Praesta, quæsumus, Domine: ut, sicut nos sanctorum Martyrum tuorum Naboris et Felicis natalitia celebranda non deserunt; ita jugiter suffragiis comitentur. Per Dominum... [Grant, we beseech Thee, O Lord, that just as the celebration of the birth of Thy holy Martyrs Nabor and Felix never abandons us, so may they always accompany us by their prayers. Through our Lord…]Nearly every time I post a comment in praise of a “lesser” saint’s feast on the traditional Roman calendar for the Mass, or publish a blog article along those lines, inevitably several comments arise: “We should get rid of a lot of these obscure or territorial saints and leave more room for more local or modern saints.” The ones who make these comments love the traditional liturgy, but they seem to agree with the rationale that led to the removal of over 300 saints from the general calendar in 1969.

I would like to suggest, in all kindness, that this gigantic overhaul was excessive, disproportionate, harmful, and uncharacteristic of liturgical history, which tends to prune rather than to purge, and which prefers to add more than to cut away. Yes, I’m quite aware that St. Pius V removed quite a few saints from the Roman calendar, but even his cuts could not compare with Paul VI’s — and besides, his successors pretty quickly began adding back ones that Pius had removed.

A university student once wrote the following note to me:

In my liturgy class, we discussed the calendar. What you wrote at Rorate about St. Felix of Valois — “Who is this obscure saint, and why is he cluttering our calendar?” — was the exact mindset the professor strove to pound into students’ minds that day. He described how over the centuries, “certain elements crept into the calendar” (his words), and these elements had clouded over the meaning of Sunday, plus many saints and feasts days held no meaning for us anymore and sometimes were mythological. But, he said, as if to clinch his point, “other popes have cleaned out the calendar before.”

Thank you for being willing to defend the old calendar and its rich sanctoral cycle and prayers. Any time I’ve tried to defend the beauty of the traditional rites in class, the things I’ve pointed to have been declared “unnecessary for modern man.” Well, to that I respond, the Mass should not have changed for modern man; modern man should have changed for the Mass.

That’s what all the modern liturgists said and still say: “The calendar was too cluttered, it needed a lot of pruning.” I used to think so, too — until I got to know the traditional missal well, over years of daily Massgoing, and came to love the richly-encrusted cycle of saints, famous and obscure, ancient and modern, and how they crowd into certain clusters, sometimes even forming “octaves” of a sort.

My appreciation of the density of the old calendar grew still more when I began attending Mass with the Institute of Christ the King, whose clergy follow (somewhat inconsistently, but with growing conviction) a sanctoral calendar of circa 1948. In this calendar there are even more saints, and frequently double commemorations. I have to say: so far from seeming cluttered, it’s like a big Catholic family with kids all over the place, and everyone happy. The multiple orations enrich the liturgy’s prayerfulness and power, rather than detracting from a “simplicity” or “focus” conceived in rationalist terms. Anyone who knows great works of art knows that they achieve their cumulative effect through multiple simultaneous means, and that unity and coherence are not foreign to but actually reliant upon a carefully balanced harmony of many parts, including tiny and seemingly insignificant details. Multiplicity and complexity are not the problem; pointless multiplication and a random or confused complexity are the problem.

I am reminded of the insight of Martin Mosebach:

It was the new Western way of perceiving the “real” sacred act as narrowed down to the consecration that handed over the Mass to the planners’ clutches. But liturgy has this in common with art: within its sphere there is no distinction between the important and the unimportant. All parts of a painting by a master are of equal significance, none can be dispensed with. Just imagine, in regard to Raphael’s painting of St. Cecilia, wanting only to recognize the value of the face and hands, because they are “important,” while cutting off the musical instruments at her feet because they are “unimportant.” (Heresy of Formlessness, rev. ed., p. 185)

Doubtless, we cannot say of the details of the sanctoral cycle that all are of equal importance; this claim would be easier to sustain of the fixed Order of Mass. Nevertheless, we love our saints — especially that somewhat “arbitrary” group that our tradition, in its slow meandering, has put right in front of us in the missal. The combination of famous and obscure saints, and the concentration of martyrs and confessors of antiquity, is itself a resounding lesson: we do not pick and choose our saints at Mass to reflect our preoccupations or favoritisms; the saints pick us, as it were, by coming to us down through centuries of devotion. It is another expression of the “scandal of the particular” in which the very essence of Christianity consists. No matter how wonderful a more recent or more local saint may be, this quality, in and of itself, does not justify the suppression of another saint who has been liturgically venerated by countless Christians for many centuries.

The solution we should favor is to let saints pile up on a given day, but decide which one gets the Mass (so to speak) and which one gets the Commemoration. The main cause of the purge in 1969 was a positive dread of having more than one set of orations per Mass, since evidently Modern Man™ is too stupid to follow more than one thread at a time. How differently we think in the era of emails, texting, and social media.

