Through most of the Middle Ages, knowledge of the Greek language was extremely limited in Western Europe. It is well-known, for example, that St Thomas Aquinas frequently cites the writings of Aristotle, but only knew them in the Latin translation of his friend William of Moerbecke. Nevertheless, from time to time we see evidence of interest in Greek in various types of liturgical texts, such as a number of medieval hymns with Greek words in them. One stanza of the Vesper hymn for Advent

Conditor alme siderum originally began with the words “Te deprecamur, Agie – we beseech Thee, holy one”, a reading which may still be found to this day in the Uses of the monks and religious orders.

At the abbey of St Denys outside Paris, a major center of learning, a custom had developed by the second half of the ninth century of singing parts of the ordinary of the Mass in Greek, at least on some occasions. A sacramentary of that period now at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, but originally used at an abbey associated with that of St Denys, has the

Gloria, Creed,

Sanctus and

Agnus Dei all in Greek. Much later, in the 16th century, St Denys itself instituted the custom of singing the entire Mass on the Octave day of their Patron Saint in that language, a tradition which continued until the French Revolution. This was not the Byzantine Divine Liturgy, but the Mass of the Roman Rite translated into Greek. By that period, St Denys was believed to be the same person as “Dionysios the Areopagite”, who is mentioned at the end of Acts 17 as one of the persons converted by St Paul’s discourse to the Athenians. (The name “Denys” derives from “Dionysios.”) The legend continued that he was the first bishop of Athens, who had then gone to Rome and been sent by Pope St Clement I to evangelize Paris, of which city he was also the first bishop, and where he was martyred.

|

| The martyrdom of St Denys, and his companions Rusticus and Eleutherius, depicted in the tympanum of the north portal of the Abbey of St Denys. (12 century - image by Myrabella from Wikimedia Commons.) Denys is shown holding his own decapitated head, which his legendary medieval life says he picked up and walked with from Montmartre (“the mount of the martyrs”) to the place which would later become the site of the Abbey. |

In the year 827, the Byzantine Emperor Michael II sent to the Western Emperor Louis the Pious a copy of the collection of Greek theological treatises and letters ascribed to the Areopagite, which are actually works of the late 5th or early 6th century. These happened to arrive in Paris and be taken to the Abbey of Saint-Denis on the very eve of his feast day. The abbot Hilduin translated them into Latin, a translation which, although not very accurate, and later supplanted by better ones, made “Dionysius the Areopagite” one of the most important influences on the theological writers of the Middle Ages. (He is actually cited more often in St Thomas’

Summa Theologica than Aristotle.) Hilduin also wrote a biography of the Saint, the first to identify all three personages as the same man; this imposture, which contradicts much of what earlier writers say about him, has unfortunately become an all-too-useful stick in the hands of

hagiographical skeptics for beating on the legends of other Saints. (It also contradicts the tradition of the Byzantine Rite, which honors him on October 3rd as the first bishop of Athens, but knows nothing of his association with Paris.)

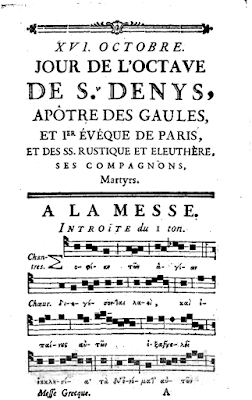

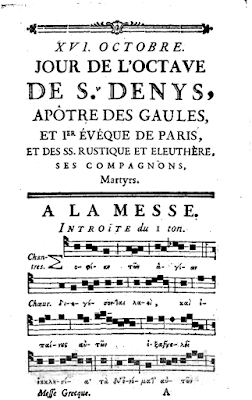

The Greek Mass was certainly instituted to honor the Abbey’s patron not only as an important writer of theology in Greek, but also the first bishop of the most important cultural center of the ancient Greek world. The complete text of the Mass was published at Paris in 1777; it can be found on Google Books by searching for “Messe grecque en l’honneur de Saint Denys”, but due to who-knows-what mysteries of copyright law, cannot be downloaded in every country. Here are a few pages of it, in honor of his feast day.

|

| The Gregorian Introit “Sapientiam Sanctorum” from the Common of Several Martyrs (continues on following page). The Greek font used here is different from that used in modern printed editions of classical texts, since it is based on medieval Byzantine handwritten scripts. |

|

| The Collect and the beginning of the Epistle, Acts 17, 22-34 |

|

| The Gregorian Offertory “Exsultabunt Sancti” |

|

| The Roman Common Preface above, and the neo-Gallican proper preface below. |