Yves Chiron is a reputable French scholar whose specialty is nineteenth- and twentieth-century Catholic history. Chiron has written biographies of Edmund Burke, Pius IX, Pius X, Benedict XV, the seers of Fatima, Pius XI, and Padre Pio. In 2020 he published the

Françoisphobie: François Bashing, and in February 2022

Histoire des Traditionalistes, the fruit of over twenty years of research (I have heard that an English translation will be coming out in 2024). Chiron’s biography of Archbishop Annibale Bugnini, which appeared in French in 2014 and in English in 2018, is considered the best and most thorough treatment so far on the controversial liturgical reformer.[1]

In 2003, Chiron published a biography of Pope St. Paul VI, and in 2008 a revised edition. Chiron did not alter his appraisal of the pontiff but added several clarifications and new points of view that came to light after the publication of the first edition. He also expanded on several points from the first edition, such as the influence of Jacques Maritain on the political thought of Paul VI.

Thanks to translator James Walther and Angelico Press, the 2008 edition was made available in English last year under the title

Paul VI: The Divided Pope.

Walther’s translation is smooth and readable, and it includes additional footnotes about some of the persons and movements in Paul VI’s life.

The new edition also begins with a foreword by Henry Sire. Sire, a historian of modern Catholicism and a papal biographer himself, offers a spirited analysis of the pontificates of Paul VI and Francis, noting the parallels between how the two pontiffs were elected and the tension between their goal of liberalizing the Church and their autocratic ruling styles. If Paul VI is the Divided Pope, Sire concludes, Francis is the Divisive Pope. Catholics who are worried about the so-called Francis effect can thus gain a better perspective by understanding the pontificate of Paul VI.

Chiron’s own approach is more dispassionate: “The historian is not a judge or arbitrator,” he asserts in a recent interview. “The most he can do is to be rigorous in his research and in the portrait he draws.”[2]

Montini at his ordination to the priesthood, 1920

Paul VI: The Divided Pope bears witness to that rigor. Chiron canvases the family of Giovanni Battista Montini (Paul VI’s baptismal name), their involvement in left-leaning and anti-fascist Italian politics, and Montini’s erratic seminary formation, which occurred without his living in a seminary due to poor health. Chiron goes on to chronicle Montini’s involvement in Vatican politics, serving under Pius XI and Pius XII. The latter relied on him in many matters, but for reasons unknown distanced himself from the talented apparatchik, “exiling” him from the Holy See’s inner circle to serve as Archbishop of Milan in 1954.

It was the first official pastoral experience in Montini’s life, and it did not go as expected. To combat a religious decline in Milan, the Archbishop launched a renewal campaign called the Great Mission that was designed to “reform” and “modernize” the Church and increase the piety of lay Catholics. But “after a brief eruption of fervor, the results of the Great Mission were profoundly disillusioning,” and Milan’s slide into secularism continued. (142)

Cardinal Montini of Milan, 1959

Montini returned to the limelight during the pontificate of Pope St. John XXIII, but he was a behind-the-scenes player during the early sessions of Vatican II in order to maintain an air of nonpartisanship. During this period, the Archbishop grew closer to Cardinals who would elect the next Pope; during a tour of North America in 1960, he befriended five American and two Canadian Cardinals, all of whom supported him in the conclave following the death of John XXIII. He also attended a meeting at Grottaferrata that has been compared to the “Gallen Mafia” meeting that is claimed to have influenced the election of Pope Francis.

Montini was elected Pope on only the second day of voting in large part, to quote Cardinal Ildebrando Antoniutti, because of an “underlying sentiment that the Church was likely headed towards a crisis which the Council had created, so that it needed a regulator with whom all sides could be associated in order to broker a resolution.” (170) At the time, the seasoned diplomat and Vatican insider seemed the obvious choice, but as it turns out, brokering resolutions to the crisis that he was instrumental in causing was not his strong suit. Montini took the name Paul after the great missionary Apostle, but he ended up not quite being all things to all men in the same way as his new namesake.

