St. John the Baptist, whose birthday we celebrate on June 24, is well represented in the Gospels and even in every celebration of the traditional Latin Mass. Yet while devotion to other Saints close to Jesus, such as St. Joseph, has grown over the centuries, Western piety seems slightly neglectful of the one whom the Eastern churches call the Forerunner of the Lord. That is a shame, for the Saint who represents the last and best of the Old Testament has, as we shall see, a surprising relevance for this late chapter in Church history.

Biblical Prominence

Saint John the Baptist plays a prominent role in all four canonical Gospels. After recounting Christ’s genealogy and infancy, Matthew proceeds straight to his ministry (Matthew 2). Mark begins his “gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Mark 1, 1) not with Jesus Christ the Son of God but with “the voice of one crying in the desert,” John the Baptizer. (1, 3-4) Luke opens his Gospel with the story of John’s conception, (Luke 1.5-25) and Saint John the Evangelist, in an astonishing move, interrupts his magnificent prologue about the Word becoming flesh and dwelling among us with a disclaimer that John the Baptist was not the Light but an important witness to the Light. (John 1, 6-10)

Conception and Naming

John’s conception in the womb of his mother Saint Elizabeth follows a hallowed tradition of miraculous conceptions. Isaac’s mother Sarah was beyond child-bearing, (Gen. 17, 19) and so was Samson’s, (Judges 13, .3-24) but the Most High brought life out of their barrenness.

John’s naming also follows a biblical pattern. Among adults, God renames chosen vessels as a sign of their new mission. Abram becomes Abraham, Sarai becomes Sarah, Jacob becomes Israel, and Simon bar Jonah becomes Saint Peter. But for specially chosen vessels, the naming takes place in the womb. Isaac is the name that the Lord God gives to the miraculous offspring of Abraham and Sarah, Jesus is the name that the Archangel Gabriel reveals for the incarnate Son of God, and John is the name, according to the same angel, for His second cousin.

Unlike the Blessed Virgin Mary’s unconditional fiat, John’s father receives the news about his son’s conception and naming in a spirit of doubt. As a result, Saint Zechariah or Zachary is punished by being struck dumb, a curse is not lifted until it is time to name the child eight days after his birth, at his circumcision:

And it came to pass, that on the eighth day they came to circumcise the child, and they called him by his father's name Zachary. And his mother answering, said: “Not so; but he shall be called John.” And they said to her: “There is none of thy kindred that is called by this name.” And they made signs to his father, how he would have him called. And demanding a writing table, he wrote, saying: “John is his name.” And they all wondered. And immediately his mouth was opened, and his tongue loosed, and he spoke, blessing God. And fear came upon all their neighbours; and all these things were noised abroad over all the hill country of Judea. (Luke 1, 59-65)

Note the wording. Zachary does not say, “He will be called John,” but “His name is John.” Zachary is, in other words, uttering the essence of his son’s identity, not randomly assigning a label that happens to fall short of Jewish naming conventions at the time. In so doing, he is like Adam in the Garden, who names the beasts according to their essences. (see Gen. 2, 20) It is this act of faith that frees him from the angel’s curse and liberates his tongue.

It is also noteworthy that Zachary’s wife Saint Elizabeth, who must have learned about the angel’s message from her husband in writing, believes Saint Gabriel wholeheartedly. Her insistence on the name John despite her relatives’ protest is rather comical in the Latin Vulgate translation: Nequaquam! Which, if we were to translate it into modern slang, would be: “No way!”

Gestation

John was conceived in the normal fashion (unlike Our Lord), and yet his gestation in the womb was accompanied by a miracle. When the Blessed Virgin Mary, who bore a less-than-one-month-old Son of God in her womb, visited her aged cousin Saint Elizabeth, who was six-months’ pregnant with Saint John, something amazing happened:

And [Mary] entered into the house of Zachary, and saluted Elizabeth. And it came to pass, that when Elizabeth heard the salutation of Mary, the infant leaped in her womb. And Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Ghost: And she cried out with a loud voice, and said: “Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb. And whence is this to me, that the mother of my Lord should come to me? For behold as soon as the voice of thy salutation sounded in my ears, the infant in my womb leaped for joy. And blessed art thou that hast believed, because those things shall be accomplished that were spoken to thee by the Lord.” (Luke 1, 40-45)

The Visitation, 1306, by Giotto, in the lower basilica of St Francis in Assisi.

