Without doubt the most dolorous day of the Church’s annually recurring sanctification of time is Good Friday, the day on which she commemorates in a special manner the Passion and Death of Our Lord, the day that is the culmination of forty days of fasting and penance, and the only day of the year in the Latin rites of the Church on which her altars are deprived of the Holy Sacrifice.

But as Christian disciples who are sorrowful but always rejoicing (see 2 Cor. 6, 10), Good Friday is not an occasion of defeat but of love's triumph. Today, let us look at five good effects of this solemn, somber day.Friday, April 15, 2022

The Good Things of Good Friday

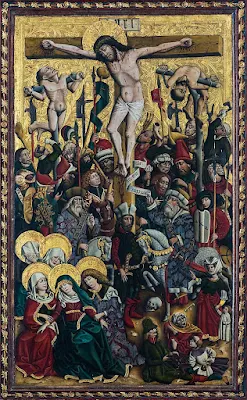

Michael P. FoleyAnonymous, Central Panel of the Knappenaltar, Hallstatt, Austria, 1450

1. Music

The liturgical observance of Good Friday has inspired not only a number of beautiful musical compositions but also a number of musical genres. The celebration of Tenebrae, the combination of Matins and Lauds during the pre-dawn mornings of Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, led to a body of music called Lamentations. The Matins of Tenebrae include several passages from the Book of Lamentations in the Old Testament. Jeremiah’s wrenching dirge over the destruction of Jerusalem was traditionally chanted, but beginning in the fifteenth century it became the inspiration for non-liturgical polyphonic settings by several famous composers. These Lamentations are recognized today as among the finest examples of Renaissance and Elizabethan music.

The Three Hours’ Devotion, or “Seven Last Words of Christ,” is a Good Friday service begun by Father Alphonso Messia, S.J., in 1732. From its place of origin in Lima, Peru, it quickly spread to all other countries in Central and South America and from there to Italy, England, and America, where both Catholics and Protestants enthusiastically embraced the devotion. The service, which alternates between homilies on the seven last statements of the crucified Christ and various hymns and prayers, has also inspired the composition of memorable music, including “The Seven Last Words of Christ” by Franz Josef Haydn (1787), “Les Sept Paroles de Notre Seigneur Jesus-Christ sur la Croix” by Charles Gounod (1855), and “Les sept paroles du Christ” by Theodore Dubois (1867).

Lastly, the Gospel readings of the traditional Roman rite backhandedly led to the creation of Passion Music. In the Roman calendar, all four Gospel narratives of the Lord’s Passion are read at a time during Holy Week: the Passion according to St. Matthew on Palm Sunday, the Passion according to St. Mark on the following Tuesday, the Passion according to St. Luke on Spy Wednesday, and the Passion according to St. John on Good Friday. During a High Mass, these narratives would be chanted by three clerics: a tenor taking the role of the narrator, a high tenor taking the role of the mob and various individuals, and a bass voice taking the role of Christ.

The music for these parts is an outstanding example of the power and beauty of Gregorian chant; understandably, then, it left a deep impression on the Western imagination even after the Protestant Reformation in large part did away with the liturgical setting of Holy Week. Nature abhorring a vacuum, Protestant composers soon began writing passion oratorios to replace the music of solemn liturgy, the most famous of which are J. S. Bach’s “Saint John Passion” and “Saint Matthew Passion.”[1]

2. Food

Good Friday is principally known as a day of fasting. In contemporary Church discipline, it is only one of the two mandatory days of fasting left on the calendar (Ash Wednesday being the other). In former times, it was the occasion of far more rigorous fasting. The Irish and other Catholics kept what was known as the Black Fast, in which nothing was consumed, except perhaps for a little water or plain tea, until sundown. And in the second century the early Church is said to have kept a forty-hour fast that began at the hour when Christ died on the Cross (3 p.m. Friday) and ended on the hour that He rose from the dead (7 a.m. Sunday).[2]

But despite its link to fasting, Good Friday is also associated with several foods. In Greece it is customary to have a dish with vinegar added to it, in honor of the gall our Lord drank on the Cross.[3] In some parts of Germany, one would only eat dumplings and stewed fruit.[4] In other areas of central Europe, vegetable soup and bread would be eaten at noon, and cheese with bread in the evening. At both meals people would eat standing and in silence.[5]

The widespread custom in Catholic countries of marking every new loaf of bread with the sign of the cross took on a special meaning on Good Friday. In Austria, for instance, Karfreitaglaib, bread with a cross imprinted on it, was eaten on this day.