Paul VI’s reactions to Vatican II and its aftermath oscillated between enthusiasm and despair. The Council became increasingly divisive with each new session, and before the fourth and final session Paul VI published a despondent encyclical (

Mense Maio) begging the People of God to pray the rosary so that things would end well. Paul VI’s spirits lifted a bit thereafter, but after 1968 he began to despair again and would soon be speaking of the Church’s “self-destruction” and how the “smoke of Satan” had entered into the sanctuary of God. From 1972 until his death in 1978, the Pope resigned himself to letting the Holy Spirit figure it all out and held loose the reins of governance (with, as we will see later, a couple of notable exceptions). Near the end of his life, a broken Paul VI complained that he had been abandoned and betrayed by his friends and allies.

Chiron’s descriptions of Montini are telling. Adjectives such as “brilliant,” “audacious,” and “cautious” are counterbalanced with “sentimental,” “naive,” and “unrealistic.” Chiron writes: “He was sometimes prone to let himself be swept away by emotion and act without reflection.” (157) And although the Pope’s “flights of lyricism” could be quite eloquent, they were not always clear or precise. In the closing speech to the Second Vatican Council, Paul VI scandalized many when he said: Nos etiam, immo nos prae ceteris, hominis sumus cultores. (234) The official Vatican version is: “we, too, in fact, we more than any others, honor mankind.”[3] The translation is accurate and probably reflects the Pope’s intentions, but the statement can also be translated: “We more than anyone, are worshippers of man.”

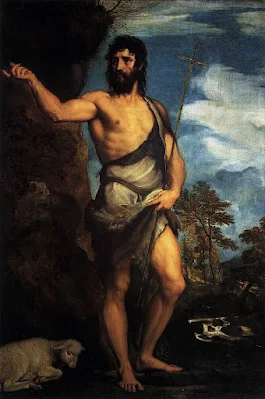

Paul VI at Vatican II

For Paul VI, who drank deep of Nouvelle Theologie’s “new humanism” and Jacques Maritain’s “integral humanism,” the declaration was tied to a “theocentric and theological concept of man.” Elsewhere in the same speech, the Pope describes the encounter between Christianity and secular humanism thusly: “The religion of the God who became man has met the religion (for such it is) of man who makes himself God.” Secular humanism, in other words, is a false religion that ironically does not understand or honor the human as well as the Catholic Faith. True enough, but the Pope’s articulation of this irony leaves much to be desired and understandably gave rise to a traditionalist backlash.

There are at least three reasons why Chiron is justified in calling Paul VI the Divided Pope. First, as one cardinal who knew Montini for years put it, “He was a pope who suffered from a dichotomy, with his head to the right and his heart to the left.” (227) As already noted, Giovanni Battista Montini grew up in a family steeped in leftist Italian politics (the Christian Democrats), and he was a champion of religious liberty and the separation of Church and state. On the other hand, the only time that Paul VI intervened in the final session of the Council was to take artificial birth control and priestly celibacy off the table; they were not negotiable (as they appear to be now under the current Pope).

A good illustration of this dichotomy is that within three months of each other, Paul VI published two encyclicals:

Sacerdotalis Caelibatus, a vigorous defense of the Roman tradition of priestly celibacy, and

Populorum Progressio, an endorsement of his friends’ integral humanism that championed economic development for all and “a world fund to relieve the needs of impoverished peoples” that was to be deducted from military spending. The document, which was pilloried by economists around the world and is rife with a jaw-dropping utopian naiveté, opened the door for liberation theology in Latin America.

Second, Paul VI was torn between maintaining changeless dogma and introducing sweeping changes to the Church’s liturgy, governance, and attitude towards other groups (other Christians, other religions, etc.). Paul VI had a penchant for dramatic and “spectacular gestures” that were designed to be disarming in order to invite dialogue yet were sometimes confusing. In 1964, Paul VI took off his tiara and announced that it would be sold and the proceeds given to the poor. (This was the same tiara on which he had spent money because he wanted something more modern in design!) But what did the gesture mean? Was it a renunciation of the Church’s claim to temporal power? Either way, the tiara was never sold. Paul VI gave it to his friend Cardinal Spellman of New York, and it was eventually put on display at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. The American bishops were “invited to offer a sum of money for the poor.” (192)

Paul VI's tiara at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception

Third, Paul VI was divided in his treatment of dissent. He was generous to a fault with his heterodox friends such as Hans Küng, whom he protected and refused to sanction. He was generous with adversaries of