How did the preborn John the Baptist recognize the voice of the Mother of God? And how did he know that he was in the presence of the Messiah? Not only was Saint Elizabeth filled with the Holy Ghost, but so was her son. (see Luke 1, 15) John the Baptist is considered by Catholic tradition to be like Jeremiah the prophet, who declares that he was sanctified in the womb. (See Jeremiah 1, 5) And consequently, both Jeremiah and John are on a small list of saints who never committed a sin, either venial or mortal, in their lives. Unlike the Blessed Virgin Mary, John was conceived in original sin, but while he was in the womb he was purged of the stain of original sin and went on to live without personal sin. No wonder that his is the only earthly birthday, besides that of Our Lord and Our Lady, that is honored on the Church calendar.

Moreover, Luke’s account of the Visitation bears a striking resemblance to David’s greeting of the Ark of the Covenant, when he dances before the Ark half-naked—much to the chagrin of his wife Michal. (see 2 Kings [2 Samuel] 6, 14-16) Just as David danced before the old Ark of the Covenant, John dances in his mother’s womb before the New Ark of the Covenant, the Tabernacle that is Mary the Theotokos, the God-bearer.

Early Years

The Holy Bible has only two sparse lines about the youth of John the Baptist: “He grew and was strengthened in the Spirit” and “He was in the desert until the day of his manifestation to Israel.” (Luke 1, 80) The rest is speculation. It is widely conjectured that after the death of his parents (who, because of their age, died when he was relatively young), John went into the desert and joined the Essenes, an ascetical and messianic Jewish community. If this is true, he may have adopted certain customs of theirs, such as ritual washing or “baptizing,” but in a way that would have scandalized them.

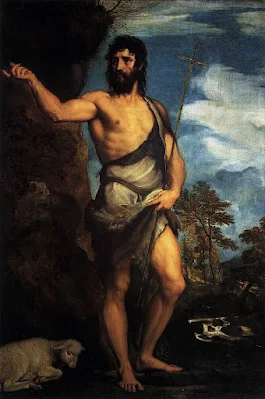

Titian, 1542

Description

Unlike other literature, the Bible is rather taciturn about how its characters look or what they eat, and when it does divulge this information, it is to reveal something important. John the Baptist is described in one fulsome verse:

And John was clothed with camel’s hair, and a leathern girdle about his loins; and he ate locusts and wild honey. (Mark 1, 6; see Matthew 3, 4)

Most artists portray the Baptist looking like Tarzan or a caveman, with a one-shoulder tunic made out of camel hide. Nevertheless, the sacred text states that he wore hair rather than a pelt, which would have been more in keeping with his Nazarite vow not to touch dead bodies (more on this vow later). On the other hand, his wardrobe is not to be confused with the fashionable coats worn today. Camels have two kinds of hair: a fine, soft undercoat from which contemporary camel hair coats are made, and a coarse outer guard hair that is the fabric for haircloth and hairshirts. Given his ascetical life, he probably wove his own clothing from the rough guard hair that he could have picked up off the ground, since camels shed this hair in the spring and summer. No wonder that Saint John the Baptist is the patron saint of tailors.

His leather belt is significant because the prophet Elijah also wore one. The Pharisees’ suspicion that John the Baptist was Elijah returned is not as insane as it might sound initially. (See John 1, 21) Elijah never died but was assumed into heaven in a fiery chariot; he wore a leather belt and lived apart; and he openly criticized the marriage of the king and his wife, Ahab and Jezebel, like John’s condemnation of the marriage of Herod and Herodias. John fits the profile of the Old Testament’s greatest prophet.

Biblical scholars have debated the meaning of “locusts.” Some have suggested that it was carob tree beans, others that it was a kind of manna-like pancake. But the Greek word clearly points to locusts, which are still eaten in the Middle East (Bedouins like theirs sun-dried and salted). Curiously, locusts are one of the few insects permitted as a clean comestible under the Mosaic Law.

A vendor in Yemen selling dried locusts

Scholars also quibble over the meaning of “wild honey,” some claiming that the reference is to gum from the tamarisk tree, which is nutritious but bland. Saint Jerome speculates that because the honey was wild, it was bitter in taste. He may be right, although it would depend on the nectar and pollen available to the bees. Either way, it must have been difficult to harvest the honey and even painful to do so (lots of stings), since wild bees usually have hives in inauspicious locations such as tree trunks, rock crevices, etc.

John was also predicted by Saint Gabriel to be a teetotaler, drinking neither wine nor strong drink. (Luke 1, 15) This restraint, combined with his holiness, identifies the Baptist as one of three persons mentioned in the Bible who took a lifelong vow of the Nazarite, the other two being Samson and Samuel. (See Judges 13, 4-7; 1 Samuel 1, 11) During the duration of his vow, a “Nazarite” (nazir is the Hebrew word for consecrated or set apart) could not cut his hair, drink alcohol or ingest anything from the grape, or touch corpses and graves.

