This year marks the tenth time we have run this series on the Lenten station churches in Rome! However, the professional circumstances of our dear friend Agnese, the original Roman pilgrim, have changed of late, such that she will likely be unable to attend many of them this time around. In past years, she has sometimes been joined in this series by other people; one of them, Mr Jacob Stein, whose work we have shared many times, will be providing most of the photos this year, as well as videos from his YouTube channel Crux Stationalis. We thank him for helping us to keep up one of our favorite Lenten traditions, and we are very pleased to begin this year’s series by wishing him a very happy birthday: ad multos annos, optime!

Tuesday, February 28, 2023

A Roman Pilgrim at the Station Churches 2023 (Part 1)

Gregory DiPippoDoes the Church Need Artists Who Are Humble Scribes? Or Original Geniuses?

David ClaytonLooking At Rabanus Maurus, St Dunstan, the anonymous painter of the San Damiano Crucifix, and Matthew Paris: how they are connected, and what they can teach us today.

Recently, I was put in touch with a small group of artists at the newly established sacred art studio at Ealing Abbey, the Benedictine house in West London. These artists are learning their craft under the guidance of the British iconographer Aidan Hart, and forming a group that learns together, and passes on what it learns to others, so as to encourage the spread of the iconographic tradition in the Roman Church.

I was interested in talking to them about their vision of past forms of iconography that might appeal to the modern eye, and so serve as a launch pad for what might in time be the development of a distinct contemporary, but nevertheless authentic, tradition of iconography in the Roman Church. I was very pleased to learn that they shared my enthusiasm for the line-based Romanesque and early Gothic styles of the English church. (Regular readers know that I tend to focus on the work of the 13th-century Gothic artist Matthew Paris.) The artists of the Ealing Abbey studio directed my attention to the work, previously unknown to me, of St Dunstan, who lived in the 10th century, a reformer of English monasticism who was based in Glastonbury for a large part of his life. He is less known as an artist: here is his drawing of Christ in which he has painted himself adoring the Saviour.The inscription above him reads: Dunstanum memet clemens rogo, Christe, tuere. Tenarias me non sinas sorbsisse procellas (I ask you, merciful Christ, to watch over me, Dunstan, and not let the Taenarian storms swallow me.)

In their book The Image of St Dunstan, Nigel Ramsay and Margaret Sparks suggest that the idea for placing himself in the image came to St Dunstan from a 9th-century manuscript by another monk, Rabanus Maurus. Maurus wrote and illuminated “De laudibus sanctae crucis - On the praises of the Holy Cross”, a collection of poems presenting the sacred symbol in words, images, and numbers. One of the illuminated poems (in which every line has the same number of letters) can be seen here: as we can see, Rabanus Maurus portrayed himself adoring the cross.

Another connection that occurred to me as I look at the St Dunstan image is that of the San Damiano crucifixion in the Basilica of St Claire in Assisi.

Monday, February 27, 2023

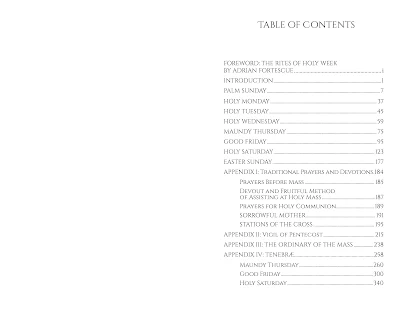

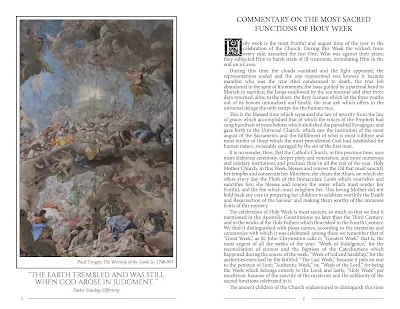

New Expanded Edition of Pre-55 Holy Week Congregational Book

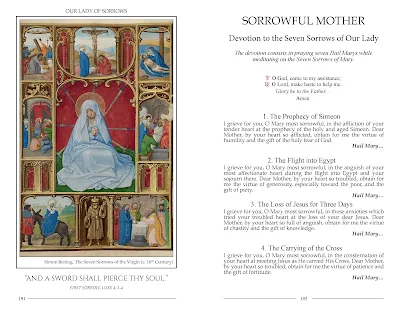

Peter KwasniewskiThe Second Edition now including the full text of the offices of Tenebrae for the Sacred Triduum, alongside other appendices for Stations of the Cross, the Seven Sorrows, and more.