But the most famous Good Friday bread is the hot cross bun. According to legend Father Rocliff, the priest in charge of distributing bread to the poor at St. Alban’s Abbey in Hertfordshire, decided on Good Friday in 1361 to decorate buns with a cross in honor of Our Lord’s Passion. The custom spread throughout the country and endured well into the nineteenth century, where it was sold on the streets of England, as the nursery rhyme tells us, for “one a penny, two a penny.” Today, hot cross buns are available during all of Lent.

Several pious superstations also grew around the hot cross bun, such as the belief that it would never grow moldy and that two antagonists would be reconciled if they shared one. Good Friday hot cross buns were kept throughout the year for its curative properties; if someone “fell ill, a little of the bun was grated into water and given to the sick person to aid his recovery.” Some folks believed that eating them on Good Friday would protect your home from fire, while others wore them “as charms against disease, lightning, and shipwreck”![7]

3. Customs

Besides the lore surrounding hot cross buns, Good Friday became a magnet for an assortment of non-liturgical customs and folk beliefs. In Mexico and other lands, piñatas in the likeness of Judas Iscariot would be beaten to a pulp.[8] In Europe, people refrained from all forms of merriment: no joking and laughing, no noisy tasks, no theatrical performances (except for Passion plays), no dancing and, as we shall see, no hunting. Even children “abstain[ed] from their usual games.”[9]

In the Middle Ages it was common for the population to wear black during all of Holy Week as a sign of mourning and especially on Good Friday, and it was Church law until 1642 to refrain from all servile labor during the Triduum. Schools, businesses, law courts, and government offices would all close during Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. In Catholic countries it was common for pardons to be granted to prisoners during Holy Week, and often charges would be dismissed in court in honor of our Lord’s Sacrifice.[10]

The list of what could and could not be done was often inspired by the events of the Passion. It was auspicious to plant and to garden on Good Friday because “Christ blessed and sanctified the soil by His burial,”[11] but woe to the man who swung a hammer or drove a nail on the day that these objects became instruments of Our Lord’s torture. Doing laundry was also verboten, as Christ’s clothes were stained with blood during His Passion. According to one superstition, any woman who did the washing on Good Friday would find the clothes spotted with blood and bad luck would follow her all the year. It was, however, good luck to die on Good Friday, since one’s soul would, like the Good Thief’s, be given speedy access to Heaven.

Georges Seurat, "The Gardener," 1882-1883

Among the non-superstitious customs, one of the most impressive can be found in the Eastern rites of the Christian Syrians and Chaldeans. Their customary greeting, Schlama or “Peace be with you,” is not used on Good Friday and Holy Saturday because it is the signature salutation of Christ after His resurrection (see Lk. 24,36; Jn. 20,21; 20,26) and is redolent of Judas’ perfidious greeting. Instead, they say “the Light of God be with your departed ones.”[12]

And, of course, the Western and Eastern rites of the Church developed beautiful liturgical and para-liturgical traditions for this unique anniversary. In the traditional Roman rite, the liturgical ministers vest in black as they would for a Requiem Mass. The service consists of the Mass of the Catechumens, where several readings, including the Passion according to St. John, are proclaimed; the Oratio Fidelium or “Prayer of the Faithful,” in which the Church solemnly prays for the world in a series of moving petitions; the Adoration of the Cross, when the priest unveils a crucifix in three stages and the people venerate the Cross with a kiss; and finally, the Mass of the Presanctified, a communion rite involving Hosts consecrated from a previous day.

Before the nineteenth century, the Good Friday service was supplemented throughout Europe by great processions through the streets that featured images of the suffering Christ and dolorous Blessed Virgin Mary borne on decorated platforms. This custom is still maintained today in the Latin countries of both the New and Old Worlds. Other popular or once-popular devotions include the Forty Hours’ Devotion, the Three Hours’ Devotion (see above), and the Stations of the Cross, the latter often dramatized (in Hispanic communities) outdoors.

Good Friday procession of the epitaphios in Greece

The most striking feature of the Good Friday service in the Byzantine Rite, on the other hand, is the “burial service” of Our Lord, where the faithful mourn the death of their Savior in a kind of funeral procession. A large and usually ornate shroud called an epitaphios bears Christ’s image and is carried around the perimeter of the church before it is placed in a Sepulchre. In addition to the Procession of the Holy Shroud, twelve Gospels are chanted, and a number of litanies are prayed, and a watch is kept at the Sepulchre.

