Last week, on the feast of St Apollinaris of Ravenna, we published Nicola’s photos of the basilica dedicated to him in nearby Classe. This church also houses a collection of very well-preserved early Christian sarcophagi, remains of the period (5th-8th) century when Ravenna was both an important see in northern Italy, and the seat of Byzantium’s power in the homeland of the Roman Empire. Unlike the sarcophagi seen in similar collections in places like Rome and Arles, there are no Biblical stories depicted here; the focus is rather on symbols and decorations.

A scene of the type known as the “traditio legis – the handing down of the law,” in which Christ appears in the midst of the Apostles and gives them a scroll, which represents the new law that displaces the law of Moses. This motif was

intended to answer a minority among Christians who still felt themselves very close to their Jewish roots, and insisted that all the members of the Church, whether Jewish or gentile in origin, are obliged to keep the Mosaic law. This example is unusual in that Christ is giving the scroll only to St Paul, while St Peter has his keys and cross, but does not receive the scroll. This may reflect the fact that the bishops of Ravenna under Byzantine rule were wont to assert an excessive independence from the see of St Peter. Nothing specifically identifies the other Apostles; the remaining six appear on the side panels.

In this period, there was no need for the Christians to assert the historical fact of the Lord’s Crucifixion, which was not disputed; the “hard-sell” of Christianity in the ancient world was rather the Resurrection of His body, a foolish and repellant idea to Greeks and Romans. The Cross is therefore routinely shown empty, as a way of looking forward to what happened when the Lord’s body had been taken away from it and laid in the tomb; this is, of course, an especially appropriate motif in a funerary context. The vines beneath it represent Christ’s words, “I am the vine, you are the branches”, expressing the union with Him in the Mystical Body, in virtue of which we await the resurrection of our own bodies. The birds are reminiscent of the parable of the mustard seed, Matthew 13, 31-32: “The kingdom of heaven is like to a grain of mustard seed ... which ... becometh a tree, so that the birds of the air come, and dwell in the branches thereof.”

The inscription reads “This tomb holds enclosed the body of the lord John, the most holy and thrice-blessed archbishop.” (John VI, 777-84 ca.) The term “three-blessed” reflects the rhetorical influence of the Greek liturgy, which was still widely used in many parts of Italy.

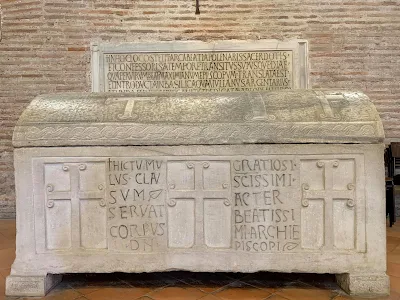

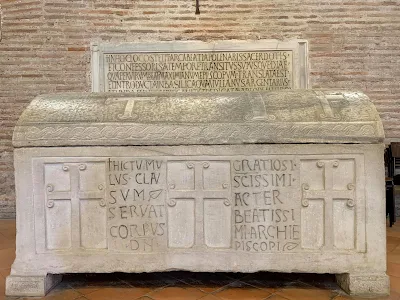

The inscription reads on the front of the sarcophagus reads “This tomb holds enclosed the body of the lord Gratiosus, the most holy and thrice-blessed archbishop”; he was the successor of John VI, ruling from roughly 785-89. The later medieval inscription behind it notes the place where the body of St Apollinaris was kept until it was translated to the new basilica named for him in Ravenna itself. The traditional account of Apollinaris’ life is not considered historically reliable; the inscription refers to him as a “confessor”, although he is now venerated as a martyr, a common happening among the Saints whose lives are not well-attested.

Sheep are a popular decorative motif on early Christian sarcophagi, in reference to Christ’s words, “I know my sheep, and my sheep know me” (John 10), and “I shall place the sheep on my right” (Matthew 25), both also highly appropriate for a funerary context. The eight-barred device in the middle is a stylized chrismon, in which the X of the well-known chi-rho symbol is combined with the bars of the cross. Several other variants appear below.

Since a peacock is mostly feather, which is dead material like our hair and nails, and since its meat is extremely salty, it takes a very long for a dead peacock to rot to the point where it doesn’t look like a peacock anymore. In ancient times, it was popularly believed that they simply do not rot at all; the Christians therefore used them as a symbol of the final resurrection which the body awaits in the sleep of death. Beneath the Cross are the four rivers of Paradise mentioned in Genesis 2.

Fragments of ancient mosaic pavement, buried under new floors added to the basilica, and rediscovered in modern times.

Some items from the basilica now kept at the National Museum in Ravenna. This fragment of the apsidal wall preserves a 6th-century “sinopia”, a shadow image made out of a particular kind of red paint, which was used as a guide for the execution of the mosaic laid over it.

A capital most likely from the pergola that originally would have separated the sanctuary from the nave; 6th century.

Two pieces of a bronze grill made in the 6th century, originally used to protect the tomb of St Apollinaris, then moved into the church’s crypt once the Saint’s relics had been translated to Ravenna.