Finally, Our Lord mentions that John neither ate bread nor drank wine. (See Luke 7, 33) A diet without bread further illustrates Saint John’s wildness, for bread, like wine, is a product of civilization. But mentioning bread and wine together also has unmistakable Eucharistic overtones. John was great, despite never feasting at the Eucharistic sacrifice of the Lord.

Preaching

John’s mission was to prepare the way of the Lord, (Matthew 3, 3) and he did so by preaching repentance. He is famous for fearlessly calling the Pharisees and Sadducees “a brood of vipers.” (Matthew 3.7) and for speaking out against Herod’s marriage to his sister-in-law. On the Collect of his feast, the Church prays that we may learn to “boldly rebuke vice” like Saint John.

This petition, however, needs to be understood properly. Contrary to a popular misrepresentation, John was not an arrogant hothead, but a gentle spiritual director. As St. John Henry Newman astutely notes, Herod continued to like Saint John after the latter rebuked him; therefore, the Baptist must have rebuked him well—

that is, at a right time, in a right spirit, and a right manner. The Holy Baptist rebuked Herod without making him angry; therefore he must have rebuked him with gravity, temper, sincerity, and an evident good-will towards him. On the other hand, he spoke so firmly, sharply, and faithfully, that his rebuke cost him his life. [1]

Similarly, when tax collectors asked him for advice, he did not tell them to quit their job working for the despised Romans but simply not to cheat anyone. And when soldiers (presumably, Gentiles in the service of Rome) asked what to do, John did not condemn them or their occupation but told them not to use their position to do bully others and to be content with their pay. (Luke 3, 12-14) John most likely baptized these soldiers as well, touching them as he dipped them in the River Jordan—something the Essenes, who valued their ritual purity, would never have done.

Baptizing with Water

Another difference between John and the Essenes is the significance each attached to purification through water. The Essenes had a ritual washing every day, but it was not related to a remission of sins. John’s baptism was different. Although the Baptist makes clear that his baptisms did not absolve sins and that only baptism in water and the Spirit would, he nevertheless preached “a baptism of penance for the remission of sins” (Luke 3, 4), and he never baptized unless the penitent confessed his sins. (Matthew 3, 6) John’s baptism served the crucial purpose of making people aware of the sins that are remitted in the Sacrament of Baptism.

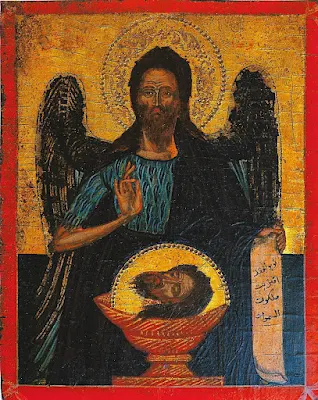

Martyrdom

The details of Saint John the Baptist’s martyrdom are well known. After criticizing Herod’s marriage, the monarch imprisoned him, even though he liked him. For his own birthday, Herod threw a large party and inviting several dignitaries. When Herodias’ daughter danced for him, Herod was so moved that he promised to give her anything that she wanted. At her mother’s behest, Salome (as she is known by tradition) requested the head of John the Baptist on a platter. The sad king obliged because he could not lose face in front of his important guests.

For centuries it was assumed that among the Elect, St. John the Baptist was second only to the Blessed Virgin Mary in holiness. There is a Byzantine iconographic tradition called the Deesis that portrays the Mother of God and John the Baptist on either side of Jesus Christ, and similar depictions exist in Western art as late as the seventeenth century. Hence, when the Roman Litany of Saints was being formalized in the sixteenth century, John’s name was placed ahead of that of St. Joseph.

A Deesis icon

By the nineteenth century, devotion to St. Joseph in the West led to a reconsideration of the matter. Pope Leo XIII taught that Joseph “approached nearer than any to the eminent dignity by which the Mother of God surpasses so nobly all created natures.” [2] The Supreme Pontiff gave two reasons: 1) Marriage is so profound a union that some of Mary’s holiness must have rubbed off on Joseph. And 2) Joseph is the only man to whom the Son of God subjected himself like a son. Surely, God would have endowed a man of such unique dignity with extraordinary holiness.

Altar piece in Braga Cathedral (Portugal) depicting the Blessed Virgin and St. John the Baptist (along with St. Michael) delivering souls out of Purgatory. St. Joseph is not pictured.