And even if, as the liturgists say, calendric simplification has happened before in the history of the Roman Rite, was it necessary to do so between the mid-1950s and the early 1970s? Who was clamoring for it? The People of God? The parochial clergy? Truth be told, it was no one but the professional liturgists, lovers of “clear and distinct” Cartesian modernity, with its glassy, steely mien, as of hygienic instruments, silver aeroplanes, and whirring time-saving appliances. The resulting empty-headedness of Catholics regarding their own heroes is, needless to say, not caused exclusively or even primarily by the loss of a rich sanctoral cycle, but surely we cannot avoid seeing a connection.

Consider the following exchange between two art historians, Martin Gayford and Philippe de Montebello, in a book called Rendez-vous with Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 2014):

MG: Some would say that putting a religious work in a museum removes its most crucial meaning. It wasn’t intended — or at least only intended — to be appreciated as a painting; it was made to be prayed before, to stand on an altar while a priest performed Mass.

PdM: Well, the meanings are in danger of disappearing anyway. The modern public by and large no longer reads the Bible, no longer knows the stories represented in the pictures. The role of museums in re-educating people in sacred stories and doctrines is very large. One could almost make the case that museums fill a gap that the churches are increasingly leaving in teaching the lives of the saints, Christ, and the Virgin, plus the stories of the Old Testament. All of the pictures and sculptures in most museums carry a label briefly telling the story, something that you do not find in church.

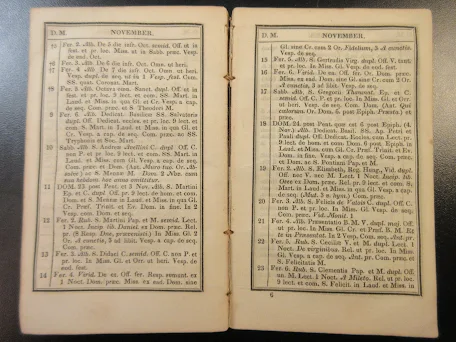

“The pictures and sculptures . . . carry a label briefly telling the story, something that you do not find in church.” Yet this is exactly what my St. Andrew’s Daily Missal (reprint of the 1948 edition) and countless other hand missals did and still do for the laity: they tell us something about every saint, and make them beloved companions of the journey.

Note that this banishment of the cultus of saints goes hand in hand with the ecumenical downplaying of all that is distinctive, the pseudo-purity of “focusing on Christ” when even He is pushed away from the closed circle, and the utter ineffectiveness of the verbal didacticism of reading so much Scripture. The people in the old days knew more about the saints and the stories of the Bible than modern believers, who are so much more “literate” and “educated.” However many causes there are of the stygian vacuity of the modern Catholic mind, we can say without hesitation that the traditional Roman liturgy emphasizes the saints vastly more than the modern liturgy does, and was capable, accordingly, of serving as a crucial pillar in a culture that saturated with the cultus of the Virgin and the saints. As Dom Guéranger writes in the general preface to The Liturgical Year:

In order that the divine type may the more easily be stamped upon us, we need examples; we want to see how our fellow-men have realized that type in themselves: and the liturgy fulfils this need for us, by offering us the practical teaching and the encouragement of our dear saints, who shine like stars in the firmament of the ecclesiastical year. By looking upon them we come to learn the way which leads to Jesus, just as Jesus is our Way which leads to the Father. But above all the saints, and brighter than them all, we have Mary, showing us, in her single person, the Mirror of Justice, in which is reflected all the sanctity possible in a pure creature.

I have to say, in passing, that the older Roman calendar reminds me much more of the Byzantine calendar, which expressly names saints in the liturgy practically every day. Of course, it works differently because their daily liturgy is not nearly as shaped and “governed” by the saint as the Roman one is — there is no concept of a “Mass of a Virgin” or a “Mass of a Confessor” in the Divine Liturgy: it has a few special antiphons sprinkled throughout for the saint, and then the rest is generic. Still, the Eastern and Western traditions bear witness to the norm throughout Christian history until the Protestant revolt: “the more saints, the merrier.” The presence of saints on the calendar augmented the glory of Christ rather than detracting from Him, as indeed the original placement of the feast of Christ the King, right before the feast of All Saints, emphasized.

Twenty-five years of working under both Roman calendars, old and new, gave me a vivid experience of the truth of Louis Bouyer’s acerbic estimation of the reform:

I prefer to say nothing, or little, about the new calendar, the handiwork of a trio of maniacs who suppressed, with no good reason, Septuagesima and the Octave of Pentecost, and who scattered three-quarters of the Saints higgledy-piggledy, all based on notions of their own devising! Because these three hotheads obstinately refused to change anything in their work and because the pope wanted to finish up quickly to avoid letting the chaos get out of hand, their project, however insane, was accepted! (The Memoirs of Louis Bouyer, trans. John Pepino [Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2015], 222–23)

To return, then, to our starting point, Saints Nabor and Felix. For many centuries the Church at prayer told her Lord that the birthday of these martyrs “never abandons us” and saw this recurring date as a promise that their intercession, too, would always be ours. Every time I encounter these “obscure” saints, I thank God for making them part of my life, for connecting me to the memory of their triumph and the power of their living intercession. Nor will this grand old calendar of saints ever cease to be followed within the Catholic Church, notwithstanding the feeble fulminations of faded flower-children.

|

| A page from my 1838 Ordo from Baltimore |