The entire floor of the nave is taken up with beautiful tomb slabs of inlaid marble, predominantly of the bishops and cathedral canons; an example is shown further down. (The entire floor of the co-cathedral of St John the Baptist in Valletta is similarly decorated, but the tombs are those of various Knights of Malta.)

Saturday, June 30, 2018

The Cathedral of St Paul in Mdina, Malta

Gregory DiPippoThe entire floor of the nave is taken up with beautiful tomb slabs of inlaid marble, predominantly of the bishops and cathedral canons; an example is shown further down. (The entire floor of the co-cathedral of St John the Baptist in Valletta is similarly decorated, but the tombs are those of various Knights of Malta.)

Bibliography of Dominican Liturgical Books

Fr. Augustine Thompson, O.P.Greetings to our readers,

I have been working on a bibliography of the printed editions of Dominican liturgical books for some time and have now made it available online. It is very long and would overburden NLM’s daily presentation of posts, so I have made it available on Dominican Liturgy, my own blog.

If you notice anything missing or any errors, do let me know in the comment box over at Dominican Liturgy, rather than here. I hope that some of our readers find this useful.

Artworks Restored in Italy (Part 1)

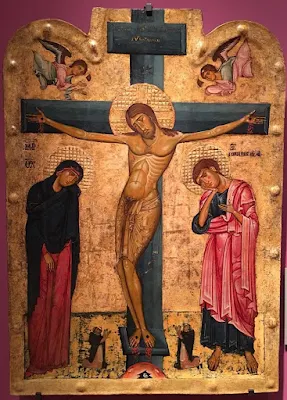

Gregory DiPippoCrucifix by the Master of St Peter in Villore, 1175-1200; from the diocesen museum of Pienza in Tuscany.

Dominican Rite Sung Masses in Malta

Fr. Augustine Thompson, O.P. I am pleased to announce that during July, Fr. Alan Joseph Adami, O.P. will celebrate sung Masses according to the traditional Dominican Rite at St Paul’s Chapel, Valley Road, Birkirkara, Malta. These Masses will occur at 7:00 p.m., on July 1 and 15; August 19; and September 2, 9, and 16.

I am pleased to announce that during July, Fr. Alan Joseph Adami, O.P. will celebrate sung Masses according to the traditional Dominican Rite at St Paul’s Chapel, Valley Road, Birkirkara, Malta. These Masses will occur at 7:00 p.m., on July 1 and 15; August 19; and September 2, 9, and 16.This announcement is decorated with images Fr. Adami’s First Mass (also in the Dominican Rite) this last April at the Maltese Latin Chaplaincy.

Friday, June 29, 2018

The Feast of Ss Peter and Paul 2018

Gregory DiPippo |

| The Crucifixion of St Peter, depicted in the Papal Chapel known as the Sancta Sanctorum at the Lateran Basilica in Rome, ca. 1280. |

|

| The Beheading of St Paul, also from the Sancta Sanctorum. |

Photopost: CMAA Colloquium Solemn Requiem Mass in the Usus Antiquior

Jennifer Donelson-NowickaPhotopost: Ordinary Form Mass in Spanish at Colloquium Day 2

Jennifer Donelson-NowickaThursday, June 28, 2018

Liturgical Objects Restored in Italy

Gregory DiPippoA velvet chasuble of the mid-15th century, reworked in the mid-18th, decorated in the middle with silk embroidered with metalic threads.

Tradition is for the Young (Part 14)

Gregory DiPippo“One person asked whether there would be more parishes celebrating Mass in the extraordinary form, to which the Bishop replied, ‘Tell me, what is the attraction to the Latin Mass? It’s interesting to me that the push for this is coming not from the old, but from the young.’

‘I think what drew me to the Latin Mass was the beauty and the mystery,’ said one responder. ‘It’s probably the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.’ Bishop O’Connell agreed. ‘There’s something about the mystery of the Mass, in a time when many things are so mundane ... so for those for whom Latin is spiritual nourishment, I encourage it.’ Another attendee, Francis, called it ‘a beautiful, living history – it made me want to grow deeper in faith.’ ”

Wednesday, June 27, 2018

1962 Vocational Film, Starring Jack Nicholson

Gregory DiPippoIn December of 2016, we shared a film made by the Paulist Fathers in the mid-1960s to promote vocations, in which the actor Brian Keith, who later played Uncle Bill on Family Affair, had a small part.

