St Peter Martyr was killed on April 6, 1252, but since that day so often occurs in Holy Week or Easter week, when he was canonized less than a year after his death, his feast was assigned to April 29. As we have noted several times in the past (see here and here), his relics are in the Portinari chapel within the basilica of St Eustorgius in Milan. Here are some pictures and a video of the large reliquary containing his skull, taken in the basilica earlier today by Nicola de’ Grandi.

In the background of this picture, we see the Saint’s monumental tomb of the type known as an ‘arca’ in Italian, which is deliberately designed so that the faithful can walk under it and touch the sarcophagus containing the relics.Sunday, April 30, 2023

The Third Sunday after Easter

Gregory DiPippoOn this third Sunday, and on the two that follow before the Ascension, the Church exhorts us to rejoicing and exultation for the Resurrection and Ascension of Christ, wherefore the Introit of this Sunday begins, ‘Shout with joy to God, all the earth.’ And there follows Alleluia, because this shout of joy is the exultation which the mind has for eternal things, and is to be made only to God. There follows, ‘Sing a psalm to His name’, that is, praise him with cheerful work, and likewise there follows a single Alleluia, because all other things arise from a single root, which is charity. There follows, ‘Give glory to His praise’, and there follows at the end a triple Alleluia, because from the power of the Father, and the wisdom of the Son, and the goodness of the Holy Spirit does it come about that He delivered us through His Passion and Resurrection, and therefore is God to be praised. But although there is exultation, nevertheless fear is also inculcated, lest hope without fear grow wanton unto presumption. (William Durandus, Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, 6, 94, 1)

Introitus (Ps 65) Jubiláte Deo, omnis terra, allelúia: psalmum dícite nómini ejus, allelúja: date glóriam laudi ejus, allelúja, allelúja, allelúja. V. Dícite Deo, quam terribilia sunt ópera tua, Dómine! in multitúdine virtútis tuæ mentientur tibi inimíci tui. Glória Patri. Sicut erat. Jubiláte Deo.Introit Shout with joy to God, all the earth, alleluia, sing ye a psalm to His name, alleluia; give glory to His praise; alleluia, alleluia, alleluia. V. Say ye unto God, How terrible are thy works, o Lord! in the multitude of thy strength thy enemies shall lie to thee. Glory be to the Father... As it was in the beginning... Shout with joy to God...

This Psalm has in the title the inscription, ‘For the end, a song of a Psalm of Resurrection’. When you hear ‘for the end’ (in the titles of various Psalms), understand it to mean ‘for Christ’, as the Apostle says, ‘For the end of the law is Christ, for righteousness to every one that believeth.’ (Rom. 10,4) ... ‘Jubilate unto God every land.’ What is jubilate? Break forth unto the voice of rejoicings, if you cannot break forth into words. For jubilation is not of words, but the sound alone of men rejoicing is uttered, as of a heart laboring and bringing forth into voice the pleasure of a thing imagined which cannot be expressed. ... ‘Say ye to God, How to be feared are Your works!’ Wherefore to be feared and not to be loved? Hear another voice of a Psalm (2, 11): ‘Serve the Lord in fear, and exult unto Him with trembling.’ What does this mean? Hear the voice of the Apostle: ‘With fear, he says, and trembling, work out your own salvation.’ Wherefore with fear and trembling? He has also given the reason: for God it is that works in you both to will and to work according to good will. (Phil. 2, 12-13) If therefore God works in you, by the Grace of God you work well, not by your strength. (St Augustine, Treatise on Psalm 65. The term ‘a psalm of Resurrection’ is in the title of the Greek and Latin translations of the Psalter.)

Saturday, April 29, 2023

The Centenary of St Thérèse of Lisieux’s Beatification

Gregory DiPippoToday marks the centenary of the beatification of St Thérèse of Lisieux, who passed into eternal life on September 30, 1897. Pope Benedict XV permitted the opening of her cause in August of 1921, when less than half the traditional waiting period after a proposed Saint’s death (fifty years) had elapsed; Pius XI had the honor of beatifying her, and then of canonizing her just over two years later, in May of 1925.