4. Holy Deaths

The Catholic hagiographical tradition also cherishes the memory of several saints whose birthday into eternal bliss occurred on the anniversary of Our Lord’s death. Often, their feast days are transferred to another date; still, the day on which they died is a significant part of their life’s story.

Saints Azades, Tharba, and thousands of other Persian martyrs were cut down in a brutal persecution that began at twelve noon on Good Friday in A.D. 341 and ended on Low Sunday of the same year. Azades was a eunuch favored by the king; when he was martyred, the aggrieved tyrant limited the persecution to bishops, priests, monks, and nuns. Tharba, on the other hand, was a beautiful consecrated virgin who preferred being sawn in half to the lascivious advances of her judges. Their feast day is April 22.[13]

Matthias Stom, "Saint Ambrose," 1633-1639

Saint Ambrose of Milan (d. 397) is one of the great Latin doctors of the Church and the bishop who facilitated the conversion of Saint Augustine of Hippo.

Ambrose prayed during his final hours on Good Friday with his arms outstretched in imitation of his crucified Master and passed away shortly after receiving the Viaticum. His feast day is kept on December 7, the anniversary of his episcopal ordination.

Saint Proterius was a Patriarch of Alexandria who was stabbed to death in 557 by Eutychian schismatics in a baptistery where he had taken sanctuary. After killing him, the schismatics “dragged his dead body through the whole city, cut it in pieces, burnt it and scattered the ashes in the air.” His feast day is February 28.[14]

Saint Walter of Pontoise was an Abbot of St. Martin’s near Pontoise, France. He so feared becoming vainglorious from ruling a monastery that he frequently ran away from it. Eventually the Pope had to order him to remain in his abbey. Saint Walter was beaten and imprisoned by his fellow Benedictines for his opposition to simony within the order, but he bore his persecution with patience and even joy. He passed away on April 8, 1099, and his feast day remains on that day.[15]

Saint Francis of Paola, founder of the Minim Friars, sensed at the age of ninety-one that his death was approaching. Gathering his disciples and giving them his final instructions, he died on Good Friday in 1507 while listening to the reading of the Passion according to St. John. His feast is kept on April 2, the day that he passed away. Fifty-five years later, when his tomb was desecrated by the Huguenots, the saint’s body was discovered to be incorrupt. Nevertheless, the Huguenots dragged it out and burned it.[16]

Saint Margaret Clitherow, also known as the “Pearl of York,” is one of the forty great English recusant martyrs canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970. Arrested for giving Catholic priests safe harbor, she refused to plead on the grounds that her young children could then be tortured and forced to testify. Consequently, Margaret received the standard punishment for those who refused to plead: she was stripped and crushed to death by an immense weight. The two sergeants who were put in charge of her execution could not bring themselves to do it and hired four beggars instead. After her execution, even the ruthless Queen Elizabeth I wrote to the citizens of York to express her horror at St. Margaret’s death, who as a woman should not have received capital punishment. Her feast day is August 30.

Saint John Baptist de la Salle is the founder of the Christian Brothers and the patron saint of teachers; because of the vast educational reforms he instituted, he is also considered the father of modern pedagogy. To meet the dire educational and social needs of his day, this holy priest proposed the radical idea of popular free schools. Among his reforms was a focus on reading and the teaching of elementary-school children in the vernacular rather than Latin. During Holy Week of 1719, Saint Jean Baptiste sensed that his life was coming to an end. On Holy Thursday he blessed the brothers who had gathered at his bedside, and on Good Friday “he breathed his soul into the hand of his Creator.”[17] His feast is celebrated on May 15.

After decades of teaching small children and caring for the sick and elderly, the Servant of God Maria Luisa Godeau Leal founded the Augustinians of Our Lady of Help and took the religious name Maria of the Eucharist and of the Holy Spirit. Maria, who hailed from Mexico City, died on Good Friday, March 31, 1956. Her cause is currently being put forth for canonization.

