Govert Flinck, Angels Announcing the Birth of Christ to the Shepherds, 1639

Lost in Translation #100

The Gloria in excelsis was translated from Greek into Latin, possibly by St. Hilary of Poitiers (310 ca. - 367). We are happy to honor this attribution while also entertaining the likelihood of a later redactor.

The first verse of the Gloria is:Gloria in excelsis Deo,et in terra pax homínibus bonae voluntátis.

Which I translate as:

Glory to God in the highest places,And on earth, peace to men of good will.

The verse is taken from Luke 2, 13-14, which according to the Vulgate is:

Et subito facta est cum angelo multitudo militiae caelestis laudantium Deum, et dicentium: Gloria in altissimis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.

Which the Douay-Rheims translates as:

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly army, praising God, and saying: “Glory to God in the highest; and on earth peace to men of good will.”

Word Order and Implied Verb

The first peculiarity is the syntax and the lack of an explicit verb in both the original Greek and in the Latin translation. As one of my teachers used to say, word order in Greek and Latin does not matter--until it does. There is a difference between saying that to God belongs the glory that is in the high places and saying that glory belongs to God, who is in the high places. Most interpretations favor the latter.

And because the verb “to be” in this verse is only implied, we do not know if the statement is in the indicative or subjunctive. Are we singing that all glory is God’s, or that all glory should be given to God? I believe that context supports the latter interpretation, but grammatically both are equally valid.

The Good Place, or the Good Places?

Another peculiarity in the original Greek is the diction. Why did the Evangelist use the plural rather than the singular for God’s location? The Greek ὑψίστοι (hypsistoi) appears in the Nativity narrative of Luke 2, 14, and in the Palm Sunday entrance into Jerusalem narratives of Matthew 21, 9, Mark 11, 10, and Luke 19, 38.

English translations usually have “Glory to God in the highest,” and they are not wrong, but the Greek (and Latin) are in the plural: “Glory to God in the highest places.” What is the difference? There may not be a logical but a psychological distinction. At least to my mind, the singular suggests a fixed place, and fixed places are more comprehensible and therefore more reassuring. Robert Browning seems to agree in his poem “Pippa’s Song”:

The year’s at the spring,And day’s at the morn;Morning’s at seven;The hill-side’s dew-pearl’d;The lark’s on the wing;The snail’s on the thorn;God’s in His heaven—All’s right with the world!