Here is a video from the archives of the newsreel service British Pathé, which shows the laying of the cornerstone of the basilica built to honor Thérèse at Lisieux, in 1929. The bishop is H.E. Alexis-Armand Cardinal Charost, archbishop of Rennes. We also see her relics carried in procession on a massive palanquin. - Sancta Theresa, ora pro nobis!Friday, April 28, 2023

Undoing the Dismal: Liberating Sunday’s Soul

Michael P. FoleyOne of the recurring themes of the pontificate of Benedict XVI was the vital nature of Sunday. At the 2005 Eucharistic Congress, at the 2005 World Youth Day, and in a 2007 sermon in Vienna, the Pope repeated an arresting line from the acts of the martyrs. In A.D. 304, forty nine Christians were apprehended for assembling on Sunday, in violation of imperial law. When the Proconsul asked them “why on earth they had disobeyed the Emperor’s severe orders,” one of them, a man named Emeritus, replied: Sine dominico non possumus. [1] Emeritus’ response has been justifiably translated “Without Sunday we cannot live,” but its literal meaning is even more astonishing: “Without Sunday, we cannot exist.”

Thursday, April 27, 2023

Holy Thursday 2023 Photopost (Part 1)

Gregory DiPippoTwo Royal Psalters

Gregory DiPippoThe wooden covers are mounted with cabochons in metal frames, surrounding carved ivory plaques; the plaque on the front represents God protecting the soul of King David from various adversities. (Bibliothèque National de France, Département des Manuscrits, Latin 1152)

Wednesday, April 26, 2023

A Rogation Day Procession in Paris

Gregory DiPippoThe church of St Eugène in Paris always celebrates the liturgy in an exemplary fashion, and not only because our friends of the Schola Sainte Cécile are the in-house choir, and sing such beautiful music, always appropriately chosen for the liturgical day. The church also makes a great effort to preserve the best of the liturgical traditions of its city and nation, as, for example, in the celebration of Vespers on Easter according to the old medieval form, which we have highlighted previously. Yesterday offered another very good example of this; during the Rogation procession, they carried several relics, including a classic palanquin for a large reliquary.

The program of the entire ceremony (in Latin and French) can be seen here:

https://schola-sainte-cecile.com/programmes/2022-2023/09-sanctoral/04-25-Litanies-Majeures.pdf. There are three musical parts at the Mass which are also particularly worth noting.

- During the incensation at the Offertory (1:12:00), the choir sings one of the most ancient surviving liturgical texts of all, a litany composed by St Martin of Tours, and used in the ancient Gallican Rite. (Explained in greater detail in an article by Henri de Villiers, the head of the Schola.)

Posted Wednesday, April 26, 2023

Labels: Medieval Liturgy, Paris, Rogation Days, Schola Sainte Cécile

The Solemnity of St Joseph, Patron of the Universal Church 2023

Gregory DiPippo |

| St Joseph and the Infant Christ, by Juan Antonio Frias y Escalante, 1660-65 |

The feast of St Joseph, Patron of the Universal Church, was originally called “the Patronage of St Joseph,” and fixed to the Third Sunday after Easter. It was kept by a great many dioceses and religious orders, particularly promoted by the Carmelites, before it was extended to the universal Church by Bl. Pope Pius IX in 1847, and later granted an octave. When the custom of fixing feasts to particular Sundays was abolished as part of the Breviary reform of Pope St Pius X, it was anticipated to the previous Wednesday, the day of the week traditionally dedicated to Patron Saints. It was removed from the general Calendar in 1955 and replaced by the feast of St Joseph the Worker, one of the least fortunate aspects of the pre-Conciliar liturgical changes; the new feast itself was then downgraded from the highest of three grades (first class) in the 1962 Missal to the lowest of four (optional memorial) in 1970.

Tuesday, April 25, 2023

The Major Litanies in the Ambrosian Rite

Gregory DiPippoEven though the Ambrosian liturgy adopted this tradition from Rome, its liturgical texts for these days are rather more developed. Each of the four Rogation days has its own version of the Litany of the Saints; each of the three days of the Lesser Rogations has its own Mass, but on April 25th, the votive Mass “for penance” is said. I shall here give the liturgical texts for the Major Litanies, along with the rubrics for their public celebration, from an edition published by the Archdiocese of Milan in 1733.

