remaining in this unity or of rediscovering it

Has the desired reconciliation taken place? It must be admitted that this is not the case. The Church, its members, bishops, priests, and faithful are suffering as a result, albeit for different reasons. Nevertheless, the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum undeniably calmed the situation. It ushered in a new era. However, I always believed that this era would not last unless real work was done in the direction desired by Benedict XVI. This work was not done.

Pope Francis' motu proprio Traditionis custodes has now changed the discipline. The situation has become more difficult for the faithful who are attached to the old missal. Some have turned to the Priestly Fraternity of St. Pius X. Others travel many miles to attend Mass according to the 1962 or 1965 missal or to receive a sacrament. In many places, tensions have flared up again. Jealousy is intensifying; misunderstandings are exacerbated, especially when the number of faithful attending Mass according to the Vetus Ordo increases and their average age is rather low. Anyone looking for political motives behind this success is mistaken. If the faithful go to these places, it is simply because they find what they are looking for there. Pope Francis' motu proprio ended the work desired by Pope Benedict to bring the two missals closer together.

In my opinion, there are two reasons for resuming this work. First of all, we cannot ignore the fact that the Second Vatican Council took place and that the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, was published, calling for a reform of the missal. The retention of the 1962 missal or the old Pontifical seems to me difficult to reconcile with this fact.

Furthermore, we cannot ignore the sharp decline in religious practice. Contrary to what is often claimed, the appeal of the old missal is not limited to certain European countries or the United States. The question is therefore justified as to whether a more expressive rite might not halt this decline to some extent. The reactions of the faithful and tourists who happen to attend a convent Mass in our monastery and are deeply moved lead me to believe that an enrichment of the 1969 Missal at will in terms of gestures, specifically the use of the Ordinary of the 1965 Missal with the Offertory and a celebration oriented towards it, would not be without fruit. Then it would be legitimate for all priests and Christians to benefit from it.

The 1969 Missal is a missal developed by learned liturgists, a missal “from above.” After more than 50 years, by drawing on the accumulated experience and feedback of a considerable number of faithful and priests, we can embark on a synodal path that for some is also a path of healing. The Church and her liturgy can only be enriched by this.

Pope Francis has invited us to be pilgrims of hope this year. I would like to believe that dialogue will be possible and that this dialogue will be beneficial for the whole Church. But genuine dialogue can only take place in trust, in truth, and in openness to what the other can teach me.

The Eucharist is the sacrament of God's love, in which Christ communicates his life. Too many believers, priests, and bishops are torn apart because of this sacrament, while Christ is present there with his body, his blood, his soul, and his divinity, begging for love.

|

| Daily private Masses at Fontgombault: a definitive sign that this monastery is not "on board" with the liturgical reform's general thrust |

Tuesday, July 01, 2025

Vespers of the Precious Blood

Gregory DiPippo |

| The high altar of the Jesuit church in Mindelheim, Germany, with the motif of Christ in the wine-press on the antependium. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by Thomas Mirtsch) |

Aña I that speak * justice, and am a defender unto saving. ibid.

Aña He was clothed * with a garment sprinkled with blood, and His name is called The Word of God. Apoc. 19, 13

Aña Wherefore then * is Thy apparel red, and thy garments as of them that tread in the wine-press? Isa. 63, 2

Aña I have trodden * the wine-press alone, and of the nations there was no man with Me. Isa. 63, 3

The passage from Isaiah is traditionally the first of two Old Testament readings on Spy Wednesday, when the station is held at St. Mary Major. In the middle of Holy Week, as the Church of Rome commemorates Christ’s Passion, and visits its principle sanctuary of the Mother of God, this Mass begins with a prophecy of the Incarnation, which took place in Mary’s sacred womb. The full reading is Isaiah 63, 1-7, preceded by a part of verse 62, 11.

Thus sayeth the Lord God: Tell the daughter of Sion: Behold thy Savior cometh: behold his reward is with him. 63, 1 Who is this that comes from Edom, with dyed garments from Bosra, this beautiful one in his robe, walking in the greatness of his strength? I, that speak justice, and am a defender to save. Why then is your apparel red, and your garments like theirs that tread in the winepress? I have trodden the winepress alone, and of the gentiles there is not a man with me: I have trampled on them in my indignation, and have trodden them down in my wrath, and their blood is sprinkled upon my garments, and I have stained all my apparel. etc.The Fathers of the Church understood this passage as a prophecy of the Passion of Christ, starting in the West with Tertullian.

The prophetic Spirit contemplates the Lord as if He were already on His way to His passion, clad in His fleshly nature; and as He was to suffer therein, He represents the bleeding condition of His flesh under the metaphor of garments dyed in red, as if reddened in the treading and crushing process of the wine-press, from which the laborers descend reddened with the wine-juice, like men stained in blood. (Adv. Marcionem 4, 40 ad fin.)This connection of these words with the Lord’s Passion is repeated in very similar terms by St. Cyprian (Ep. ad Caecilium 62), who always referred to Tertullian as “the Master”, despite his lapse into the Montanist heresy; and likewise, by Saints Cyril of Jerusalem (Catechesis 13, 27) and Gregory of Nazianzus (Oration 45, 25.)