Lastly, mention should be made of St. Veronica Giuliani who, although she did not pass away on Good Friday, led a life that was punctuated by this holy day. Veronica was a Poor Clare Abbess, mystic, and stigmatist. When only eighteen months old, she uttered her first words in response to a shopkeeper who was doling out a false measure of oil: “Do justice, God sees you.”[18] She had the privilege of receiving divine communications from the age of three, and loved the poor so much that she often gave them the clothes off her back. When she was four, “her dying mother entrusted each of her five children to a sacred wound of Christ”: Veronica was assigned the wound in Christ’s side.[19]

After becoming a nun of the Poor Clares, she desired to become united with Christ in His sufferings. Eventually, she was favored with the stigmata in the form of the Crown of Thorns, which left wounds that were painful and permanent. And on Good Friday in 1697, she received the impression of the wounds on Christ’s hands, feet, and side. After her death an autopsy was performed and it was discovered that on her heart were recognizable symbols of Christ’s Passion. Her body, which was laid to rest in her monastery at Citta del Castello, remained incorrupt until it was destroyed by a flood from the Tiber River.

5. Conversions

Good Friday is also auspicious for the living as well as for the dying. A number of sinners became saints, or at least embarked on the path to sanctification, because of this liturgical anniversary. Two of these saints had a conversion experience while hunting. Both Saint Eustace (a Roman martyr) and Saint Hubert (a medieval confessor Bishop of Germany) are said to have been irreverently using the day on which Our Lord’s blood was shed for us in an attempt to shed an animal’s blood for sport when they came upon a stag with a glowing cross between its large antlers. In Hubert’s case, the stunned hunter fell to his knees and heard a voice say to him, “Hubert, unless thou turnest to the Lord and leadest a holy life, thou shalt quickly go down to hell.” Hubert heeded the warning, eventually becoming the wise and holy bishop of Maastricht. And the image of a stag with a cross between its antlers eventually appeared on the label of the strong German liqueur named Jägermeister, or “master of the hunt.”

Robert Leighton, "Saint Hubert," 1911

But perhaps the most powerful conversion story involving Good Friday is the life of Saint John Gualbert (d. 1073). Saint John was an Italian nobleman whose only brother was murdered by a man that was supposed to have been his brother’s friend. Swearing revenge, John chanced to come upon him face to face in a narrow passageway on Good Friday. When he drew his sword to slay the murderer, the man dismounted his horse, knelt down, and “besought him by the passion of Jesus Christ, who suffered on that day, to spare his life.” The memory of Christ, who prayed for his murderers on the cross, greatly affected Saint John, and lifting his brother’s killer from the ground, said to him: “I can refuse nothing that is asked of me for the sake of Jesus Christ. I not only give you your life, but also my friendship for ever. Pray for me that God may pardon me my sin.”[21]

Anonymous, "St. John Gualbert," 14th century

John then went to a nearby monastery to pray, and as he knelt before the crucifix begging forgiveness for his sins, Christ on the cross bowed his head three times, signaling (as Saint John interpreted it) that He was pleased with his repentance. John immediately asked the Abbot to be admitted as a monk. Although the Abbot was apprehensive of John’s father, who was shocked by his son’s decision, John eventually became an exemplary monk and the founder of his own religious community at Vallis Umbrosa in Italy.

Conclusion

Scholars remain uncertain about the precise origins of the English name “Good Friday.” Is it like the Dutch term Goede Vrijdag that means the same thing, or is it, as others have speculated, a corruption of “God’s Friday”? Either way, we can see how God’s Friday of merciful self-giving, and the Church’s annual remembrance of it, have created an abundance of good things both little and great.

This article, which first appeared in the Winter/Spring 2013 issue of The Latin Mass magazine, has been since updated. Many thanks to the editors of TLM for allowing its publication here.

Notes

[1] Francis X. Weiser, S.J., Handbook of Christian Feasts and Customs (Harcourt, Brace & World, 1958), 191, 203–204.

[2] Weiser, Handbook, 201.

[3] Evelyn Vitz, A Continual Feast (Ignatius Press, 1985),190.

[4] Katherine Burton and Helmut Ripperger, Feast Day Cookbook (Catholic Authors Press, 2005), 53.

[5] Weiser, Handbook, 205.

[6] Burton, Feast Day Cookbook, 52.

[7] Weiser, Handbook, 206.

[8] See Wendy Devlin, “History of the Piñata,” Mexico Connect, http://www.mexconnect.com/mex_/travel/wdevlin/wdpinatahistory.html; Olga Rosino, Belinda Mendoza, and Christine Castro, “Piñatas!” http://www.epcc.edu/ftp/Homes/monicaw/borderlands/10_pi%C3%B1atas.htm.

[9] Weiser, Handbook, 205.

[10] Weiser, Handbook, 187.

[11] Weiser, Handbook, 205.

[12] Weiser, Handbook, 205.

[13] Alban Butler, The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Principal Saints, 1866 edition, accessible at bartleby.com.

