The acts of St Catherine of Alexandria tell us that she was a noblewoman of immense learning in all the sciences, who at the age of eighteen went to the emperor Maximin Daia (305-312) to reprove him for his persecution of the Church, denouncing the worship of the false gods of the pagans. Unable to respond to her himself, Maximin had her imprisoned, and then brought a group of fifty philosophers to explain to her the folly of Christianity; all of these she converted to the Faith, for which they were put to death. Catherine was returned to prison, where she was visited by the empress and a captain of the emperor’s troops named Porphyry, both of whom were also converted, and soon after martyred. Catherine was then condemned to die by the famous spiked wheel which has long been known as her emblem, but which broke apart on touching her; like so many Saints whom Nature itself and the persecutors’ devices refused to harm, she was then beheaded. As the traditional Collect of her feast states, her body was carried by Angels to Mount Sinai, where first a church, and later the famous monastery were built in her honor.

|

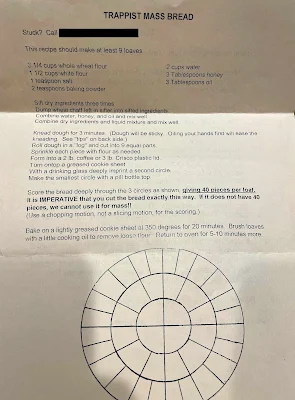

An icon of the Presentation of Mary, with St Catherine on the far left. (Greek, 18th century). In the Byzantine Rite, the Entrance of the Virgin in the Temple is one of the twelve Great Feasts, most of which are kept with both a Forefeast and Afterfeast, broadly the equivalent of a vigil and octave in the traditional Roman Rite. Afterfeasts vary in length, and those of the Virgin’s Presentation and Nativity are the shortest, only four days, the final day being known as the Leave-taking; the Leavetaking of the Presentation therefore coincides with St Catherine’s feast day. ( Photo from Wikimedia Commons by shakko.) |

She became one of the most popular Saints of the High Middle Ages beginning in the 11th century, when some of her relics were brought to the French city of Rouen. Innumerable churches and chapels were dedicated to her, she appears in an extraordinary number of paintings and statues, and her feast day was kept in many places as a holy day of obligation. She has long been honored as a Patron Saint of philosophers and theologians, orators and preachers, (and hence especially by the Dominicans, who kept her feast with an octave until the early 20th century,) but also of women in religious life, students of every sort, millers and wheelwrights. In France, her prestige was very much enhanced by the fact that she was one of the Saints who spoke to St Joan of Arc. She is honored in the Byzantine Rite with the title “Great Martyr”, and named in the preparation rite of the Divine Liturgy; in the Ambrosian Rite,

her name was even added to the Canon of the Mass in the later 15th century.

It is painful to relate that no aspect of the life of St Catherine as given in her acts can be considered historically trustworthy. Just to give one of many possible examples, she is named as the “daughter of a king named Costus”, even though Egypt in the early fourth century was a province of the Roman Empire, and had had no king for over three-hundred years. There is no mention of her in the wealth of Egyptian Christian literature for several centuries after her death, or in the various accounts of pilgrims to the monastery on Mt Sinai, which was not originally named for her.

By the time

the Roman Breviary was revised after the Council of Trent, scholars had long known that many of the well-known and loved stories of the Saints were not historically reliable. Thus we find several of the Virgin Martyrs who were very popular in the Middle Ages, such as Ss Barbara, Margaret of Antioch and

Ss Ursula and Companions, reduced from full offices of nine readings in the Roman Breviary of 1529 to a mere commemoration in the Breviary of St Pius V. Even Ss Cecilia and

Agatha, who are named in the Canon of the Mass, were originally kept at the second of three grades; only Ss

Agnes, the Roman martyr par excellence among women, Lucy (a rather random choice), and Catherine of Alexandria were kept at the highest grade.

|

Virgo inter Virgines (The Virgin Mary among the other holy virgins) by the anonymous Netherlandish painter known as the Master of the St Lucy Legend, ca. 1490. The holy Virgins are Ss Apollonia, Ursula, Lucy, Dorothy, Catherine (receiving a ring from the baby Jesus; her red cloak is covered with her symbol, the wheel), Mary Magdalene, Barbara, Agnes, Margaret, Agatha and Cunera, patron of the Rhenen area near Utrecht, said be one of the 11,000 companions of St Ursula. (Click image to enlarge; click here for a complete explanation of the icongraphy.) |

The Breviary of St Pius V, first published in 1568, was revised in the last decade of the same century, and a new edition published in 1602. Pope Clement VIII had entrusted the task of correcting the Saints’ lives to the great Cardinal Cesare Baronius, also the principal editor of the first Tridentine edition of the Martyrology. Among Baronius’ collaborators was St Robert Bellarmine, one of the most learned men of his age, who is supposed to have said in regard to St Catherine, “I wish I could believe that she existed.” In his

History of the Roman Breviary, Mons. Pierre Batiffol notes (p. 216) that Baronius often refused, against St Robert’s advice, to alter some of the popular legends, despite the historical problems associated with them; and that he noted of St Catherine specifically, “Her history contains many things which are repugnant to the truth.” Nevertheless, her Office was left unaltered, and remained in the same form until

the Breviary revision of 1960.

It was certainly a goal of the Tridentine reform of the Breviary to remove from the Church’s public prayer anything that might offer the Protestants a pretext for attack or ridicule. (

Baronius was well aware of this problem, and also produced a massive history of the Church, covering the first 12 centuries, in response to Protestant controversialists.) The question therefore arises as to why a Saint whose life was subject to serious doubts, even on the part of the very revisers of the Breviary, was not merely included in it, but celebrated in one of its most prominent feasts.