After the celebration of the Mass of St Mark, the clergy and people gather at the cathedral, and proceed from there to the basilica of St Nabor, which by the 18th century was in the care of the Franciscans, and rededicated to their Patron Saint. The archbishop, wearing violet vestments, stands before the altar, and begins the rite with “Dominus vobiscum”, after which the archdeacon intones the following antiphon, which is continued by the choir.

| Domine Deus virtutum, Deus Is- rael, qui eduxisti populum tuum de terra Aegypti, et fecisti tibi nomen gloriae, peccavimus, im- pie egimus, iniquitatem fecimus; miserere nobis, Salvator mundi. |

O Lord God of hosts, God of Isra- el, who led Thy people out of the land of Egypt, and made for Thy- self a glorious name; we have sinned, we have done wickedly; we have wrought iniquity; have mercy on us, o Savior of the world. |

|

| An Ambrosian mazzeconico |

| Peccavimus ante te, Deus, ne des nos in opprobrium, propter nomen tuum, quia tu es Domi- nus, Deus noster, quem propiti- um exspectamus. |

We have sinned before Thee, o God, give us not unto reproach, for Thy name’s sake, for Thou are the Lord, our God, whom we await to show us mercy. |

| Misereris omnium Domine, et nihil odisti eorum quae fecisti, dissimulans peccata hominum propter paenitentiam, et parcens illis: quia tu es Dóminus, Deus noster. |

Thou hast mercy on all, O Lord, and hate none of the things which Thou hast made, overlooking the sins of men for the sake of repentance, and sparing them: because Thou art the Lord our God. |

|

Qui fecisti magnalia in Aegyp- to, mirabilia in terra Cham, ter- ribilia in Mari Rubro, non tra- das nos in manus gentium, nec dominentur nobis, qui oderunt nos. |

Thou who didst great things in Egypt, wondrous deeds in the land of Cham, terrible things at the Red Sea, deliver us not into the hands of the nations, nor let them rule over us that hate us. |

|

Circumdederunt nos mala, quo- rum non est numerus; da nobis auxilium de tribulatione; opera manuum tuarum ne despicias, Domine. |

Evils have surrounded us, that have no number; grant us help in our tribu- lation; despise not the works of Thy hands, o Lord. |

| Si fecissemus praecepta tua, Do- mine, habitassemus cum securi- tate et pace omni tempore vitae nostrae; nunc quoniam peccavi- mus, supervenerunt in nos om- nes tribulationes; pius es, Domi- ne, miserere nobis, et dona re- medium populo tuo, Deus Israel. |

If we had followed Thy precepts, o Lord, we would have dwelt in secur- ity and peace all the time of our life; now, because we have sinned, every tribulation has come upon us; holy art Thou, o Lord, have mercy on us, and give remedy, to Thy people, o God of Israel. |

| Iniquitates nostras agnoscimus, Domine; petimus deprecantes te, remitte nobis, Domine, peccata nostra. | We recognize our iniquities, o Lord, we ask Thee beseechingly; forgive us our sins, o Lord. |

| Vide, Domine, afflictionem po- puli tui, quoniam amara est ni- mis; humiliati enim sumus pro peccatis nostris; exaudi nos, qui es in caelis, quoniam non est alius praeter te, Domine. |

See the affliction of Thy people, o Lord, for it is exceedingly bitter, for we are laid low for our sins; hear us, Who art in heaven, for there is no other beside Thee, o Lord. |

|

Liberator noster de gentibus ira- cundis, ab insurgentibus in nos libera nos, Domine. |

Our deliverer from the wrathful nations, from them that rise up against us, deliver us, o Lord. |