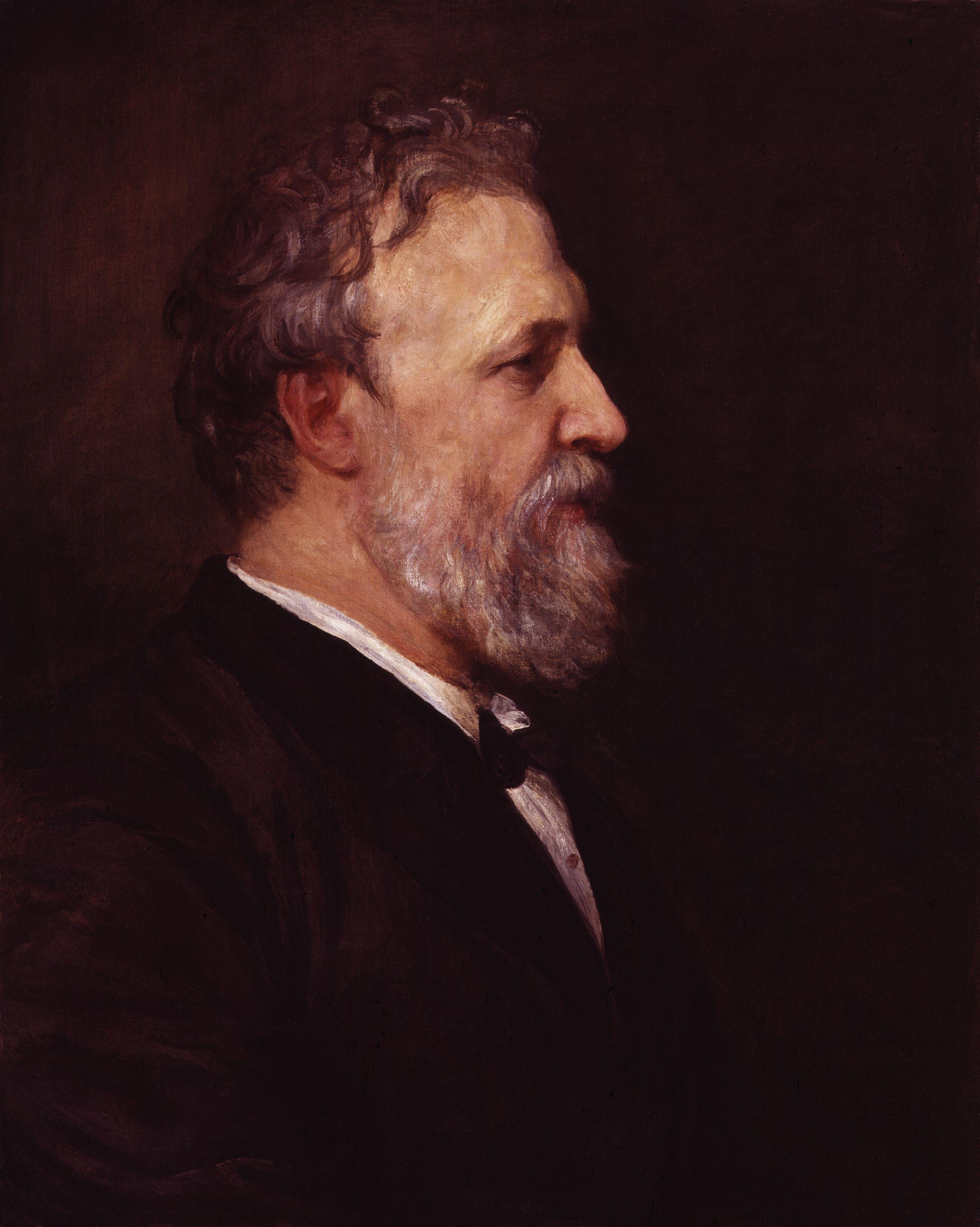

Robert Browning

“God’s in His heaven,” and “all’s right with the world.” For Browning, Heaven is a well-bounded place, a center of stability from which God regulates or at least sits atop the world. But the term “highest places” is more amorphous, and perhaps a little more unsettling. In this case, God does not come from a center of stability but from a mysterious, numinous realm—or realms—which are not easily circumscribed. God comes from God knows where; He is the Other who dwells in the nebulous regions of otherhood. We shall return to this topic when we examine the Credo.

High from Above or from Below?

As for the Latin translation, one may wonder about the choice of excelsis rather than altissimis for hypsistois. There is a Vetus Latina manuscript [1] that translates Luke 2, 14 as Gloria in excelsis Deo, and there may be one that translates the verse as Gloria in altissimis Deo. In any event, St. Jerome’s Gospels, which were published twenty years after St. Hilary passed away, has altissimis for hypsistois in Luke 2, 14 and in Matthew 21, 9 (the entrance into Jerusalem), while excelsis is the Vulgate word for the Jerusalem entrance in Mark 11, 10 and Luke 19, 38.

It should be borne in mind that St. Jerome did not translate the Gospels afresh from the original languages, but edited the prevailing Vetus Latina translations, which were uneven in quality and often had multiple variations for any given verse. He often kept divergent terms that he personally would have preferred to regularize. For example, in the Gospel texts that he inherited, “high priest” (ἀρχιερεὺς, archiereus) is rendered princeps sacerdotum in Matthew 26, 62 and Luke 22, 50, summus sacerdos in Mark 14, 53, and pontifex in John 11, 49. Whatever his personal druthers, Jerome let them be.

St Jerome presents the Gospels to Pope St Damasus I

Again logically, there is little difference between altissimi and excelsi, for both are in the plural and both signify height or loftiness. If we can ascribe any divine providence to the appearance of excelsis in the Great Doxology, it might be this. In classical Latin, altissimus literally designates altitude, height, or depth, while excelsus (ex-cello) is etymologically related to excellence. With excelsis, God is not far away in a distant galaxy but in an elevated position of outstanding superiority. It is true that altissimus can also mean noble or elevated, but the word also suggests being “seen from below upwards.” [2] Excelsus, on the other hand, can mean seeing from the perspective of what is above or at least seeing on the same level.

The Angelic Hymn, then, begins with a bird’s eye—or rather, an Angel’s eye—viewpoint that looks at God’s glory not from below but from the heights. It thus forms a more striking contrast between the mysterious realms of God and the earth, where dwell the poor, well-intentioned humans that are the subject of the rest of the verse and to whom we will turn next week.

NoteS

[1] The Vetus Latina (also known as the Itala or Old Italic) is the collection of early Latin translations of the Bible, a collection that admitted of numerous manuscript variations. In A.D. 382, Pope Damasus I commissioned St. Jerome to revise the Vetus Latina Gospels.

[2] “Altus, a, um,” under “Alo,” A, Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1879), p. 95, column B.