Nearly 400 pages and with full-color illustrations, the book is quite comprehensive yet printed in a font that is easy to read — truly a book that can be used by congregations year after year.

The Second Edition is available from Roman Seraphic Books (www.romanseraphicbooks.com) at a reduced price from last year, down to $24.97 (from $28.97). International shipping options and bulk orders available.

Roman-Seraphic Books aspires, over time, to preserve and spread the traditional (pre-55) liturgical books, as well as the books pertinent to the Franciscan spiritual patrimony.

Books may be obtained here.

The restoration of tradition continues!

Lectio Divina (2): What, Where, and When

Peter KwasniewskiNaturally, questions arise. How do we decide, in practical terms, what to read each day—where to go in the Bible, how much, and for how long?

What we should bear in mind is that lectio divina is not meant to be an elaborate, burdensome obligation, but a childlike encounter with God in His Word, something that will refresh us and give us light for our journey. It will stretch us and challenge us, to be sure, but in such a way that we are still led to the peace of Christ. It’s not an academic study or a rote recitation. A personally fruitful lectio divina can be done by everybody.

I

First, as to quantity. Usually several verses, up to about half a chapter, is the right amount for people living in the world. A person could read an entire chapter, but that’s a lot to read slowly and meditatively, and it’s far more important to be able to ponder what we're reading and pray about it than to “get through” a certain book. Even one verse can furnish enough material for lectio divina, if the verse really hits one in the gut. The Gospels are ideally suited to lectio for many reasons, one of which is the way they are divided into small chunks or pericopes (e.g., a parable, miracle, or conversation) that can be taken by themselves.

It is important to read slowly, really thinking about what we are reading, and if something strikes us in a new way, or if we have a sense that this particular “word” (phrase or sentence) is what we need to take to heart, we should stop and ponder that word. There is no requirement to “finish” a section of the text; one can always resume there next time. On the whole, it will do us more good to meditate and pray than to continue reading. Indeed, our powers of concentration are limited, so even if we had all day at our disposal, we would do better with several shorter times of reading mixed with a variety of other activities.

The great Thomist Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange once stated:

One single sentence from Sacred Scripture can nourish the soul, illuminate it, strengthen it in adversity. Sacred Scripture is something far superior to a simple exposition of dogma, subdivided into special tracts: it is an ocean of revealed truth in which we can taste in advance the joys of eternal life.

II

Second, as to choice of text: there are 73 books in the Bible. They fall into groupings that are extremely different from one another, not only in genre—historical or narrative, prophetic, poetic, epistolary, legislative, apocalyptic—but also in their immediate accessibility or usefulness for personal prayer. The Fathers, Doctors, and mystics of the Church reached a level of spiritual maturity that enabled them to reap a harvest from any verse in Scripture, but since we are not their equals, we need to be more humble and more realistic. Some books clearly lend themselves to lectio divina for beginners, and indeed these books are the ones that all the saints keep going back to. They are: the Psalms (and the Wisdom literature in general); the prophets, both major and minor; and every book in the New Testament, with the Gospels holding pride of place. Simply put, if we choose one of the Gospels or a psalm, it is almost impossible not to profit from meditating on that reading.

Still, there will be dry moments when we can’t make heads or tails of a reading, and that’s also a healthy experience for us: we need to realize that we are not in charge. Any fruit we reap is God’s gift to us, and when we don’t seem to be reaping fruit, it’s because He’s preparing a larger harvest for us that demands a greater faith and trust in him before it can happen. The more experienced we become with lectio, the more freely we can launch out into the deep of other parts of Scripture and find nourishment there, as well.

III

Third, as to when and where: one need not do lectio divina in a church; what is necessary is to choose a time and place of quiet, where we can let our mind and heart go into the Word of God. For some people, this could be a conveniently situated church or chapel—it is one of the few places in our noisy world that is (usually) still recognized and respected as a haven of silence. But if there is a quiet place in one’s home early in the morning, that, too, would be well suited for lectio. Indeed, so great is the dignity of the Word of God that the Church has granted a plenary indulgence, with the usual conditions, to the devout reading of Scripture for one half-hour, anywhere.