On this day, after the Virgin Mary, the three Archangels are named, followed by the Apostles Peter, Paul, Andrew, and Mark, whose feast day it is; the martyrs Stephen, Felix, Fortunatus and Victor; then Pope Urban I, Tiburtius, Valerian and Cecilia. (The martyrdom of Cecilia, her betrothed Tiburtius, and his brother Valerian took place in the days of Pope Urban, 222-230; the brothers’ feast is on April 14.) There follows a group of bishops, including St Gregory, who instituted the Greater Rogations, St Satyrus, the brother of St Ambrose, then Galdinus, Charles Borromeo, and Ambrose, who always conclude the litanies in the Ambrosian Rite. The litany ends with three repetitions of “Exaudi, Christe. R. Voces nostras. Exaudi, Deus. R. Et miserere nobis.”, (Hear, o Christ, our voices. Hear o God, and have mercy on us.), and three Kyrie eleisons.

At the conclusion of the Litany, the archbishop sings the following Collect. “Omnipotens sempiterne Deus, cui sine fine potestas est miserendi, preces humilitatis nostrae placatus intende: ut quod delictorum nostrorum catena constringit, a tua nobis misericordia relaxetur. Per. – Almighty and everlasting God, that hast power without end to show mercy, be appeased and harken to the prayers of our low estate: so that what the chain of our sins bindeth may be loosed for us by Thy mercy.”

The deacon hebdomadary, the canon assigned to serve as deacon at the capitular services that week, then intones a responsory. (The Ambrosian Rite very frequently assigns specific chants to specific persons or groups within the chapter.)

R. Te deprecamur, Domine, * qui es misericors et pius, esto nobis propitius. V. Domine, exaudi orationem nostram, et clamor noster ad te perveniat. Qui es... – R. We beseech Thee, o Lord, * who art merciful and holy, be merciful unto us. V. O Lord, hear our prayer, and let our cry come unto Thee. Who art...

|

| The high altar of the church of St Victor. (Image from Wikipedia by Carlo dell’Orto; CC BY-SA 3.0) |

| Media vita in morte sumus; quem quærimus adjutórem, nisi te, Domine? qui pro peccatis nostris juste irásceris. Sancte Deus, Sancte fortis, Sancte misericors Salvator, amarae morti ne tradas nos. |

In the midst of life, we are in death; whom shall we seek to help us, if not Thee, o Lord, who art justly wroth for our sins. Holy God, holy mighty one, holy immortal one, hand us not over to bitter death. |

| Domine, inclina aurem tuam et audi; respice de caelo, et vide gemitum nostrum, et de manu mortis libera nos. |

O Lord, incline Thy ear, and hear; look down from heaven, and see our groaning, and deliver us from the hand of death. |

|

Exsurge, libera, Deus, de manu mortis, et ne infernus rapiat nos, ut leo, animas nostras. |

Arise, deliver our souls, God, from the hand of death, lest hell take us, like a lion. |

|

Cor nostrum conturbatum est, Domine, et formido mortis céci- dit super nos; ad tuam pietatem concurrimus: ne perdas pecca- tores, misericors. |

Our heart is troubled, o Lord, and the fear of death hath fallen upon us; we run to Thy mercy, destroy not the sinners, merciful one. |

|

Domine Deus, miserere, quia anni nostri in gemitibus consumati sunt, et mors furibunda succedit; Domine, libera nos. |

Lord God, have mercy, for our years are consumed in groaning, and furi- ous death cometh after; o Lord, de- liver us. |

At the altar of St Gregory, twelve Kyries are sung as above, followed by a second Litany of the Saints, shorter than the first one. The Saints named are the Virgin Mary, the Archangels, John the Baptist, the same Apostles as above, the martyrs Stephen, Saturninus, Savinus, Protus, Januarius, the bishops Martin and Gregory, Galdinus, Charles and Ambrose. This also concludes with a Collect, which specifically refers to St Gregory. “Infirmitatem nostram respice, omnipotens Deus, et quia pondus propriae actionis gravat, beati Gregorii Pontificis tui intercessio gloriosa nos protegat. Per. – Look upon our infirmity, almighty God, and since the weight of our actions beareth heavy upon us, may the glorious intercession of Thy bishop Gregory protect us.”

