The following article forms the foreword to the newly republished edition of Hubert van Zeller’s Approach to Christian Sculpture, reproduced here with permission of the publisher. The new and entirely re-typeset edition is available internationally, directly from the publisher, Barns & Noble, or Amazon. A musician, visual artist, and writer, Julian Kwasniewski is Marketing and Communications Coordinator at Wyoming Catholic College. His writings have appeared in numerous venues, including The National Catholic Register, Catholic World Report, The Catholic Thing, Crisis Magazine, Salvo Magazine, Latin Mass Magazine, and The European Conservative.

When Hubert van Zeller writes that “religious carving is meant to be a plea for light and truth, not for charm,” he expresses a truth which is just as relevant today as in 1959 when he wrote the book you are now holding in your hands. This monk and sculptor was concerned with “the present lack of direction in Christian sculpture” in both technical and spiritual approaches. Van Zeller’s idea that “before a piece of sculpture can be called Christian we must be sure that it can be called sculpture” is of course applicable to all mediums, and unfortunately just as (if not more) forgotten in our day than in his. Consequently, despite the fact that van Zeller and many of his contemporaries who appear on the pages of this book are now nearly forgotten, the problems which this author identifies—and the solutions he proposes for them—remain current.

Van Zeller was a remarkable man, and the more I familiarise myself with his extensive literary output, the more my esteem for him increases. Van Zeller would have been the first to admit that before he an author or sculptor he was a monk. The first two sentences of his autobiography are: “Religion is ordinary or extraordinary according to the way you look at it. So is sculpture.” (Hubert van Zeller, One Foot in the Cradle; An Autobiography (New York; Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1959), xi) Thankfully van Zeller looked at both religion and sculpture in such a way as to find them exciting. In numerous other books he has treated of the first, in the present work he addresses the latter.Born in 1904 in Egypt to British parents, van Zeller remembers in his autobiography his first experiments with carving as a child. It was at the age of seven or eight that he decided what he “wanted to be good at before all else.” Picnicking and boating with family and friends on a small island was the occasion. But “this time the picnic had no appeal for me. All I wanted to do was to get back to the beach on the mainland where I had seen an Arab boy with a small assortment of knives in his lap cutting bits of black washed-up wood into shapes.” Something about the Arab boy’s task resonated with the young Hubert. Though he “possessed neither material nor tools,” van Zeller promised to carve a face in a piece of wood for a friend, so sure was he “that the power lay somewhere inside” that he “could afford to take risks.” The craze for carving which ensued was so strong that his parents believed it “would burn itself out in a week.” Carving was his passion, not merely a hobby. (Ibid. 39-46)

Van Zeller recognized the intensely therapeutic nature of carving for him, throughout his life. “Whether it was a physical effort or not,” carving was “the outlet” even in times of convalescence from illness. Stone cutting was an activity he pursued his whole life, and he unsurprisingly developed a method and philosophy of sculpture: “working in company has enabled me to benefit by the ideas of others, working in solitude has enabled me to form my own,” he wrote in the preface to this book.

Several aspects of art and its successful pursuit form the burden of this present work. If interest in sacred art was wanting not only in general but was especially “wanting among those who are in a position to steer its course” in the author’s day, the same is true in ours. The result is that “this book is accordingly addressed to a variety of readers. For the layman and priest alike, it is meant to clarify the issues at stake; for the stone-carver it is meant to make more precisely religious the employment of his powers; for the non-Christian it is meant to explain what our artistic tradition and sculptural effort are about.”

It is the final three chapters of this book, however, which form its most valuable contribution to the scene of Catholic art, since they examine the relationship of the Church to the artist and the artist to his work. “It can be claimed,” writes van Zeller, “that sacred sculpture can develop only under certain conditions. Of these the primary condition is collaboration between the Church and the craft.” If the craft of sculpting has not fundamentally changed since van Zeller’s day, what of the Church?

As to its actual texts, the Council took a surprisingly traditional stance on church art:

“Very rightly the fine arts are considered to rank among the noblest activities of man’s genius, and this applies especially to religious art and to its highest achievement, which is sacred art. These arts, by their very nature, are oriented toward the infinite beauty of God which they attempt in some way to portray by the work of human hands; they achieve their purpose of redounding to God’s praise and glory in proportion as they are directed the more exclusively to the single aim of turning men’s minds devoutly toward God.

Holy Mother Church has therefore always been the friend of the fine arts and has ever sought their noble help, with the special aim that all things set apart for use in divine worship should be truly worthy, becoming, and beautiful, signs and symbols of the supernatural world, and for this purpose she has trained artists. In fact, the Church has, with good reason, always reserved to herself the right to pass judgment upon the arts, deciding which of the works of artists are in accordance with faith, piety, and cherished traditional laws, and thereby fitted for sacred use.