Prudence, Pizza, and Role Fatigue in the Liturgy

Joel MorehouseIf faith put in practice is to persevere, it must also be sustainable and dynamic. Quite simply, the Eucharist is the source and summit of all Catholic life; therefore, if someone burns out with the liturgy, he or she will not persevere in faith. This is where questions of prudence and role fatigue come into play. Let’s begin with two examples:

I recall an invitation to sing in a Gregorian chant schola that rehearsed Sunday mornings at 5:30 am and sung for a 7:00 am Mass. It was a good group, so naturally I was interested; however, as much as our readers know my deep love of Gregorian chant and traditional liturgy, I confess that my first utterances upon hearing the alarm at 4:30 that morning were not in praise of the benevolent Creator. The time simply didn’t work with my other responsibilities, and I quit after the first season. Three of the men in that group are now faithful Benedictine monks, and I am a faithful lay Catholic, married and serving full-time in a parish. If practicing my Catholic faith required me to wake up every Sunday at 4:30am, I probably would have quit. Thank God there were options that were more prudent for me at the time.

Prudence and role fatigue don’t simply apply to time commitments but also to ideological tenacity, one’s participation in society at large, the battles one fights, one’s emotions, and even family and intergenerational dynamics. I call to mind someone who, in younger years, had been a public champion for traditional liturgy with all of the trappings. All of a sudden one day, she quit Catholicism entirely, because she had grown tired of fighting. She could only conceive of Catholicism as a sort of sacralized politics, an ever-present revolution where every minute detail was a sign of a larger battle of good and evil. She had fatigued in a role, a closed cycle of anxiety, that admitted no change, development, or relief. The last I heard, she was delivering pizzas.

In these two examples, one might argue that God’s grace was not lacking. Grace gives one supernatural ability to accomplish what is naturally impossible. No Catholic marriage lasts, nor does any priest remain faithful to his vocation, without it. Every good action is inspired, sustained, and brought to perfection through the working of grace. I get it; but no person receives exactly the same gifts and graces. I have prayed for the grace of being a cheerful early riser, and all I have been given is black coffee and an alarm clock.

Nevertheless, prudence and subsidiarity are key principles for perseverance and sustainability. Prudence is key insofar as a community must apply the liturgical norms obediently, to the letter of the law, but also in a manner that takes into account the stakeholders in the community. Early risers, golfers, monks, and farmers may appreciate a quiet 6:00 am Mass; urban families may prefer a sung 11:00 am; college students may appreciate a candlelit 10 pm. Within the norms, therefore, a parish needs to cast a broad net. In this sense -- and obediently keeping the applicable norms -- the variation of practice is a sign of healthy subsidiarity. Subsidiarity is key insofar as it allows one local parish to differ from another; similarly it allows the pastor to vary the culture within the parish from a short low Mass with no music, to a two-hour High Mass with incense, soaring music, and innumerable servers. A good shepherd knows his sheep, and accordingly a good pastor, in his role as liturgist, knows what sustains the people he serves, and what they in turn can support in the various para-liturgical ministries such as choirs, altar servers, etc. It is often a varied diet.

Others also share in the pastor’s responsibility to sustain the faith of the people of the parish. Writing as music director in a parish of 4,500 families, with extraordinarily strong Mass attendance and a regular diet of orchestral Masses, Gregorian chant, polyphony, hymns, and organ repertoire, my responsibility is to engage as many people as possible in our various choirs, scholas, and other ensembles; and through them, to support the sung prayer of all in the parish. My success or failure depends on my ability to make participation in my choirs sustainable, fun, worthwhile, and engaging for each member, while at the same time reaching deeply, together, into the authentic sacred treasury of our Catholic tradition. All is done so that God would receive fitting praise, as beautiful and noble as our community is able to offer. It is possible to have the right goals, and still miss the mark-- whether it's the right music at the wrong time, or too much unfamiliar repertoire at once, or not enough fun and recreation. It takes time and wisdom to find the balance.

