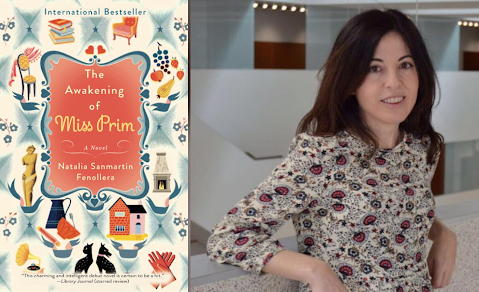

In 2013, a novel by a hitherto unknown Spanish writer was published, and, to the surprise of many, became an international bestseller: “The Awakening of Miss Prim,” written by Natalia Sanmartín Fenollera. I recently came across an interview that was done with Ms. Sanmartín in December of 2021 with the journalist José María Sánchez Galera at the website of El Debate (Spanish original here). Its abundant interest made me wish to share it with NLM readers.—PAK

Few people have not heard of The Awakening of Miss Prim (2013). And those who have read this novel are surprised that its author, the Pontevedra-born Natalia Sanmartín Fenollera, has not made a literary career. She has published another book, A Christmas Carol for Le Barroux, which tells how a child loses his mother and asks God if the story of Bethlehem is true. Sanmartín does not live by producing articles full of scholastic theories, but works in the economic press. Her perspective is marked by various influences: from the Fathers of the Church, St. John Henry Newman, and British intellectuals such as Lewis, Knox, and Chesterton, to John Senior (in fact, thanks to her, La restauración de la cultura cristiana has been published in Spain). All this tradition helps to understand the devotion and deep respect she feels for Benedictine spirituality and carefully celebrated liturgy, as well as her literary passion and her interest in assiduous reading of the Bible. That is why she comments, “The depth of the liturgy and of the divine office teaches us that the tender God is also the warrior God.”

Galera: In A Christmas Carol for Le Barroux and The Awakening of Miss Prim, you speak to us, in a certain way, of a kind of need to get out of the world or the noise. To what extent?

Sanmartín: It’s true that this idea is present in both stories, although in the Christmas story it’s not so much a geographical distance as a spiritual one. But I wouldn’t say that getting away from the world is an absolute necessity, a kind of imperative, and it seems to me that there is a certain misunderstanding in some of the discussions there have been about this question.

All decisions that have to do with one’s state of life are prudential; there is no instruction manual. It would be simpler if there were, but there is not. Any debate about whether a Christian is right or wrong to try to lead a life away from the world must take this into account, that it is a question of prudence: there will be those who believe they should and can do it, there will be those who cannot, even if it seems a good way, and there will be those who conclude that their place is elsewhere.

When we turn to Scripture to defend that the Christian has to be in the midst of the world, we usually quote the passage about the salt of the earth, but the problem with using Scripture to argue about this type of question is that Scripture is very broad and very rich, and we cannot take only a piece of it. The Gospel also says to shake the dust off our sandals wherever the word of God is not received. The Church has always taught that the Christian should have a healthy distance from the world—live in it, but not belong to it, and this is valid whether one lives in the middle of a big city or at a monastery. There are Christians in the world and Christians far from it, some on the ramparts and others in the rearguard. It has always been like that and I think that is the right way to look at this matter. But to both, the Church says the same thing: you are children of God, and that means that you live in this world, but you do not belong to it.

There is also a certain lack of realism in those who say that “distancing oneself from the world to protect the Faith is a mistake.”

Galera: There are those who consider the “beatus ille” [Happy that man who is free from business cares…] to be nothing more than a literary cliché.

Sanmartín: That may be partly true, but, formulated as Horace did, I think it is much more than that. It is also a warning about the dangers of the lust for power and government, about the arrogance of man who concentrates on power. I agree that one can idealize the quiet life and even more the rural life, but one can also idealize life in the big cities, professional success, family, marriage, and even religious life. And in part, it is good that this is so; this idealization has a function, because, if from the beginning one could contemplate the difficulties of a path in all their rawness, one would never choose it.