The timing is also important: we need to find a time of day that is not so busy that we will be utterly distracted. For most people, this is early in the morning; once we get started with the work day, there’s too much going on. The morning has a special quality to it that strongly recommends it as a time for lectio.

We may conclude with the rousing words of the Benedictine monk Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel (c. 760–c. 840):

(Part II of a five-part series. Here is Part I.)For those who practice it, the experience of sacred reading sharpens perception, enriches understanding, rouses from sloth, banishes idleness, orders life, corrects bad habits, produces salutary weeping, and draws tears from contrite hearts . . . curbs idle speech and vanity, awakens longing for Christ and the heavenly fatherland.

It must always be accompanied by prayer and intimately joined with it, for we are cleansed by prayer and taught by reading. Therefore, whoever wishes to be with God at all times must prayer often and read often, for when we pray it is we who speak with God, but when we read it is God who speaks with us.

Every seeker of perfection advances in reading, prayer, and meditation. Reading enables us to learn what we do not know, meditation enables us to retain what we have learned, and prayer enables us to live what we have retained. Reading Sacred Scripture confers on us two gifts: it makes the soul’s understanding keener, and after snatching us from the world’s vanities, it leads us to the love of God.

Sunday, February 26, 2023

The First Sunday of Lent 2023

Gregory DiPippoHere is a very interesting recording of the Tract for the First Sunday of Lent by the French ensemble Dialogos, with only female voices. The verses Scapulis suis and Scuto circumdabit are omitted; at A sagitta, it veers off into some really nice polyphonic effects, and then resumes the Gregorian. The verses In manibus and Super aspidum are also omitted.

Tractus Qui hábitat in adjutorio Altíssimi, in protectióne Dei caeli commorábitur. V. Dicet Dómino: Susceptor meus es tu et refugium meum: Deus meus, sperábo in eum. V. Quoniam ipse liberávit me de láqueo venantium et a verbo áspero. V. Scápulis suis obumbrábit tibi, et sub pennis ejus sperábis. V. Scuto circúmdabit te véritas ejus: non timébis a timóre nocturno. V. A sagitta volante per diem, a negotio perambulante in ténebris, a ruína et daemonio meridiáno. V. Cadent a látere tuo mille, et decem milia a dextris tuis: tibi autem non appropinquábit. V. Quoniam Angelis suis mandávit de te, ut custodiant te in ómnibus viis tuis. V. In mánibus portábunt te, ne umquam offendas ad lápidem pedem tuum. V. Super áspidem et basiliscum ambulábis, et conculcábis leónem et dracónem. V. Quoniam in me sperávit, liberábo eum: prótegam eum, quoniam cognóvit nomen meum. V. Invocábit me, et ego exaudiam eum: cum ipso sum in tribulatióne. V. Eripiam eum et glorificábo eum: longitúdine diérum adimplébo eum, et ostendam illi salutáre meum.

While we’re at it, here’s a very good recording of the Gradual which precedes the Tract, with repetition of the first part, by the Consortium Vocale.

He hath given his angels charge over thee; to keep thee in all thy ways. V. In their hands they shall bear thee up: lest thou dash thy foot against a stone. (Psalm 90, 11-12)

Saturday, February 25, 2023

New Liturgical Anathemas for the Post-Conciliar Rite

Gregory DiPippo |

| The frontispiece of a Byzantine Catholic Rite archieratikon, the liturgy book containing the bishop’s parts of the major liturgies, printed at Supraśl, Poland in 1716. |

Sacred Music Workshop in Dickinson, North Dakota, April 14-15

Jennifer Donelson-NowickaPlease join us on April 14 and 15 at St. Wenceslaus Catholic Church in Dickinson, North Dakota, for a two-day workshop on sacred music, featuring Dr. Jennifer Donelson-Nowicka, Director of Sacred Music at St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo Park, California.