I respectfully issue a challenge, to anyone who might join me, that the work of restoring the liturgy isn’t so much about argument, as about ongoing education; it isn’t so much a sprint, as it is daily persistence toward a worthy goal. The old house is not restored in one effort, nor the fractured neighborhood reunited in a single week; both are restored by a commitment to live and to remain amid the challenges, with joy and gentle strength. Virtue is the wisdom to fix the roof before the rains, the humility to ask for help when “you’re in over your head”, the patience to teach one’s children to keep the garden, the generosity to help a neighbor with a project… and lastly it is respect for the tools, for the work itself, and for one’s companions.

Opening Mass of the CMAA Colloquium

Charles ColeTuesday, June 26, 2018

The Feast of Ss John and Paul, Martyrs

Gregory DiPippoThe Passion of the Holy Martyrs Saints John and Paul, as recounted in the pre-Tridentine Breviary according to the Use of the Roman Curia.

|

| The exterior of the church of Ss John and Paul, which was completely rebuilt in the 12th century. |

|

A later and apocryphal tradition says that Julian the Apostate was killed by a Christian soldier in his army named Mercurius, (who is honored in the East as a Saint), as depicted here in a Coptic icon. (image from wikipedia.) The true historical date of Julian’s death is the same as the feast of Ss John and Paul, June 26th.

|

R. This is the true brotherhood, which could never be injured in the struggle; who by shedding their blood, followed the Lord. * Disdaining the palace of the king, they came to the heavenly kingdom. V. Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell in unity. Disdaining. Glory be to the Father. Disdaining.

In the Breviary of St Pius V and its predecessors, this responsory is said on the feasts of Several Martyrs who are also brothers. The devotion to John and Paul is one of the oldest in the city of Rome, and the responsory was almost certainly originally written for their feast day.

A New Book On Discerning Your Personal Vocation and How to Make It Happen

David ClaytonFurthermore, I thought that those who are in the Church and are happy, so that they do need feel any particular need to go through such a process, might nevertheless be interested in David’s method of evangelization so that they can use it themselves. The main weapon, so to speak, that David had was that he was so obviously at peace, and he also knew how to transmit this to others. I describe in some detail, as best as I can remember so many years later, the conversations we had and how he went about convincing me that he had something he could pass it on to me, without my ever feeling I was being manipulated or pushed into something I didn’t want to do.

Finally, the route to happiness that this program gave me was through the discernment of my personal vocation. My belief is that many people who are unhappy in life, whether Catholic or not, are unhappy because they are not doing what they are meant to do. This process, I believe, can offer a new direction that may bring the happiness you are looking for. When I met David, I was so unhappy that I was about to look for a therapist or psychiatrist who could offer counsel - or a prescription - that could change the way I felt. David suggested to me that I might like to wait and see how I felt after the process, because he thought it might solve my depression. I am glad that I followed his advice.

My experience is that this process was able to take me from where I was to where I ought to be. The degree to which this will re-order you life depends, of course, on how far you are from the path that God intends for you. In my case, this was a profound dislocation that didn’t just change the direction of the path I was on, it helicoptered me onto a whole new path. And again, what is remarkable about this, is that once I discovered the degree where it was taking me, I was more than happy to go along with it.

I decided to write it now, so many years after David died, in part because I noticed that the blog posts I referred have had as positive response as any that I have written. Also, I have now had experience of taking several dozen people through this process myself and have seen it work for them too. All of them were given either a new or deeper faith in God, and several have even converted or returned to the Church. This has given me the confidence to believe that I have sufficient experience and understanding of the process to put it writing for, one hopes, the benefit of others.

The Vision for You, How to Discover the Life You Were Made For can be ordered online here.