But it seems to me that there is also a certain lack of realism in those who claim that distancing oneself from the world in order to protect one’s Faith is a mistake or a desertion. Many of these criticisms seem to forget the brutal secularization that has flooded the world, including the Christian world—a secularization that has entered the Church and has broken the chain of transmission of faith between generations. It is very Christian to aspire to be salt in a land hostile to God, but perhaps we must first ask ourselves what is happening within our own walls, what is happening to our own faith, that of our children or grandchildren—to what extent what we believe and what we transmit and what they have received corresponds to the faith of the apostles… or is it rather what Lewis called “watered-down Christianity”?

And finally, it seems to me that some things are indisputable: the fruits of the retreat to the desert and of Christian contemplation have always been great and profound. You have only to look at the history of the Church to see that.

Galera: Pablo d’Ors—who in an interview with me said “turning off the cell phone is at least 50% of the spiritual journey”—recently said that silence, more than the absence of noise, is the absence of ego. But is that enough for silence to be a door to listen to God?

Sanmartín: The absence of ego is not just any old thing; it is an enormous fruit of holiness. The desert fathers always mention this—humility and silence—and they also speak of waiting, of patience. When a young person came to them and asked them how to seek God in prayer, they did not answer with methods or exercises; they taught that the initiative is always God’s, that the grace that allows us to open our hearts and listen comes also from God, and that we are all, so to speak, on the outer side of the door, like beggars before Paradise. That is our real position, with our weaknesses and falls, as being what we are: a wounded race that one day shouts hosanna and another day demands crucifixion. Scripture tells us beautiful and mysterious things, such as that God speaks as a whisper in the breeze, but it also says that his voice shatters the cedars of Lebanon. I am very impressed by a sentence of the desert fathers that recommends the young monk to pray “alone before the Alone.”

Galera: Would the criterion for all the above—silence, isolation, flight from the world, etc.—be God?

Sanmartín: The criterion for a Christian must be the search for God’s will, which is not an easy thing. I am not the “providentialist” type, the type that easily sees in everything a sign of what God wants or does not want; it seems to me that trying to fulfill the commandments, getting up every time one falls down and worshiping God in the highest and holiest way possible, is the way to do His will; everything else is very difficult to know. Newman has a beautiful poem in which he tells God that he does not need Him to show him the horizon, that it’s enough that He guide him to be able to take one more step until the night ends and the morning brings the smile of the angels.

Galera: We speak little today in the Church about the Last Things (Death, Judgment, Heaven, Purgatory, Hell)...

Sanmartín: Yes, it is true that little or practically nothing is preached, that the homilies do not speak of the fact that life on earth is a warfare, as Job says, and that God loves us but He also takes our freedom seriously. But I think it is not only a question of preaching, but also of the depth of the liturgy and of the divine office, which teaches us that the tender God who tried to gather Israel as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings is also the warrior God of the Armies, and who leads us, now in Advent, to a time of penitence before joy. The Church teaches that we believe what we pray. If this is true, consider that a bimillenial liturgy says that death and nature “will be astonished when all creation rises to answer to its Judge,” and makes us say to God: “You who absolved Magdalene and heard the thief’s plea, grant me hope too” (the Dies Irae), while another liturgy [the Novus Ordo] describes in one of its prefaces a “Sunday without sunset” in which “the whole of humanity will enter into rest.”

Galera: A question that we’ve already posed recently to Rémi Brague and Fabrice Hadjadj: Is the Christian world retreating in the face of the secular wave of postmodernity? Are we entering a post-Christian era? Will the Church be confined to ghettos or catacombs?

Sanmartín: I believe that we are already in a post-Christian era, that we live in the midst of a vineyard that has been assaulted from without and from within—a devastated vineyard, as Dietrich Von Hildebrand called it in the book he wrote in 1973. But it is not just any vineyard, for it is protected by an unbreakable promise, even if we do not know how that promise will be kept or whether the result will ultimately resemble what we know now. The Church began small and we are taught that it will end up small again, but it will be recognized because it will preserve what it has kept from the beginning: the faith of the apostles, the sacredness of the liturgy, and the memory of the saints and martyrs.

Visit Dr. Kwasniewski’s Substack “Tradition & Sanity”; personal site; composer site; publishing house Os Justi Press and YouTube, SoundCloud, and Spotify pages.