The workshop will feature:- Talks about the Church’s vision for sacred music and praying with sacred music

- Study of the Church's sacred music and liturgy

- Instruction in reading and singing Gregorian chant

- Sung liturgies

- Opportunities for confession and prayer

- Fellowship with area musicians

Friday, February 24, 2023

Singing for Pope Benedict XVI

Charles ColeIn 2019 the London Oratory Schola — which sings the 6pm Mass at the Oratory Church on Saturday evenings — was invited to Rome to sing at the canonisation of John Henry Newman. During the days we spent in Rome, we sang on a number of occasions, including the canonisation itself. However, the most memorable highlight was a private recital for the Pope Emeritus, Benedict XVI.

|

| The London Oratory Schola, Fr George Bowen, Charles Cole, Daniel Wright (headmaster) and Dominic Lynch with Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI |

I particularly remember two boys telling me later that they had been speaking to a young seminarian whose uncle, a priest, had been sent to Pakistan where he was executed for baptising a Muslim. His nephew was absolutely frank about the fact that it was very likely the same could happen to him when he, too, returned to Pakistan, yet he was absolutely at peace with the path he had chosen. It brought to mind the words of Saint Philip Neri to the newly ordained priests of the English College in Rome as they were sent back to an almost certain death in Tudor England: ‘Salvete Flores Martyrum’ (Hail, flowers of the martyrs).

At the end of dinner, the Rector of the Seminary gave a wonderful speech and invited the Schola Prefect and the Student Prefect of the Seminary to come forward and shake hands together as a sign of friendship between us. He went on to tell the boys that as they had some spare rooms, any of them who wished to remain and begin life as seminarians immediately were most welcome to do so — to much laughter. Finally, he announced to his students that the following day, the boys were going to be singing for Pope Benedict. The words were barely out of his mouth before the seminarians erupted with huge applause and cheering. As we all walked back down the Janiculum to our hotel, I remember one of the Oratory school staff remarking to me “It’s going to be hard to top that experience.”

|

| Walking from the Sistine Courtyard to the Vatican Garden |

|

| The Schola warming up in the Sistine Vestry |

It is never easy to sing outdoors as there is usually a lack of acoustic or resonance. However, we could feel the sound lifting upwards and carrying far across the garden. I wondered what the tourists high up on the dome of St Peter’s would make of it, as we were out of sight underneath the trees. Benedict turned to Father George Bowen, our school chaplain who was seated beside him, and repeated in wonder “Tutti ragazzi!“, they are all boys, amazed that even the Tenors and Basses were schoolboys, with no professional men. After these two pieces and wary of tiring the Pope Emeritus, I turned to Archbishop Gänswein and asked if we should sing more or draw to a close. Turning to Benedict he said “Holy Father, would you like to give the boys your blessing now?” “No!” came the surprising response, “I want to hear more singing!“ So we sang Byrd’s Haec dies.

|

| The Schola singing for Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI |

We bade him farewell and Archbishop Gänswein thanked me once again for bringing the choir. We walked back down the hill, elated, yet with a sense of sublime calm, leaving the small man in white sitting on the bench, gazing out serenely over the garden.

Charles Cole is Director of the London Oratory Schola (www.londonoratoryschola.com) This article was originally published in the February 2023 edition of the London Oratory Parish Magazine.

The Sunday of Orthodoxy

Gregory DiPippoAs we approach the First Sunday of Lent, we are happy to share this article by Fr Deacon Philip Gilbert on the Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy in the Byzantine tradition. Father Philip is a deacon of the Ukrainian Greco-Catholic Church; we have previously published his articles on the week preceding Great Lent, and on the first ceremony of Lent in the Byzantine Rite, Vespers of Forgiveness Sunday. We also published photographs and a video of his subdiaconal ordination in 2018.