Leo may be accused of an idealistic view of matrimony, for not everyone is sanctified by a holy spouse (some married stinkers choose to remain stinkers). Nevertheless, his logic is grounded in a solid biblical pattern. In the Holy Tabernacle, the closer the sacred furniture was to the Ark of the Covenant, the “holier” it became. Mary is the new Ark of the Covenant, and the person closest to her besides her Divine Son is Joseph. [3]

Such reasoning does not satisfy the Eastern Orthodox, who critique the “promotion” of Saint Joseph as yet another Western innovation. [4] In addition to the tradition that John was without personal sin, they point to the words of Our Lord Himself:

Amen I say to you, there hath not risen among them that are born of women a greater than John the Baptist: yet he that is the lesser in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he. (Matthew 11, 11)

Luke’s Gospel appears to backpedal a bit by adding the word “prophet”:

For I say to you: Amongst those that are born of women, there is not a greater prophet than John the Baptist. But he that is the lesser in the kingdom of God, is greater than he. (Luke 7, 28)

There are three things to note about these passages. First, they are paradoxical. Both state that John is the greatest, except that he isn’t. Whoever is lesser in the Kingdom is greater than he. That could mean one or more people are greater than he. Both Catholic and Orthodox believers, for example, believe that Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary are greater than John the Baptist.

Second, the identity of who is “the lesser in the kingdom of God” is unclear. Patristic and medieval theories include Jesus Christ, the Angels, the Apostles, and the Saints in Heaven (who are “greater” insofar as their struggle on earth is over).

Third, and most importantly, there has been a great deal of attention paid to the words “among those born of women” and little attention to what could be the more important qualifier: “there hath not risen among them.” Egeiró, the Greek verb translated here as “risen,” can also mean “to cause to appear before the public.” If this meaning is kept in mind, then the Lukan verse is not a backpedaling but a rephrasing of Matthew’s wording, for a prophet is one who is called or caused by God to appear before the public on His behalf.

Our Lord, in other words, is talking not about John’s sanctity but his vocation as the prophet who makes straight the way of the Lord. John is the herald of the Messiah; no other holds this honor. Great though they be, neither Mary nor Joseph was called to be a prophet or public figure. Mary never speaks to a general audience in public, only to private persons (e.g., her Son, the waiters at the Wedding of Cana, etc.), and Joseph does not have a single word of his own recorded in the Bible.

In any event, it is silly to pit Saint Joseph against Saint John the Baptist, as if they were vying for who is the greatest, like the Apostles before they grew spiritually mature. (see Mark 9.33) Both John and Joseph are part of the same Holy Family, interceding for us in Heaven, and there is no emulation among them.

Jacopo Pontormo, "Madonna and Child with St. Joseph and St. John the Baptist," ca 1521

Ongoing Role

John is a transitional figure; as a combination of elements from the Patriarchs and prophets, he represents the Old Testament recognizing the New. It is therefore tempting to think of John the Baptist as outdated after our redemption has been accomplished. Yet Saint John the Baptist is surprisingly relevant in this penultimate chapter of Church and world history.

First, John preaches repentance (something our age sorely needs) and, as we noted earlier, he preaches it well. The Baptist cultivated a character that was “discreet, unexceptionable, and graceful,” thus serving as a model for us all. Again Newman:

The single-hearted Christian will find fault, not austerely or gloomily, but in love; not stiffly, but naturally, gently, and as a matter of course, just as he would tell his friend of some obstacle in his path which was likely to throw him down, but without any absurd feeling of superiority over him, because he was able to do so.[5]

And, it may be added, John’s witness to the truth included a defense of the sanctity of matrimony, a defense that is increasingly needed today.

Second, the secret of Saint John’s firm gentleness was his self-effacing humility. For probably several years, the Baptist’s ministry was front-page news: crowds thronged to the river Jordan to hear him and be baptized, the “influencers” of the day sent delegates (or spies) to watch him, and potentates knew of him. Yet all his words and deeds regarding Jesus Christ reveal a profound self-abnegation. John declares that he is not worthy to loosen the strap of the Messiah’s sandal (Luke 3.16) and that he must decrease while the Lord must increase. (John 3.30) And when the time was right, he sent all his disciples to Jesus of Nazareth. The Benedictine spiritual master Dom Hubert van Zeller once observed that “it is an art in life to put up with being second best.” Saint John the Baptist perfected that art; he not only put up with being Jesus’ inferior, he relished it. If we could do that as well, we too would become saints.

This article originally appeared in The Latin Mass magazine 32:2 (Summer 2023). Many thanks to its editors for allowing its publication here.

Notes

[3] Gary Anderson, “Mary in the Old Testament,” Pro Ecclesia XVI:1, pp. 33-55.

[4] S. Bulgakov, “St John the Forerunner and St Joseph the Betrothed,” excursus 3, The Friend of the Bridegroom: On the Orthodox Veneration of the Forerunner (Cambridge, 2003), pp. 177-88.

[5] Newman, Sermon 24.

[6] Letters to a Soul (Cenacle Press, 2023), 1.