The Church has been particularly careful to see that sacred furnishings should worthily and beautifully serve the dignity of worship, and has admitted changes in materials, style, or ornamentation prompted by the progress of the technical arts with the passage of time….

Thus, in the course of the centuries, she has brought into being a treasury of art which must be very carefully preserved. The art of our own days, coming from every race and region, shall also be given free scope in the Church, provided that it adorns the sacred buildings and holy rites with due reverence and honor; thereby it is enabled to contribute its own voice to that wonderful chorus of praise in honor of the Catholic faith sung by great men in times gone by…

Let bishops carefully remove from the house of God and from other sacred places those works of artists which are repugnant to faith, morals, and Christian piety, and which offend true religious sense either by depraved forms or by lack of artistic worth, mediocrity and pretense…

It is also desirable that schools or academies of sacred art should be founded in those parts of the world where they would be useful, so that artists may be trained.

All artists who, prompted by their talents, desire to serve God’s glory in holy Church, should ever bear in mind that they are engaged in a kind of sacred imitation of God the Creator, and are concerned with works destined to be used in Catholic worship, to edify the faithful, and to foster their piety and their religious formation.” (Sacrosanctum Concilium 122-24, 127)

One reads such texts today with a sense of astonishment at how very far in the opposite direction everything went–not just after the Council, but even after 1963 when this document was approved and before the Council even closed. For it was in 1963 that the Consilium was established, which brought with it a spirit at least of questioning and revising, if not rejecting, much that came before.

Van Zeller is clear: “The liturgy…is taken to be the key to the whole thing. It is also the yardstick by which the carvings themselves are measured.” Unsurprisingly, then, art floundered when the liturgy floundered, if it is true that “it will be the liturgy which gives the note to the statues, decoration, arrangement,” as van Zeller puts it. Yet the liturgy remains the key to understanding what standards art should be measured by, and what better body of liturgical rites than than those we know gave rise to the greatest and most legitimate artworks in Western history, the traditional Latin rites of Europe?

Van Zeller recognizes, though, the risks inherent in a liturgical aesthetic, noting “the risk either of drawing liturgy towards aesthetics, which would be bad theology (for liturgy is a directly and essentially religious reality, hence much more than a thing of aesthetical experience), or else of elaborating a non-aesthetic philosophy of art.” Van Zeller then references several Vatican instructions on modern art, which he sums up in the following words: “What all this amounts to, then, is this: let the moderns go ahead with their work, but let them show an acute consciousness of the reverence due to God and to the house of God.” This is achieved by avoidance (in the words of Mediator Dei) of anything which is a “deformation of sane art”, though, as van Zeller remarks, “the point at which sane art leaves off and mad art begins is not altogether clear.”

Prophetically, van Zeller wrote that “the Church has the duty, at this time especially, of being on its guard” because in “the confusion of ideologies, each eventually bringing to the surface its own appropriate expression, the Church can take no risks.” “Artistic expressions must be held up steadily and long before the light of truth,” and “whether a work of art survives the test of time is often a measure of its truth: if it is not true, it is of no consequence and the sooner it perishes the better....Perhaps the chaotic state of modern art, secular particularly but religious also, is the prelude to another great resurgence such as Christian centuries have witnessed in the past.”

One of van Zeller’s main questions is: what ought we to want from sculpture–what is its meaning? “If we look back, we see that all periods of Christian sculpture have meant something, even if it was something which was not immediately understood. Christian sculpture of the present day, however obscure the message which some of it may bring, means something. The truth of it is that the generality of the faithful, whatever the period, want sculpture to mean what they mean. It would be more humble if they wanted it to mean what God means.” Joseph Shaw has recently commented admirably on religious and specifically liturgical “intelligibility” in the liturgy, noting that the understanding of the significance of a text or work of art should not be confused with its direct intelligibility. (See chapter 4 of “Understanding Liturgical Participation” in The Liturgy, the Family, and the Crisis of Modernity: Essays of a Traditional Catholic (Lincoln, NE: Os Justi Press, 2023), 57ff.)

I believe van Zeller expresses the same thing: “The sculptor is trying to get nearer to truth; Catholicism is telling him where to look, and how to get there, and what it is.” One of the things Catholicism’s tradition teaches is that immediate intelligibility is not the highest good when it comes to sacred worship, and therefore by extension, sacred art. Another thing it tells the artist is that he is always drawing upon his predecessors and must harmonise his innovations with theirs. In the words of the author:

Tradition, like nature, is to the sculptor the background against which he works. It does not determine his manner, which is an individual thing, but it probably conditions his having a manner at all. Very few sculptors, however creative, can work entirely out of their heads. Even those who think that they work entirely from their own reserves are in fact drawing upon the law of sculptural heredity. Anyway if they repudiate an ancestry, sculptors will produce only ill-bred, vulgar work.