In part, we may simply say that scholars must at times take their lesson from the devotion of the people, and accept what they may perhaps not understand. (It is interesting to note in this regard that St Catherine was abolished in the Novus Ordo, but restored to the general calendar by Pope St John Paul II.) But there are three aspects of the story of St Catherine that are particularly significant to the Counter-Reformation, which certainly contributed to the preservation of devotion to her.

The first is her role as the Patron Saint of philosophers, which comes, of course, from the story told above of her converting the fifty men sent to dissuade her of her Christian faith.

The second is her role as patron of women in religious life. This arises from the story that Maximin offered to take her on as a second wife or mistress, and even honor her as a goddess, if she would renounce the Faith. To this Catherine replied, “It is a crime even to think of such things. Christ has taken me to Himself as a bride; I have joined myself to Him as a bride in an indissoluble bond.” Other virgin martyrs like Ss Agnes and Agatha also speak of themselves in similar terms, but for whatever reason, it was seen as especially important in Catherine’s case. Therefore, she is very often represented, both before and after the Counter-Reformation, receiving a wedding ring from the infant Christ as He is held by His Mother, joined to him in a mystical marriage, although this is not specifically said in the text of her acts commonly read in medieval breviaries, nor in the Golden Legend.

|

| The Mystical Marriage of St Catherine, by Guercino, 1620 |

The third reason has to do with her place among

the Fourteen Holy Helpers. In the 1499 Missal of Bamberg, the Collect of a Votive Mass in their honor reads as follows:

Almighty and merciful God, who didst adorn Thy Saints George, Blase, Erasmus, Pantaleon, Vitus, Christopher, Denis, Cyriacus, Acacius, Eustace, Giles, Margaret, Barbara and Catherine with special privileges above all others, so that all who in their necessities implore their help, according to the grace of Thy promise, may attain the salutary effect of their pleading: grant us, we beseech Thee, forgiveness of our sins, and with their merits interceding, deliver us from all adversities, and kindly hear our prayers.

The words “according to the grace of Thy promise” refer to the tradition that during their passion, each of these Saints received a promise from God that their intercession would be exceptionally effective on behalf of those who honored them. Thus, the third antiphon of Lauds in the proper office of St Catherine reads “I await the sword for Thee, o Jesus, good king; set Thou my spirit in Paradise, and show mercy to those who keep my memory.” To this Christ answers in the fourth antiphon: “A voice sounded from heaven: ‘Come, my chosen one, come, enter the chamber of Thy spouse; thou hast obtained what thou asked; those that praise thee shall be saved.” And the fifth concludes, “Because we keep the memory of thee, o virgin, with devout praises, pray for us, we ask, o blessed Catherine.”

In these three roles, as Patron Saint of philosophers, as a bride of Christ, and as a Holy Helper, St Catherine stands out as a perfect response to the novelties of the Protestant reformers.

After serving for many centuries as the “handmaid of theology,” from the Fathers to

Boethius to St Thomas, and particularly after the great scholastic conquest of Aristotle, philosophy, and indeed reason itself, were cast out by Martin Luther as “the Devil’s greatest whore… who ought to be trodden under foot and destroyed, she and her wisdom…” And likewise, “Aristotle is the godless bulwark of the papists. He is to theology what darkness is to light. His ethics is the worst enemy of grace. He is a rank philosopher, … the most artful corrupter of minds. If he had not lived in flesh and bones, I should not scruple to take him for a devil.” As for St. Thomas, “he never understood a chapter of the Gospel or Aristotle … In short, it is impossible to reform the Church if Scholastic theology and

philosophy are not torn out by the roots with Canon Law.” St Catherine therefore serves as an example of the Church’s true tradition, one who successfully used philosophy in the preaching and teaching of the Faith.

|

| St Catherine and the Philosophers, from the Castiglione chapel in the Basilica of St Clement in Rome, by Masolino da Panicale, 1425-31. Note how she calmly counts off her reasons for believing the Christian faith, as the philosophers look in confusion in different directions. “We firmly confess this to thee, o emperor, that unless thou shall show us a more likely sect than these which we have followed hitherto; behold, we all convert to Christ, because we confess Him to be true God and the son of God.” (from the Sarum Breviary). At this the emperor orders them to be burnt alive, as seen on the right. |

The Protestants also completely rejected any kind of monastic or canonical religious life, leaving no formal place at all for women in the institutional life of the Church. (Luther himself, like so many disaffected religious, married a former nun, whose name, ironically, was Catherine.) The tradition of Christ accepting her in a mystical marriage would therefore validate the institution of consecrated life in general, but particularly for women.

Finally, as a Saint renowned for her powerful intercession on behalf of many classes of people, St Catherine stands with countless others in the “cloud of witnesses” against the early Protestant rejection of devotion to the Saints, and their power to intercede for us in this world.

Even within Luther’s lifetime, it was hardly possible to get two Protestant reformers together to agree on any point; hence, the famous dispute at which he carved “EST – it is” into the table, in reply to Zwingli, who was quite certain that the Lord was only kidding when He said “This IS my body.” Broadly speaking, however, they generally accepted that things had really gone wrong in the Church with the coming of the mendicants, (especially the Franciscans), and the flourishing of their teachings in the universities. Although the life of St Catherine may no longer be regarded as historical, it still bears witness to the Church’s historical belief, before the emergence of the mendicants, in the goodness of reason and philosophy, in the value of consecrated life, and the intercession of the Saints on our behalf.

.jpg)

_-_S.Stephen_the_Younger.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)