[14] Butler, Lives.

[15] Butler, Lives.

[16] Lawrence Hess, “St. Francis of Paula,” Catholic Encyclopedia, 1909, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06231a.htm.

[17] Matthias Graham, “St. John Baptist de La Salle,” Catholic Encyclopedia, 1910, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08444a.htm.

[18] Lawrence Hess, “St. Veronica Giuliani,” Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15363a.htm.

[19] Joan Carroll Cruz, The Incorruptibles (TAN Books 1977), 252.

[20] “Nov. 3,” Faith & Family (Winter 2002), 42.

[21] Butler, Lives.

More recent articles:

Pope Leo XIVGregory DiPippo

Today, the Sacred College of Cardinals elected His Eminence Robert Cardinal Prevost, hitherto Prefect of the Dicastery for Bishops, as the 267th Pope and bishop of Rome; His Holiness has taken the name Leo XIV. He is the first American Pope, a native of Chicago, Illinois; he became a member of the Order of St Augustine in 1977, and served as the su...

The Basilica of St Victor in MilanGregory DiPippo

The church of Milan today celebrates the feast of the martyr St Victor, a Christian soldier from the Roman province of Africa, who was killed in the first year of the persecution of Diocletian, 303 AD, while serving at Milan under the Emperor Maximian. He is usually called “Maurus - the Moor” to distinguish him from the innumerable other Saints ca...

The Solemnity of St Joseph, Patron of the Universal Church 2025Gregory DiPippo

From the Encyclical Quamquam pluries of Pope Leo XIII on St Joseph, issued on the feast of the Assumption in 1889. It is providential that the conclave to elect a new pope should begin on this important solemnity; let us remember to count Joseph especially among the Saints to whom we address our prayers for a good outcome of this election. The spe...

Why the Traditional Mass Should Remain In LatinPeter Kwasniewski

In spite of attempts to suppress it, the traditional Latin Mass is here to stay. It may not be as widespread as it was in the halcyon days of Summorum Pontificum, but neither is it exactly hidden under a bushel, as the early Christians were during the Roman persecutions. In many cites, gigantic parishes run by former Ecclesia Dei institutes are pac...

An Illuminated Manuscript of St John’s ApocalypseGregory DiPippo

In honor of the feast of St John at the Latin Gate, here is a very beautiful illuminated manuscript which I stumbled across on the website of the Bibliothèque national de France (Département des Manuscrits, Néerlandais 3), made 1400. It contains the book of the Apocalypse in a Flemish translation, with an elaborately decorated page before each chap...

Gregorian Chant Courses This Summer at Clear Creek Abbey Gregory DiPippo

Clear Creek Abbey in northwest Oklahoma (diocese of Tulsa: located at 5804 W Monastery Road in Hulbert) will once again be hosting a week-long instruction in Gregorian chant, based on the course called Laus in Ecclesia, from Monday, July 14, to Friday, July 18. The course will be offered at three different levels of instruction:1) Gregorian initiat...

The Feast of St Vincent FerrerGregory DiPippo

The feast of St Vincent Ferrer was traditionally assigned to the day of his death, April 5th, but I say “assigned to” instead of “kept on” advisedly; that date falls within either Holy Week or Easter week so often that its was either translated or omitted more than it was celebrated on its proper day. [1] For this reason, in 2001 the Dominicans mov...

Good Shepherd Sunday 2025Gregory DiPippo

Dearest brethren, Christ suffered for us, leaving you an example that you should follow His steps; Who did no sin, neither was guile found in His mouth; Who, when He was reviled, did not revile. When He suffered, he threatened not, but delivered Himself to him that judged Him unjustly; Who His own self bore our sins in His body upon the tree: that...

The Gospel of Nicodemus in the Liturgy of EastertideGregory DiPippo

By “the Gospel of Nicodemus”, I mean not the apocryphal gospel of that title, but the passage of St John’s Gospel in which Christ speaks to Nicodemus, chapter 3, verses 1-21. This passage has an interesting and complex history among the readings of the Easter season. For liturgical use, the Roman Rite divides it into two parts, the second of which...

“The Angel Cried Out” - The Byzantine Easter Hymn to the Virgin MaryGregory DiPippo

In the Byzantine Divine Liturgy, there are several places where the priest sings a part of the anaphora out loud, and the choir makes a response, while he continues the anaphora silently. In the liturgy of St John Chrysostom, which is by far the more commonly used of the two anaphoras, the priest commemorates the Saints after the consecration and ...