The necessary premise of the Passion is, of course, the Incarnation, for Christ could not suffer without a human body. Indeed, ancient heretics who denied the Incarnation often did so in rejection of the idea that God Himself can suffer, which they held to be incompatible with the perfect and incorruptible nature of the divine. St. Ambrose was elected bishop of Milan in the year 374, after the see had been held by one such heretic, the Arian Auxentius, for twenty years. We therefore find him referring this same prophecy to the whole economy of salvation, culminating in the Ascension of Christ’s body into heaven, thus, in the treatise on the Mysteries (7, 36):

The angels, too, were in doubt when Christ arose; the powers of heaven were in doubt when they saw that flesh was ascending into heaven. Then they said: “Who is this King of glory?” And while some said “Lift up your gates, O princes, and be lifted up, you everlasting doors, and the King of glory shall come in.” In Isaiah, too, we find that the powers of heaven doubted and said: “Who is this that comes up from Edom, the redness of His garments is from Bosor, He who is glorious in white apparel?”In the next generation, St Eucherius of Lyon (ca. 380-450) is even more explicit: “The garment of the Son of God is sometimes understood to be His flesh, which is assumed by the divinity; of which garment of the flesh Isaiah prophesying says, ‘Who is this etc.’ ” (Formulas of Spiritual Understanding, chapter 1).

|

| The Risen Christ and the Mystical Winepress, by Marco dal Pino, often called Marco da Siena, 1525-1588 ca. Both of the figures of Christ in this painting show very markedly the influence of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment. |

John also in the Apocalypse bears witness that he saw these things: “I saw heaven opened, and behold a white horse; and he that sat upon him was called faithful and true, and with justice doth he judge and fight. And his eyes were as a flame of fire, and on his head were many diadems, and he had a name written, which no man knoweth but himself. And he was clothed with a garment sprinkled with blood; and his name is called, the Word of God. And the armies that are in heaven followed him on white horses, clothed in fine linen, white and clean. And out of his mouth proceedeth a sharp two edged sword; that with it he may strike the nations.” The Lord and Savior sat upon a red horse, taking on a human body; to whom it is said “Why are thy garments red?” and “Who is this that cometh from Edom, his garments bloodied from Bozrah?” St Jerome presumes his reader’s familiarity with the exegetic tradition that the “garment” and “bloodied vestment” in Isaiah 63 refer to the Incarnation. He does even need to finish the thought by pointing out that both passages refer to a “wine-press” as a symbol of the instrument of Christ’s sufferings.

|

| The Rider on the White Horse, Apocalypse 19, from the Bamberg Apocalypse, 1000-1020 A.D. The lower part shows the angel calling to the birds of prey in verse 17 of the same chapter. |

Now, in John’s vision, the Word of God as He rides on the white horse is not naked: He is clothed with a garment sprinkled with blood, for the Word who was made flesh and therefore died is surrounded with marks of the fact that His blood was poured out upon the earth, when the soldier pierced His side. For of that passion, even should it be our lot some day to come to that highest and supreme contemplation of the Logos, we shall not lose all memory, nor shall we forget the truth that our admission (into heaven) was brought about by His sojourning in our body. (Commentary on the Gospel of John, Book II.4)

Pilgrimage Following in the Footsteps of Newman - London, Oxford, Birmingham and Rome; October 2025

David ClaytonThis October marks the 180th anniversary of the conversion to Catholicism of St. John Henry Newman. Here is an opportunity to mark the occasion with a pilgrimage led by Father Peter Stravinskas, editor of The Catholic Response and president of the Catholic Education Foundation, and Dr. Robert Royal, editor of The Catholic Thing. It runs from October 5th to 19th, beginning in London, where Newman was born, and ending in Rome. During the English leg of the pilgrimage, in addition to London, there will be visits to Littlemore near Oxford, the University Church in Oxford, Maryvale, and the Birmingham Oratory.

Single occupancy: +$2,300.

www.The-Catholic-Journey.com/1025Newman

Phone: (215) 327-5754

Email: fstravinskas@hotmail.com

Phone: (201) 523 - 6148

Email: info@the-catholic-journey.com

|

| The interior of the Birmingham Oratory |

Monday, June 30, 2025

Another Update from the Palestrina500 Festival in Grand Rapids

Gregory DiPippoOn Friday, April 25th, the Friday of Easter Week, Sacred Heart of Jesus Parish in Grand Rapids, Michigan, welcomed the world-famous Tallis Scholars to sing a choral meditation and Mass for the parish’s year-long Palestrina500 festival. The choral meditation consisted of:

- Palestrina: Missa “ut re mi fa sol la”

- Palestrina: Laudate pueri Dominum

- Lassus: Media vita in morte sumus

- Lassus: Timor et Tremor

- Palestrina: Tu es Petrus

- Mendelssohn: Am Himmelfahrtstage

- Jonathan Dove: Into Thy Hands

- Manuel de Sumaya: Adjuva nos Deus

- Blake Henson: My Flight for Heaven

- Palestrina: Assumpta est Maria

- David Bednall: Assumpta est Maria

- Stephan Paulus: Splendid Jewell

Sunday, June 29, 2025

The Feast of Ss Peter and Paul 2025

Gregory DiPippo |

| Ss Peter and Paul, with Ss John the Evanglist and Zeno; the left panel of the polyptych of San Zeno by Andrea Mantegna, 1457-60. |

Saturday, June 28, 2025

The Vigil of Ss Peter and Paul

Gregory DiPippo |

| The Crucifixion of St Peter, depicted in the Papal Chapel known as the Sancta Sanctorum at the Lateran Basilica in Rome, ca. 1280. |