At a Solemn High Mass, after the deacon finishes the Gospel, the subdeacon takes the Gospel book to the priest, who kisses it and says quietly: Per evangelica dicta deleantur nostra delicta. At a Missa cantata or Low Mass, the priest takes the Missal in his hands and kisses it, saying the same prayer.

Per evangelica dicta deleantur nostra delicta is in the new Missal as well. In the 2011 English edition, it is translated as:

Through the words of the Gospel may our sins be wiped away. [1]

The earlier ICEL translation had changed the sense of the text with “May the words of the Gospel wipe away our sins.” [2] The passive verb (deleantur) was changed to active, and the words themselves became the direct agents that wipe away sins rather than the instruments with which God wipes away sins.

All of the preconciliar hand Missals that I consulted had a translation similar to the 2011 English translation:

By the words of the Gospel may our sins be blotted out. [3]

By the words of the holy Gospel may our sins be blotted out. [4]

May our sins be blotted out by the words of the Gospel. [5]

By the words of the Gospel may our sins be taken away. [6]

Through the words of our Gospel may our sins be blotted out. [7]What all these translations have in common is their treatment of dicta as a noun. Dicta can indeed be a noun (the accusative plural of dictum,i), but it can also be a past participle of the verb dico, dicere, in which in case it can be translated:

By virtue of these evangelical passages having being said, may our sins be blotted out.

I do not think it is a mistake to treat dicta as a noun so long as its “participled” meaning is also kept in mind, for it seems to me that the prayer is asking for the action of liturgically proclaiming the Gospel to have the effect of forgiving sins. Even though dicta means “words,” I think it is better to translate it as “sayings” (another one of its meanings) in order to highlight the speaking or acting emphasis of the prayer. The problem with “words” is that words can appear on pages and stay there. “Sayings,” on the other hand, even when they are written down, cannot etymologically escape their relationship to speaking.

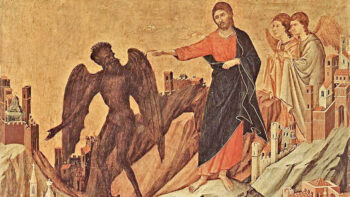

In any event, it is an astonishing prayer, for it connects the mere hearing of the Gospel at Mass with absolution; it is asking for the Gospel proclamation to function as a sacramental, even though we have had several already, from the Asperges to the Confiteor to the Prayers Ascending the Altar. But the prayer is grounded in the Bible. In Luke’s Gospel (6, 18), we read how those who were troubled by unclean spirits and who heard Jesus speak were cured. And we truly hear Jesus speak when His Gospels are proclaimed.

In other words, the liturgical proclamation of the Gospel is far more than a Sunday Bible School lesson; it is a re-presencing of the Son of God through His words, and it is therefore more powerful than when the Bible is read extra-liturgically, as in a classroom or even when it is read again in the vernacular during the liturgical interlude comprised of the homily. (It is for this reason that some TLM communities do not stand for the vernacular re-reading of the Gospel or use the liturgical apparatus for the Gospel; the non-liturgical re-reading does not put us in the presence of Christ as does the liturgical proclamation.)

One of the interesting implications of this theology of liturgical proclamation, incidentally, is that it reveals a problem with the custom in some Novus Ordo parishes of ushering children away during the Liturgy of the Word for their own Bible study. The goal of increasing biblical literacy in the young is admirable, but they are missing a graced moment.

Good, but not the same

We end with Fr. Nicholas Gihr’s commentary, which is worth quoting at length:

If the Gospel is taken into the heart and preserved therein, with all that esteem and submission, love and joy, which the kissing of the book denotes, then is the Gospel also able “to blot out our sins.” It is self-evident that no such power of effacing sin may be ascribed to the words of the Gospel, as is peculiar to the forms of the Sacraments of Baptism and Penance: they are only a kind of Sacramental in a more general sense and have, therefore, assuredly a great power of awakening and promoting that disposition of soul by which venial sins are effaced, or which prepares for and renders one worthy of receiving the Sacraments. The word of God, which is accompanied by the interior working of grace, exercises a redeeming, healing and sanctifying influence on man when he is properly disposed, by exciting faith, hope and charity, fear and contrition, conversion and amendment of life. It is not only a powerful means of clearing the soul of the excrescence of sin and imperfection, but it possesses, moreover, other beneficial effects besides. “Are not My words as a fire, saith the Lord, and as a hammer that breaketh the rock in pieces?” (Jer. 23, 29.) Yea, the words of the Lord are spirit and life: they are powerful, two-edged, penetrating. When Christ on the road to Emmaus “opened” the meaning to the two disciples of “the Scriptures, their hearts burned within them.” The word of God has a marvellous power for enlightening the eyes, for imparting wisdom to the lowly and the humble, for rejoicing the heart and refreshing the soul. In like manner, may the living and quickening word of God, which abides forever, impart to us “salvation and protection,” may it purify, consecrate and sanctify our souls ever more and more. For “the Gospel is the power of God unto salvation to every one that believeth.” (Rom. 1, 16). [8]

Notes

[1] 2011 Roman Missal, 9.

[2] 1985 Sacramentary, 365.

[3] Baronius Press, 919; Catholic Publications Press, 38; Cabrol, 26.

[4] Stedman, 41.

[5] Lasance, 765.

[6] Saint Joseph, 554.

[7] 1959 St. Andrew, 803.

[8] Gihr, 482-83.