R. Rogamus te, Domine Deus, quia peccavimus tibi; veniam petimus, quam non meremur; * manum tuam porrige lapsis, qui latroni confitenti paradisi januas aperuisti. V. Vita nostra in dolore suspirat, et in opere non emendat, si exspectas, non corripimur, et si vindicas, non duramus. Manum tuam... – R. We beseech Thee, o Lord God, because we have sinned against Thee; we ask for forgiveness, which we do not deserve. * Stretch forth Thy hand to the fallen, Thou who didst open the doors of paradise to the thief that confessed. V. Our life suspireth in sorrow, and emendeth not in works; if Thou await us, we are not reproved, and if Thou take vengeance, we cannot endure it. Stretch forth...

Twelve Kyries are sung once again, followed by the Agnus Dei, alternated between the readers and the mazzeconici.

V. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

R. Gloria Patri. Sicut erat.

V. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

R. Sucipe deprecationem nostram, qui sedes ad dexteram Patris.

V. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

|

| St Charles Borromeo leading a procession with the relic of the Holy Nail during the great plague which struck Milan in 1576-7. St Gregory the Great originally introduced the Greater Rogations at Rome to beg God’s mercy and the end to a plague. (Painting by Giovan Mauro della Rovere, also known as ;“il Fiamminghino - the little Fleming”, since his father was born in Antwerp.) |

Catholic Education Foundation Seminar 2023: The Role of the Priest in Today’s Catholic School

David Clayton |

| St John Baptist de La Salle |

I am indebted, once again, to Fr Peter Stravinskas of the Catholic Education Foundation for the following information about this wonderful annual event intended primarily for bishops, priests and seminarians. I attended last year as a speaker and found it to be inspiring and full of hope. This offers practical advice and support priests who are involved in or have an interest in orthodox Catholic education. Here is the information that Fr Peter gave to me about this year’s conference.

The Catholic Education Foundation invites bishops, priests and seminarians to participate in an intensive and comprehensive three-day seminar The Role of the Priest in Today’s Catholic School.- Rev. Peter M. J. Stravinskas, Ph.D., S.T.D. (President, CEF)

- Michael Acquilano (Chief Operating Officer, Diocese of Charleston)

- Sister Elizabeth Ann Allen, OP, Ed.D. (Director, Center for Catholic Education, Aquinas College, Nashville)

- Rev. John Belmonte, SJ (Superintendent of Schools, Diocese of Venice)

- Rev. Robert-Charles Bengry (Pastor, Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, Calgary)

- David Bonagura (Regis High School, New York)

- Most Rev. Thomas Daly (Bishop of Spokane; Chairman, USCCB Committee on Education)

- Rev. Michael Davis (Pastor, Archdiocese of Miami)

- Mary Pat Donoghue (Executive Director, Secretariat of Catholic Education, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops)

- Julie Enzler (Principal, Cathedral High School, Houston/ Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter)

- Most Rev. Arthur Kennedy, Ph.D. (Auxiliary Bishop Emeritus, Archdiocese of Boston)

- Rev. James Kuroly, Ed.D. (President/Rector, Cathedral Prep, Brooklyn)

- Alexis Kutarna (Director of Sacred Music, Cathedral High School, Houston/ Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter)

- Dr. Sebastian Mahfood (President, En Route Books and Media)

- Dr. Gregory Monroe (Superintendent of Schools, Diocese of Charlotte)

- Rev. Christopher Peschel (Pastor & Central School Board, Diocese of Fall River)

- Brother Owen Sadlier, OSF (Professor of Philosophy, St. Joseph Seminary, Archdiocese of New York)

- Rev. Msgr. Joseph Schaedel (Pastor, Archdiocese of Indianapolis)

- Lincoln Synder (President, National Catholic Educational Association)

- Dr. Susan Trasancos (Vice-President of the Board, Chief Research Officer, Children of God for Life)

- Rev. Patrick York (Pastor, Diocese of Wichita)

Monday, April 24, 2023

An Advertising Specialist Diagnoses the Church’s Modern Communication Failure

Peter KwasniewskiWe—communication professionals—have found that there is a lot to thank you for, since all the working tools that we use today in communication were invented by religious people. If you don’t believe me, let’s consider it.