Humanae Vitae (Frs. Karl Rahner, Bernhard Häring, Charles Curran, etc.) whom he refrained from disciplining and whom he protected from stricter bishops. He was generous with the Archbishop of Canterbury, to whom he gave his episcopal ring from Milan. He was generous with Greek Orthodox Metropolitan Meliton of Chalcedon, whose feet he kissed (when the astonished Meliton tried to reciprocate, the Pope refused). He was generous with the Turks, to whom he returned the great Ottoman battle standard that Christians had captured during the Battle of Lepanto. He was generous with Communist leaders, pursuing a policy of Ostpolitik that often backfired and left persecuted Catholics behind the Iron Curtain and in China at a disadvantage. And he was generous with Freemasons, calling for a revision of (the old) canon 2335 that referred explicitly to their excommunication.

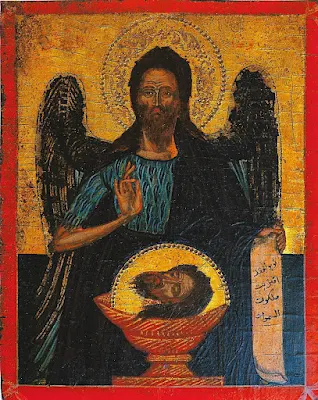

Paul VI Kissing the Feet of Metropolitan Meliton

But when Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre asked for an audience with the Pope to iron out their differences, Paul VI demanded “submission” as a condition for “dialogue” (in contradiction of his own extensive thoughts on the subject as expressed in his 1964 encyclical

Ecclesiam Suam). When Lefebvre finally got his audience (without submitting), he had the sense that the Pope felt “personally wounded” by the Archbishop’s criticisms and that the Pope was ill-informed of the situation: he accused Lefebvre of making his seminarians take an oath against the Pope, which was never the case. Paul VI, in turn, thought of Lefebvre as a “lost soldier” who belonged in a “psychiatric hospital” and who had an “insane and morbid obstinacy.” (286)

The Pope’s animus towards Lefebvre and the Traditionalists led him to make intemperate statements, as often happens in heated arguments. At least twice during his pontificate the Pope affirmed that while Vatican II was authoritative and authentic, it did not infallibly define any dogma. And yet when he saw that the judgment of the Council Fathers was being called into question by the Traditionalists, he declared that Vatican II “holds no less authority than that of the Council of Nicaea, and under certain aspects is even greater.” (284) You can imagine how that went over.

Marcel Lefebvre, ca 1962

Paul VI’s reaction to Lefebvre’s dissent is also noteworthy because it contrasts with his own record as a Vatican official. When he worked under Pope Pius XII, Montini sometimes acted “in direct opposition to [the Pope’s] authority,” (90) which is probably why he lost favor with Pius XII and was appointed Archbishop of Milan.

Chiron never answers the question why the Lefebvre case was so neuralgic for Paul VI. My own suspicion is that Paul VI was pleased to think of himself as a Modern Pope but not a Modernist Pope. From an early age, Montini loved modern art and modern literature, and he was obsessed with “modern man,” whom he both idealized and pitied as noble but tragic and on behalf of whom he was willing to make extravagant sacrifices in the realm of sacred liturgy and asceticism. Perhaps because of his long career in Vatican diplomacy and his cultural sophistication, he believed that he was well-poised to thread the needle, to maintain Church doctrine while updating the Church’s self-presentation, praxis, and organization.

And so, when Lefebvre declared that the changes Paul VI oversaw were “neo-Modernist and neo-Protestant,” the Pope probably took it as a personal attack (unlike his heretical friends, who were “only” attacking Church dogma). Thus, when even Hans Küng and Annibale Bugnini advised tolerance for both Lefebvre and the celebration of the old rite, Paul VI icily ignored them, and at the expense of his own principles. “I am first of all pardoned by God,” he told an associate at the end of his life, “I ought never to condemn anyone; I should always be the minister of pardon.” (12) Well, almost always.

