Lost in Translation #118

At the middle of the altar, the priest offers the new mixture of water and wine. Holding the chalice at about eye-level and raising his eyes to the altar cross, he says the prayer Offerimus tibi. When he is finished, he makes the sign of the cross with the chalice and places it on the corporal. The prayer is:

Offérimus tibi, Dómine, cálicem salutáris, tuam deprecantes clementiam: ut in conspectu divínae majestátis tuae, pro nostra et totíus mundi salúte, cum odóre suavitátis ascendat. Amen.Which I translate as:

We offer unto thee, O Lord, the chalice of salvation, entreating Thy clemency, that it may ascend in the sight of Thy divine majesty, as an odor of sweetness, for our salvation, and for that of the whole world. Amen.Whereas the Suscipe Sancte Pater enters the Roman Rite through the Gallican, the Offerimus tibi has a provenance even further West, the Mozarabic in Spain.

The grammatical number of the speaker has changed. In the Suscipe Sancte Pater, the priest uses the first person singular to say that he is offering the host for his sins, etc. Here, instead of “I” he says, “We offer.” While some speculate that this is the “royal we,” the more obvious explanation is that at a Solemn High Mass the deacon, who helps mix the water and wine, now touches the base of the chalice with his right hand as the priest elevates it and joins the priest in reciting the Offerimus. For although the deacon in no way confects the Eucharist, he has a special guardianship of the chalice: in the days when Holy Communion was offered under both kinds, it was the deacon alone who distributed the Precious Blood with the chalice and a golden straw (suspended over the communicant’s mouth) called a fistula.

That the Offerimus keeps the first-person plural even when the priest celebrates Mass without a deacon’s assistance (e.g., at a Missa cantata and Low Mass) is a reminder that whatever Mass is being celebrated, the normative mode of celebration in the Roman Rite is a Solemn High Mass, and that all other forms are concessions that are derived from it.

The priest refers to the chalice containing water and unconsecrated wine as the “chalice of salvation”—yet another instance of “dramatic misplacement” or anticipation of the consecration. But the diction suggests an additional possibility. While the Latin salvatio is the predominantly Christian terms for spiritual salvation or deliverance [1], the word used here for “salvation” (salus) can also mean “safe and sound,” “health,” or “a wish for one’s welfare.” [2] The prayer thus contains a certain ambivalence between the spiritual and the physical, one that alludes to the ambiance of wine-drinking, as when one raises a glass and, toasting to someone’s health, says, Salut!

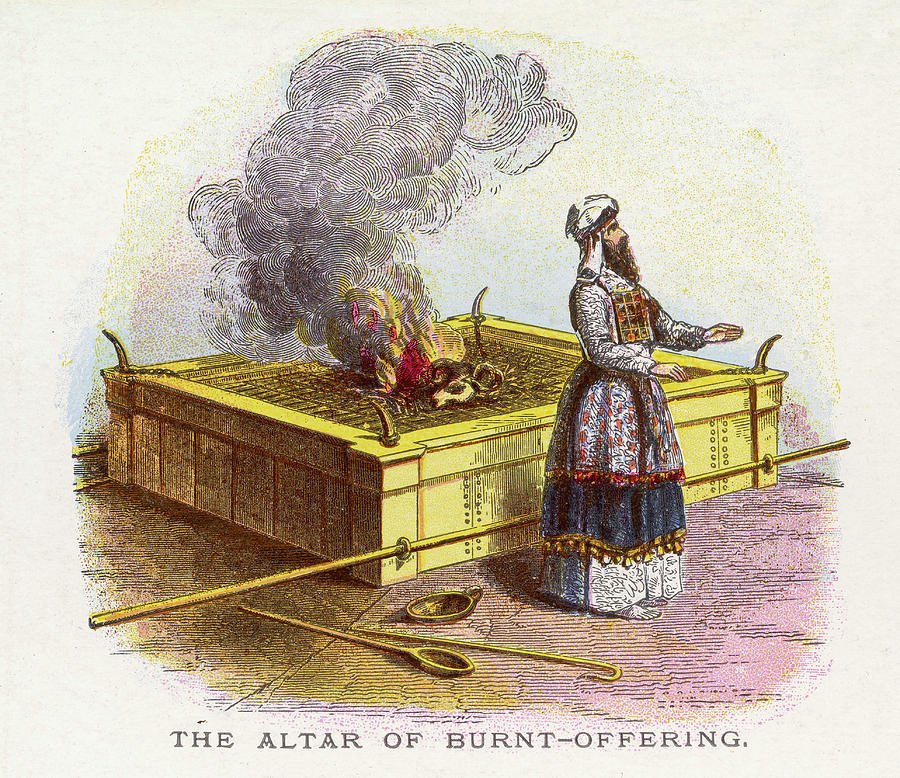

Another nod to the natural qualities of wine is the petition that the offering ascend to God as an “odor of sweetness,” for wine has a bouquet or smell that is appreciated along with its taste. The phrase “odor of sweetness” also looks back to the Old Testament burnt offerings, where God is “fed” when He smells with approval the smoke of the victim being consumed by fire. (See Genesis 8, 21, Exodus 29, 25) The wording is also an echo of Ecclesiasticus 35, 8-9: “The oblation of the just maketh the altar fat, and is an odour of sweetness in the sight of (in conspectu) the most High. The sacrifice of the just is acceptable, and the Lord will not forget the memorial thereof.” Further, it is an allusion to Ephesians 5, 2: “And walk in love, as Christ also hath loved us, and hath delivered himself for us, an oblation and a sacrifice to God for an odour of sweetness.” For this wine is about to become Christ Himself thanks to the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

Finally, this glass is raised—or rather, this chalice is offered—for the health or salvation of not only the offering priest and deacon, and not only, as with the Suscipe Sancte Pater, all Christians living and deceased, but the whole world as well: that is, for the conversion of sinners. The Mass is the portal through which sanctifying grace enters our fallen world.

Notes

[1] “Salvatio, -onis, f.,” Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary, 1623.

[2] “Salus, -utis,” Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary, 1621-1622.