The first mass communication vehicle invented, the strongest of all, was the bell. The bell that had a message in its clanging reached, in the era of the villages, eighty or ninety per cent of the small towns. It not only reached the people but changed the physical and mental behavior of eighty, ninety per cent of the villages every time it rang, and spread its messages in a unique way. Before the bell came the town crier, who was nothing more than a very shabby direct mail.

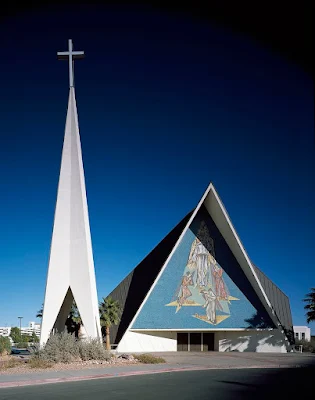

After this great vehicle of mass communication (continuing in this analogy of ours), you religious people invented a tool that communication uses a lot today: the display. We use displays to highlight information. When all the roofs of the villages were low, you built a very high roof, four or five times higher and in the shape of a spike, and this was not to make it easier for the snow to drop off the roof because you continued to follow this architectural design in places where there was no snow. This was so that the church tower could be seen in the distance as soon as you entered the village. By this display, we could easily locate the church.

More than this, you invented the first logo, the happiest of them all: the cross. The cross that no one ever forgot to put at the top of the display and that allowed not only its identification as a church, but also its belonging to a “brand,” to that specific religion, and not to a competing brand. You invented a rich logo like that—a logo so good that Hitler took it for himself, put four tails on it, and almost won the war with that logo.

You have invented still more things from the world of communication. Today, one of the most precious tools to use in campaigns—useful at the time of planning, in order to find the right text to say, to the right audience, at the right time—is research; without research, it is crazy to venture to say anything. The first known research department was invented by you: the confessional. The confessional, my mother still thinks, was made only for forgiveness; you religious people know that the confessional was invented to gather information. It was then a holy research department. I say holy because today, when we do any kind of research, it is possible that the person will lie to us; but in the holy research department the information was not only spontaneous, it was necessary and true. That is why the priest, in the era of the villages, was the major advisor, greater than the political advisor. There, in the nave of the church, at sermon time, you could shape the message to the main complaints of that week, give a word of comfort, a reassurance.

Then my mother, who didn’t know any of this, gets something very rewarding from her research department. For example, if I want to rebuild myself from the inside out, I go to an psychoanalyst, I pay a thousand dollars, and he helps me a little bit; but my mother goes to a confessional, she comes away rebuilt from the inside out, she comes away relieved and forgiven—something that no analyst can do, even if you pay twice as much. This by-product that the confessional gives my mother is very helpful for its clientele.

There is more to this whole communication machine that religious people have invented. We could say that the promotional event was also a religious invention; what, after all, is a procession that closes down a country town with a festival, if not a promotion for the day of Our Lady, a promotion for the day of St. George, etc.? A religious promotion! We do promotions that have much of what you have taught us: there is a banner, there is a flag, there are special clothes, there is a commercial mystique.

You have changed the system of the Mass. The Mass is no longer in Latin and the priest no longer has his back to the faithful. I have very bad news for you. My mother never thought that you had your back to her; she thought that you were facing God, and she liked Latin (although she didn’t understand the words well) because it was a mystical language that made you understand God. In my opinion, this change was a tremendous mistake.

But my point is that all this communication machinery that you invented was not for nothing. You didn’t invent bells and all that stuff, which I call religious packaging, just for nothing. No, you had the same problem that we have now: you had something to propagate, your product was called faith.

I have good news for you: this product, faith, is in short supply in the market. But today you no longer propagate faith; today what we see is much more the fights between bishops, the fights between you and the government, than the product you manufacture. Faith was what my mother used to go to church for. Today, all the trouble in the Church is like an ice-cream company that stops advertising ice cream and starts advertising the fights of the board of directors. This leads to nothing.