Despite Chiron’s coverage of Paul VI and Marcel Lefebvre, I would have liked to learn more from this biography on Paul VI’s liturgical and ascetical decisions. It is from Chiron’s biography on Annibale Bugnini, and not from the one currently under review, that we learn that Paul VI wanted to restrict concelebration, to leave the Roman Canon untouched and to allow two or three additional anaphoras during certain defined seasons, and to retain communion on the tongue alone, the triple Agnus Dei, the Last Gospel, the Mysterium fidei in the words of consecration, all the minor orders, and the major order of subdiaconate. And yet with the exception of the Agnus Dei, Paul VI eventually approved the suppression of all these traditions. How did a pope who finger-wagged the Consilium in 1966 about reverencing the sacred, respecting tradition and a sense of history, and searching for what is best rather than what is new come to approve Bugnini’s vast innovations? Chiron’s biography on the sainted Pope does not tell us.

We do, however, learn that Paul VI thought of Latin in the liturgy as “sacred, grave, beautiful, highly expressive, and elegant,” but that it had to be “sacrificed” in order to increase active participation. (239) It was not an opinion universally received well. In Africa, most of the bishops preferred Latin as a unifying language over that of the colonizers’ or of the myriad tribal tongues that divided the peoples of that continent. But Paul VI preferred to listen to the minority of prelates like Cardinal Joseph Malula who went on to design the Zaire Rite, a little-known addition to the list of Western liturgies. (255)

I would also like to have learned about the financial scandals allegedly regarding the Mafia, drug money, and the Vatican bank during the reign of Paul VI, but Chiron does not cover them.

Chiron’s biography greatly increased my understanding of Pope St. Paul VI. Before reading The Divided Pope, I was tempted to see Paul VI’s strong assertions of orthodoxy merely as a means of placating his critics. Now I am persuaded that he was acting out of genuine apostolic zeal (although critics will still point to his controversial opinions about ecumenism, religious liberty, and the social reign of Christ the King). Put differently, when Paul VI issued his Credo of the People of God in 1968, it seems to me that he meant it. This confession of faith not only includes a reaffirmation of the Christology and pneumatology of the earlier ecumenical Councils but several statements that reject modern indeterminacy. Consider the line, “The intellect which God has given us reaches that which is, and not merely the subjective expression of the structures and development of consciousness.”[4] Perhaps these words were added to correct his more liberal friends such as accused-Free Mason Cardinal Léon-Joseph Suenens, who inveighed not only against the Church’s “legalism” but its “essentialism.”

To his credit, Montini was not a Peronist, saying one thing to one crowd and the opposite to another merely in order to maintain control. With the exception of the aforementioned social doctrines, he strove to maintain the orthodoxy of the Church even as he ineptly presided over one of her worst doctrinal crises in history. His blind spots proved profoundly damaging. Paul VI took Pope John XXIII’s assertion that the teaching of the Church was one thing and its presentation another as an article of faith. Both would have done well to heed Marshall McLuhan’s insight that the medium is the message: you cannot usher in drastic changes to the medium and expect everyone to think that the message is the same. Or to say the same thing in a more theological key: you cannot change the law of prayer without affecting the law of belief.

As for Paul VI’s brand of ecumenism (which, judging by the number of converts to the Catholic Church it induced, was a complete failure), there is nothing wrong per se with being gentle to non-Catholics. Pope St. Gregory the Great, it is said,

extended his charity to the heretics, whom he sought to gain by mildness. He wrote to the bishop of Naples to receive and reconcile readily those who desired it, taking upon his own soul the danger, lest he should be charged with their perdition if they should perish by too great severity.[5]

Yet the same Pope “was careful not…to relax the severity of the law of God in the least tittle.”[6] Gregory did not give mixed signals. He did not give heretical bishops his old episcopal ring or kiss their feet, nor did he ask heretics for their advice on how to redesign the sacred liturgy in order to make it more amenable to their heretical beliefs.

Paul VI truly was the Divided Pope, and we have been living in the wake of his schizophrenia ever since. Chiron’s biography is an excellent place to begin to understand the divide.

This article originally appeared in The Latin Mass

magazine 32:2 (Summer 2023). Many thanks to its editors for allowing its publication here.

Notes

[1] See my review in Antiphon 23:3 (Fall 2019), 332-337.

[5] Alban Butler, The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, vol. 3 (Dublin: Duffy, 1845), 118.

[6] Ibid.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)