One of Plato’s most important contributions to philosophy is the doctrine of Ideas, the notion that non-material abstractions, which he called “Ideas”, are eternal, and more real than things in the material world. To give a specific example, the abstraction “horseness” is, according to this doctrine, more real than material horses, and exists eternally in a world of Ideas; actual horses in this world merely participate in that abstraction. Plato would say that if a man who had never seen a horse and knew nothing about them were to see one, and then see another later on, he would immediately know them to be the same kind of thing, not because of their physical similarity (horses can, after all, vary greatly in size, shape and color), but because they both participate in the same Idea. (The larger point of this doctrine is that things more important than horses, such as Virtue and Truth, also exist as eternal Ideas, independently of the degree to which they are practiced or known.)

Aristotle, however, rejected this doctrine of his teacher, a difference which gave rise to the proverb, “Plato was my friend, but the truth is a better friend.” (This is loosely based on a passage of the Nicomachean Ethics, 1096a, 11-15, and often cited in Latin, “Amicus Plato, sed magis amica veritas.”) For Aristotle, ideas, that is, abstractions, are less real than the material objects from which they are abstracted; they exist only in our minds, not in an eternal world of Ideas, and if a certain kind of object were wholly unknown to man, there would be no idea of it. To return to the example given above, “horseness” is less real than horses, and exists only in the human mind. If there were no horses, or no minds to perceive them, there would be no idea of a horse.

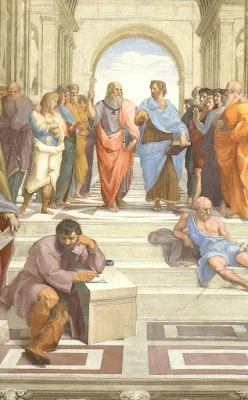

|

| The central section of Raphael’s School of Athens, with Plato and Aristotle highlighted by their position under the central arch. Plato, to the left, holds a copy of the Timaeus, and points up to the world of Ideas, while Aristotle on the right, holding the Ethics, gestures downward to the more real material world. (Plato is traditionally, but in all likelihood erroneously, said to be a portrait of Leonardo da Vinci; the figure writing at the desk was added later, and is believed by many scholars, with far greater probability, to be a portrait of Michelangelo. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons, cropped.) |

To give a specific example (unrelated to horses), Communism is an ideology; it assesses the world through notions about human nature and economics that have no relationship to reality, but exist only in the mind of communists. One of these notions, which would prove to be particularly catastrophic in the Soviet Union, was that one very large collective enterprise (say, a million acre farm) is better than many small enterprises (say, 1000 thousand-acre farms), because it will bring greater equality among the members of society. This was only true to the degree that it brought all the farmers on whom it was imposed to a roughly equal degree of poverty and misery.

The worst problem with assessing the world through such non-real notions is that they can render people permanently, and in some cases incurably, blind to reality. For example, there was no degree of failure of the Soviet economy, however catastrophic, and no degree of ensuing human misery, that could convince diehard members of the Communist Party that their ideology was a failure.

|

| Religious liberty in the workers’ paradise: agents of the Soviet state steal one of the bells of the cathedral of St Volodomyr in Kyiv, Ukraine, on January 5, 1930, the day before Christmas Eve on the Julian Calendar. (Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.) |

|

| The great renewal of the liturgy proceeds apace in the land of the Synodal Way... |

Likewise, there will come a day when the ideological conviction that the post-Conciliar reforms have been a spectacular success no longer holds the unreasonable fascination that it does on so many minds, especially among those who lived through them and remain unduly attached to the naïve optimism of their youth. Then the insults and forced resignations and suppressions will come to an end, and there will begin the difficult process of honestly assessing what went wrong, and why it went wrong, and determining what needs to be done to put it right.

It can be tiresome to wait for that to happen, but happen it always does, and in the meantime, as St Paul reminds us, “love beareth all things.” In Poland, it took ten years, and they were ten undeniably difficult years. But in Czechoslovakia, it took ten months, in East Germany, ten weeks, and in Romania, ten days.