This reminds me of a little story I heard some time ago in the United States. There was a guy who had a store across the street from another store. He would put nylon stockings on sale at $1.50, and then the other would put the same stockings on sale for $1.35, but neither sold more stockings than the other. They weren’t going to sell any more anyway, so long as they were running both stores at the same time. [I take it the meaning here is that putting faith “on sale” at a cut rate, as the Church seemed to be doing after the council by dumbing things down and letting up on requirements, was not actually going to succeed in “selling” the product more than if the price had been kept higher.—PK]

It is up to the government to do the government’s job. I think that the product you manufacture is independent of the economic class of the customer.

I want to propose to you another line of reasoning. You don’t look favorably on the consumer society, but maybe you should see television as the bell of today, because your bell does not work anymore in the cities. A mere observer can see that your tower—the display of the spire—is now hidden among many other towers with red lights on top. The research of the confessional is deactivated because the clientele has not been renewed; you have no fresh audience. If by some chance the young people discover that they can live without the Church, then things will get really bad.

Your audience is divided into three segments. The ones who need faith first, even before food, are the sick, but this, fortunately, is a minority. The second market segment is the elderly, over seventy or whatever; they change their behavior, and start to want to have faith. But the huge contingent that maybe you are having a hard time reaching are children, youth, and adults who represent eighty to ninety per cent—this public is the one that is more or less difficult because you have to figure out how to talk to them, where, and when.

That is why I keep repeating that maybe television is the proper vehicle. In this country where everything is of heterogeneous distribution, the only thing in common that spreads in a bigger way in the country is mass communication, because my Silvio Santos [Brazilian tycoon and television host] is the same as the man in the periphery. If this is true, some action must be taken. Through communication, we receive things that fill a void. Playboy was very successful in the USA because it showed Americans exactly what they did not have. In the USA, TV series about doctors are also successful because it is very rare to have a private doctor there; this is called filling emptinesses through communication. And it is a great communication trick. Another communication trick is used in wrestling: there is an ugly guy and a handsome guy, and the ugly guy already creates an atmosphere of terror. We identify with the one who suffers, the handsome one who is always losing, until the moment he turns the game around. Most soap operas are more or less like this.

All of that is a parallel to illustrate a little bit the tricks of communication. What to do? No X-ray plate tells you what you should do; it just tells you how things are. Spreading faith is not simply praying a Mass at 8 a.m. on Globo [a TV channel]; it is selling a content called faith. Something that makes the client believe in what the Church can do for him.

There has been a reduction of ritual. Even in the Roman Catholic Church, they’ve translated the Mass out of the ritual language and into a language with domestic associations. The Latin of the Mass was a language that threw you out of the field of domesticity. The altar was turned around so that the priest’s back was to you, and with him you addressed yourself outward. Now they have turned the altar around and it looks like Julia Child giving a cooking demonstration—all homey and cozy… They have forgotten that the function of ritual is to pitch you out, not to wrap you back in where you have been all the time.Fr Dwight Longenecker commented as follows about the sad story of Campbell, which is the story of many others who left the Church for similar reasons:

Campbell was brought up as a Catholic, but after the second Vatican Council he left the Catholic Church in disgust. He had come to appreciate the power of myth with its ability to reach into the subconscious and connect with the deepest parts of the human personality. He also realized that the Catholic Church was the one religious body in the West that still maintained a ritual sacrificial system, a hierophantic priesthood and the ceremonies and rites of mystery. He understood how these rites were connected with and made applicable the truths and the symbols of myth.If the rulers of the Church will not respect tradition; will not hear the cries of the faithful; will not pay heed even to the secular professionals who are pointing out their folly; what—who—are they listening to, and why do they seem bent on doing everything that will undermine their “product”?

Then he said the Catholic Church went and threw it all out the window. Furthermore, they threw it out the window at exactly the time that it was needed most. He saw that America had been Protestantized and with Protestantism the religion of mystery, myth and ceremony that drew on the deepest recesses of the human imagination was emasculated. The ceremony was replaced with dull, literal Biblicism and the sacraments were replaced with a utilitarian, bland therapeutic Deism. The mysterious temples to the Divine Son of God were replaced with bare preaching halls devoid of symbol, devoid of art, devoid of beauty, devoid of the ancient faith.