Posted Tuesday, June 26, 2018

Labels: Book Review, David Clayton, London Oratory, New Evangelization, personal vocation

Monday, June 25, 2018

A Brief Dialogue on Liturgical Development and Corruption

Peter KwasniewskiOliver: I've often hear you say, Charlie, that the Novus Ordo represents a huge rupture with the preceding liturgical tradition. But you never comment about other changes in the history of liturgy, like the development of the whispered low Mass, that also break with preceding tradition — I guess because traditionalists are okay with these things. So what’s the difference? When is a new direction not truly a rupture? Or is it a “development” if you happen to agree with it, and a “rupture” if you happen to dislike it?

Charles: Great question. I would say that developments come in two basic “flavors”: those that flow forth in harmony with something profoundly within the liturgy, like a flower from a tree, and those that are imposed from without in a mechanistic way, like a prosthetic limb.

Oliver: Could you illustrate your distinction in reference to the low Mass example?

Charles: The liturgy is certainly meant to be sung in its solemn form — you, of all people, know I’ve defended that many times. However, the mystery of the Mass also allows for and invites the priest to an intense mysticism of intercession, oblation, and communion. Thus, it is easy to see how, especially in monastic settings with an abundance of priests, the private daily Mass emerged in contradistinction to the conventual or parochial Mass. This need not be seen as a problem, unless it becomes the norm for communal Mass and edges out the sung liturgy.

Oliver: But how would you defend the proposition that this change was incidental and not substantive?

Charles: One might say that the same Mass exists at different levels of execution, like the difference between a Shakespeare play read quietly to oneself, the same play read aloud by a group of friends, and the play fully acted out in costume on the stage with props and so forth. It is the same play, but realized more or less fully according to its essence as a play. Any of those actualizations of the play are based on one and the same play. Think how different it would be if, instead of this, you had a modernized redaction of Shakespeare that purged Catholic references so as not to offend Protestants, changed the vocabulary to contemporary English, and changed the gender of the starring roles! In the latter case, even if the play was given the same title, it would no longer be the same reality — no matter how well you acted it out on stage.

Oliver: I see what you’re getting at. But here’s something that’s bothered me. How long does it take until something can be considered part of ecclesiastical tradition? If a parish has communion in the hand for 40 years, does this then become part of tradition? Imagine if — God forbid! — altar girls are the norm for the next hundred years. In the year 2118, can one look back and say “this is not and never has been ecclesiastical tradition,” or would one say “this is a tradition, but it’s bad and we should change it”?

Charles: Let’s take up the question of communion first. When the Latin Church shifted in the Middle Ages to communion under the species of bread alone, given on the tongue to faithful who are kneeling, it was for good reasons: it fosters a spirit of humility and adoration, and, on a practical level, is easier and safer. It is, in other words, completely in accord with the letter and spirit of the liturgical action, something that emerges from a deeper grasp of the mystery of the Holy Eucharist. Therefore, there could never be a compelling reason to undo this development, unless we wanted less safety, less humility, and less adoration. But that could only come from the devil.

In fact, Paul VI himself recognized that communion on the tongue was superior and reasserted it, although he then allowed the abuse of communion in the hand to sweep over the Church because he was an indecisive and confused shepherd — even his best decisions still have something of Hamlet mixed in with them, as when he called a commission to look into contraception, which raised false hopes among the progressives. But I digress…

Oliver: So you don’t buy the argument that it was good to restore communion in the hand because “it’s what used to be done in ancient times”?

|

| The right way |

Oliver: Would this apply to the Novus Ordo as well, since it was universally put in place of the old rite of Mass?

Charles: Of course not. First, thanks to the protection of the Holy Spirit, Paul VI, who wanted to abolish the old liturgy, never successfully abrogated it, as Pope Benedict XVI later acknowledged. So the old liturgy has always remained legitimate (and, indeed, it could never be otherwise). Moreover, while the Tridentine liturgical books were eventually received universally, the Novus Ordo was resisted from the beginning by an intrepid number of clergy and laity, and this refusal to accept the rupture has not faded away but has actually grown over the decades. In this way it is simply a fact that the Novus Ordo, while unfortunately the predominant rite, cannot be said to have supplanted and replaced the old rite, whereas communion on the tongue to kneeling faithful totally replaced any other manner of reception in the Middle Ages. Thus one cannot, in principle or in practice, make the argument that the more recent rite is superior to the more ancient rite. But one would have to say quite a bit more on this matter, and maybe we are drifting from the main point...