We, having received the grace and strength of the Spirit, and having also the assistance and co-operation of your royal authority, have with one voice declared as piety and proclaimed as truth: that the sacred icons of our Lord Jesus Christ are to be had and retained, inasmuch as he was very man; also those which set forth what is historically narrated in the Gospels; and those which represent our undefiled Lady, the holy Mother of God; and likewise those of the Holy Angels (for they have manifested themselves in human form to those who were counted worthy of the vision of them), or of any of the Saints. [We have also decreed] that the brave deeds of the Saints be portrayed on tablets and on the walls, and upon the sacred vessels and vestments, as has been the custom of the holy Catholic Church of God from ancient times; which custom was regarded as having the force of law in the teaching both of those holy leaders who lived in the first ages of the Church, and also of their successors our reverend Fathers. [We have likewise decreed] that these images are to be reverenced (προσκυνεῖν), that is, salutations are to be offered to them. The reason for using the word is, that it has a two-fold signification. For κυνεῖν in the old Greek tongue signifies both to salute and to kiss. [3]

|

| A Greek icon of the late 14th or early 15th century, representing the restoration of the icons, with the Empress St Theodora, her young son Michael III, and the Father of the Second Council of Nicea. From the icon collection of the British Museum. |

Thursday, February 23, 2023

St Peter Damian on Liturgical Prayer

Gregory DiPippoHowever, even the darkest days of the Church’s history are not without their Saints. As France gave Her the abbey of Cluny, which was ruled by six Saints in a row over a 190 year period, to pave the way for reform, Italy saw a new flourishing of strict and reform-minded monastic orders in the 11th century, led by St Romuald, the founder of the Camaldolese Order, and St John Gualbert, the founder of the Vallombrosians. It was among these communities that Peter Damian was formed as a religious, and was called to serve as abbot of an important Camaldolese house at Fonte Avellana.

It is often darkest before the dawn; after the deposition of Benedict IX and the extremely brief (24 day) reign of Damasus II, the Papal throne was occupied by Leo IX (1049-54), an active and enthusiastic reformer, now canonized as a Saint. From this time, the reform party within the Church was very much in the ascendant, with St Peter Damian as one of its most powerful leaders and spokesmen. In 1057, Pope Stephen IX made him the Cardinal-Bishop of Ostia, to which office it then belonged to crown the Pope, but he was later released from this position at his own request by Pope Alexander II. He continued to serve as a Papal legate and ambassador, and to write a great deal by way of exhortation to the clergy at all levels to a stricter and more disciplined life. Two particularly famous example of his severity are his rebuke to the canons of Besançon in France for sitting down during the Divine Office (!), although he was willing to allow this during the lessons of Matins, and to the bishop of Florence for playing a game of chess.

|

King Otto IV of Brandenburg indulges in frivolity. (From the Codex Manesse, 1305-13; public domain image from Wikipedia)

|

It was addressed to a monk and hermit named Leo, who had written to St Peter to inquire whether he ought to say “The Lord be with you” and “Pray, lord, give the blessing” when saying the Divine Office alone in his cell. St Peter’s answer is argued at length and with great thoroughness, but what it really boils down to is “the liturgy is not about you.” Since it is the public prayer of the Church, which is made of many members and yet One in the Holy Spirit, the liturgy may rightly speak in the singular in choir (he cites Psalms such as “Incline to me Thy ear, o Lord” and “I will bless the Lord at all times”), and in the plural when celebrated by only one. He also notes, perhaps more persuasively, that a very large part of the Divine Office is said in the plural, invitatories such as “Come, let us worship the Lord”, hymns such as “Rising in the night let us all keep watch” etc.; so much, in fact, that to switch it to the singular in private prayer would mean to either omit most of it or mutilate it.

(Note: The man who bought the Papacy from Benedict IX was his godfather, an archpriest named John Gratian, who did so for the worthiest of motives, namely, to get Benedict out of the way; as Pope he was called Gregory VI. Although he was deposed for this act of simony, he was held in such high regard that almost 30 years later, when St Gregory VII was elected, certainly no laxist in matters of Church discipline, he chose his Papal name in John Gratian’s honor.)

Candlemas 2023 Photopost (Part 2)

Gregory DiPippoAs always, we are very grateful to all those who contributed these photos of recent Candlemas liturgies, a final look back at the beauty of the Christmas solemnities as we embark on the austerities of Lent. As with the previous post, we include two sets of pictures of Requiem Masses said for Pope Benedict XVI, one of which was said with the Requiem Mass of Mozart.