Feeling abandoned by his own religion he abandoned the religion.

This story unlocks one of the most maddening and frustrating things about the Catholic Church in the twentieth century. At just the time when our culture needed the depth of Catholic worship, ritual, beauty, art and liturgy the Catholic Church went in the other direction. In an attempt to be up to date they were actually half a century too late.

Sunday, April 23, 2023

Good Shepherd Sunday 2023

Gregory DiPippo |

The Good Shepherd, by Cristóbal García Salmerón (1603-66), originally painted for the church of St Genesius in Arles, France, now in the Prado Museum in Madrid. (Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.)

|

In the Ambrosian Rite, the Gospel for today is St John’s account of the Baptism of Christ, chapter 1, 29-34, which the Roman Rite reads on the octave of Epiphany. In the oldest Ambrosian lectionary, the Gospels for the Sundays between Low Sunday and the Ascension continue the instruction of those who were baptized at Easter, and are centered on the figure of Christ. Today John calls him “the Lamb of God”, and on the following Sunday (John 1, 15-28), “the only-begotten Son who is in the bosom of the Father.” On the next two Sundays, Christ speaks of Himself as “the light of the world” (John 8, 12-20) and “the way, the truth and the light (John 14, 1-14).” In the Carolingian era, when the Ambrosian Rite underwent a significant Romanization, the latter three were replaced with the traditional Roman Gospels for these Sundays, but the Gospel of today remained; it is accompanied by the following particularly beautiful preface.

|

| John the Baptist Indicates the Lamb of God to Ss Peter and Andrew; fresco by Domenico Zampieri (1581-1641), generally known as Domenichino, in the ceiling of the apse of the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle in Rome, 1622-28. (Image by AlfvanBeem released to the public domain, from Wikimedia Commons.) |

Truly ... eternal God: Who made all the elements of the world, and arranged the various changes of time, and subjected to man, who was made in Thy image, all living things, and the wonders of creation. And though his origin is of earth, nonetheless, the life of heaven is conferred upon him in the regeneration of baptism. For then the author of death was conquered, he obtained the grace of immortality, and when the error of his transgression was broken, he found the way of truth. Through Christ...

In the Byzantine Rite, today is called the Sunday of the Myrrh-bearing Women from its Gospel, Mark 15, 43 – 16, 8. In the first part of this reading, Joseph of Arimathea requests from Pilate and receives the body of the Lord for burial, wraps Him in the shroud, and lays Him in the tomb; in the second (which the Roman Rite reads on Easter itself, minus the last verse), the women come to the tomb to anoint the body, and meet the angel who tells them that He has risen, and bids them go tell the disciples.

|

| A fresco of the Myrrh-Bearing Women in the Dionysiou Monastery on Mt Athos. |

At Vespers of the Sunday of the Myrrh-bearing Women, these same chants are sung at the end, but the first two change places, and the second and third have additions (marked here with *) which make them more appropriate for the Easter season.

When Thou went down to death, o immortal Life, then didst Thou slay Hades by the brightness of the Godhead; and when Thou raised up the dead from the netherworld, all the powers of heaven cried out, ‘Christ our God, Giver of life, glory to Thee.’ – Glory be.

The noble Joseph took down from the Cross Thy spotless Body, and when he had wrapped It in a clean shroud with spices, he laid It for burial in a new sepulchre; * but Thou didst rise on the third day, o Lord, granting great mercy to the world. – Now and ever.

The angel stood by the tomb and cried to the myrrh-bearing women, “Myrrh is fitting for the dead, but Christ has been shown free from corruption. * But cry out, ‘The Lord is risen, granting great mercy to the world!’ ”

This video includes only the first one, which has a rather more cheerful melody in its Paschal version.

Posted Sunday, April 23, 2023

Labels: Ambrosian Rite, Byzantine Liturgy, Good Shepherd Sunday, Roman Rite

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20Bihari,%20Sandor.jpg)