The idea that religious inspiration dispenses from skill is certainly problematic in all areas of art. For example, in recent years Irina Gorbunova Lomax has written powerfully of this tendency in the world of Iconography. “The sculptor who is true only to his religious aspiration and not to the principles of his craft may produce works of interest, and even of edification, but these will not be works of Christian art.” (Irina Gorbunova-Lomax, The Icon: Truth and Fables (Brussels: Brussels Academy of Icon Painting/China Orthodox Press, 2018))

This brings us to the heart of this book’s relevance today: if sentimental kitsch, grotesque abstraction, anti-incarnational simplicity, or hyperrealistic romanticism continue to dominate the world of religious artwork today, the diagnoses of these ills and the solutions to them that van Zeller proposes remain timely. Prayer, van Zeller ultimately claims, is fundamental for truly religious artwork of high quality, as is dialogue with tradition, mastery of technique, respect and understanding of materials, and fidelity to one’s own artistic sensibilities and vision.

|

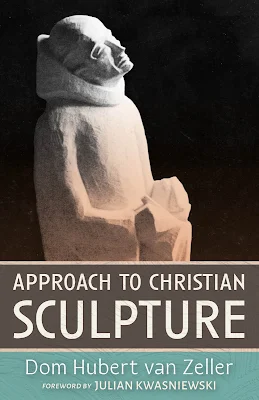

| Sculptures of the Madonna and Child and St Joseph by Van Zeller. |

Just because I happen to think that the Romanesque represents the peak of Christian sculpture, and that the Gothic Revival represents the depths, I do not demand the agreement of my readers. The most that I would ask of a reader would be the patience to note the reasons which I might advance for my view. Every book about art, as about all subjects that are worthwhile, is a personal book.

I would second this sentiment: even if van Zeller’s artistic output and opinions do not resonate with you, nonetheless his reasons are carefully thought out and worthy of pondering.

In the context of Gothic Revival, his main concern is that it produces false works because it imitates a certain style exteriorly without being able to replicate the interior state which gave genuine rise to the original exterior expression. This is a valid concern for any style, Bauhouse as much as Gothic, Romanesque as much as Art Nouveau. An interior fidelity and harmony is required for an exterior counterpart: “More important than fidelity to one’s material is fidelity to oneself….The sculptor who produces works which do not express himself but someone else is making use not of a creative but of an imitative gift.”

“For a style of carving to be copied, its inspiration has to be experienced,” he writes. “It is no good trying to work out one’s own problem according to another man’s solution. Truth appears to us in its way, and we respond to it in ours” is an idea that van Zeller takes up in his more properly spiritual works Sanctity in Other Words and We Live With Our Eyes Open. In the first he remarks how we can draw inspiration from various aspects of the lives of the saints but can’t ever “photocopy” them in the path of our own life. Each person is unique. The sculptural echo in this book is his statement that “while there is no harm in following one school of sculpture rather than another, there is harm in following one school so closely that the individual creative spark is smothered.”

In We Live With Our Eyes Open, van Zeller comments on truthfulness in prayer and the common desire to use someone else’s words when really we ought to form our own:

God in any case has seen into your mind before you have, and if there is really nothing there for the time being He won’t in the least resent your being honest about it. This is to be true, to be humble; it is what He wants. Certainly it would be a mistake under such circumstances to fall back upon a sentiment which looks the sort of thing one ought to feel, merely for the sake of finding something—incidentally something not quite true—to talk about. (We Live With Our Eyes Open (Stamullen: The Cenacle Press at Silverstream Priory, 2023), 71.)

It would be fascinating if van Zeller had applied this idea to art: that if we have nothing genuine to say, it might be better not to produce than to produce false works of art.

For van Zeller, the Romanesque is the epitome: “in the Romanesque conception, indeed, theology and aesthetics were one. Such a union had not been achieved before, and it has been achieved since only for the briefest periods and in particular regions.” The architectural origins of Romanesque style gave its sculptural aspect “discipline, balance, and three-dimensional design.” If we look to a Romanesque Madonna for “for human loveliness we are disappointed, but we find instead a dignity and power which are far more moving.”

Though we may not agree with the author in this or that particular assessment of his, the reprinting of this deeply reflective book should be welcomed by all Catholics who take interest in promoting or practising the arts, both sacred and profane. As an historical snapshot it provides, along with several other of van Zeller’s books, an important window into his time period, which was one of such promise, effervescence, confusion, and bewilderment–in that way, not unlike our own. As the meditation of a life-long sculptor and Catholic priest, its claims deserve careful consideration. May it inspire not only truer art but truer Christianity in a new generation of readers.