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

Liturgical Notes on Ash Wednesday

Gregory DiPippoNot long afterwards, however, perhaps by Gregory himself, the four days preceding the first Sunday were added to the fast to bring the number of days to exactly forty, the length of the fast kept by the Lord Himself, as well as by the prophets Moses and Elijah. This extension of Lent back to Ash Wednesday, which was once commonly known as “in capite jejunii – at the beginning of the fast”, is a proper custom of the Roman Rite, attested in the earliest Roman liturgical books of the century after St Gregory. It was copied by the Mozarabic liturgy, but never by the Ambrosian, and indeed, the Milanese traditionally make a point of eating meat on this day. In the Eastern rites, Great Lent begins on the Monday of the First Week, two days before the Roman Ash Wednesday.

|

The Gospel of the Transfiguration, Matthew 17, 1-9, is read on the Ember Saturday of Lent in reference to the forty-day fast of Christ, which is mentioned on the previous Sunday (Matthew 4, 1-11) and of the two Prophets who appeared alongside Him at the Transfiguration, Moses and Elijah, both of whom appear in the readings of Ember Wednesday. (Icon by Theophanes the Greek, early 15th century, now in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.)

|

The blessing and imposition of ashes was originally a rite for those who were assigned to do penance publicly during Lent for grave or notorious sins, an extremely ancient discipline and practice of the Church. The extension of this custom to all the faithful began in the later part of the 10th century, and was solidified by the end of the 11th, when Pope Urban II prescribed it at the Council of Benevento in 1091. The rite of “expelling” the public penitents from the church on Ash Wednesday, and receiving them back on Maundy Thursday, remained in the Pontifical for centuries after it had faded from use; another trace is the prayer “for the penitents” among the Preces said at Lauds and Vespers in penitential seasons. Many medieval uses also added a special commemoration of the public penitents to the suffrages of the Saints; in the Sarum Use, it was said as follows at Lauds:

Aña Convertímini ad me in toto corde vestro, in jejunio et fletu, et in planctu, dicit Dóminus.

V. Peccávimus cum pátribus nostris. R. Injuste égimus, iniquitátem fécimus.

Oratio Exaudi, quaesumus, Dómine, súpplicum preces, et confitentium tibi parce peccátis: ut páriter nobis indulgentiam tríbuas benignus, et pacem.

Aña Be ye turned to me with all your heart, in fasting, and in weeping, and in mourning, sayeth the Lord.

V. We have sinned with our fathers. R. We have acted unjustly, we have wrought iniquity.

Prayer Graciously hear, we beseech Thee, O Lord, the prayers of Thy supplicants, and pardon the sins of those who confess to Thee: that Thou may kindly grant us both pardon and peace.

In the Middle Ages, the Ash Wednesday ceremony generally included a procession as well. Historically, processions are regarded as penitential acts by nature; this is the reason why even those of Candlemas and the Rogations were traditionally done in penitential violet, although the Mass of the former and the season of the latter require white vestments. (See note below.)

In the year 1143, a canon of St Peter’s named Benedict wrote the following brief description of the Ash Wednesday ceremony in his treatise on the rituals of Rome and the Papal court, now known as the Ordo Romanus XI. “The ‘Collect’ (i.e. gathering is held) at St Anastasia, where the Pope comes with the whole curia; and there is he dressed, and all the other orders go up to the altar. There the Pope gives the ashes, and the primicerius sings with the schola the Antiphon Exaudi nos, Domine. When the (ritual at the Collect church) is finished, the Pope and all the others go bare-footed in a procession to Santa Sabina, followed by the primicerius with the schola, as they sing (the antiphon) Immutemur habitu. When they reach the church, the subdeacon lays aside the (processional) cross, and goes to the altar during the litany (of the Saints)… the Pope sings the Mass without the Kyrie, because of the Litany”, (i.e., it has already been sung at the end of the Litany.)

Later descriptions of this ceremony, such as the various recensions of the Ordinal of Innocent III (1198-1216), mention that the ashes were made at the church of St Anastasia by burning the palms left over from the previous year’s Palm Sunday, a common custom to this very day. During the Papal residence in Avignon, however, many long-standing traditions of the Papal court dropped out of use and were never revived; thus, the procession is not included in the pre-Tridentine Missal of the Roman Curia, the antecedent of the Missal of St Pius V.

|

A penitential procession led by St Gregory the Great, from the Très Riches Heures du Duc du Berry, by the Limbourg brothers, 1412-16.

|

.jpg)