Oliver: Let me ask a general question. Why don’t you think there should be continual change in the liturgy — you know, different things for different ages and peoples?

Charles: I recognize that there can and will be small changes, like the addition of new feasts or saints to the calendar, or new prefaces, but not large-scale changes. Church history shows that development starts out at a more rapid pace and slows down increasingly as the liturgy reaches perfection. In a way, it is like molten lava that erupts from a fissure and gradually cools to become solid. In the same way, the liturgy gushed forth from the heart of Jesus on the Cross, and solidified over the centuries as holy men and women continued to pray it, showing great reverence to what they inherited from their predecessors.

Oliver: The Byzantine Divine Liturgy, for instance, has changed very little over the last several centuries, and the great majority of Eastern Christians see no need to change it, since it accomplishes so well what it exists for.

Charles: Exactly. The traditional Roman liturgy grew to its mature grandeur more slowly than did the Byzantine, but the same progressive solidification and the same conservative instinct can be seen in it. The Roman Canon was complete by the start of the seventh century; then most of the remaining ceremonies by the early Middle Ages; and finally the prayers at the foot of the altar and the Last Gospel in the late Middle Ages. At this point it no longer needed to evolve and could remain solid and stable for almost 500 years (from 1570 to 1962). Those who use it today see no need to “develop” it further; on the contrary, they unanimously wish to keep the Mass in its fullness, prior to the corruptions introduced by Pius XII after 1948.

Oliver: I know that some people compare the process you are describing to the way a human being develops. Do you think that analogy holds? It seems like one would run into the problem of aging and senility…

Charles: Rightly understood, this analogy works. A child changes tremendously on the way to adulthood, but the pace of change becomes less as time goes on. Everyone knows that one year of time means something very different in the first 10 years of life, the second 10 years, and the remaining decades. Time, for organic things, is not simple and undifferentiated. And if we were not fallen beings, we might remain adults at approximately age 33 for our entire lives. The liturgy grows to maturity and then remains at maturity, without fail, until the second coming of Christ. Hence, a strange custom that arises in the 20th or 21st century cannot lay claim to being a natural development but is more like a cancerous tumor in a body. It is like an infantilization, a rejection of maturity.

Oliver: But what do you make of my altar girl example? What if we had them for over a century?

|

| All made up and nowhere to go |

Oliver: That makes a lot of sense.

Charles: And by the way, you have to resist a lie that has gained a great deal of ground, namely that matters of liturgy are on a different plane than matters of doctrine. Someone might say, disputes about the divinity of Christ are one thing; disagreements about the liturgical discipline of altar servers is quite another. Don't lump together Arius and Bugnini, or Honorius and Paul VI. But in reality, every liturgical question stems from and resolves to a doctrinal question. Nothing we do in our worship is doctrinally neutral or irrelevant or inconsequential.

Oliver: That certainly seems true, if you just look at the shift in the beliefs of ordinary Catholics from preconciliar to postconciliar times. The next logical question, I guess, would be this: How do we know what stage of development the Church is in right now? I could imagine the faithful in the 15th century saying: “A strange custom that arises in the 15th century cannot lay claim to being a natural development but is more like a tumor.” And are not some innovations, such as the centralized tabernacle on the altar, considered to be a non-tumorous change even though it did not come about until rather late?

Charles: Perhaps the solution to this conundrum is to look at why people make the changes they make. In the 15th century — or, for that matter, any century — liturgy is developed in the direction of expansion. People add processions, litanies, extra prayers, repetitions. They do this out of devotion. It is rare that such things are pruned, though it does happen from time to time. However, what is absolutely unprecedented is for very many things to be cut back simultaneously and as a result of utilitarian, rationalist, and activist presuppositions, as occurred in the 1960s. So I think one can see a crucial difference between earlier phases of development, which involve positive growth, and the contrary motion of corruption, which is opposed to that growth and in fact tends to hate it and attack it iconoclastically — always a sign of the Evil One. When altars got bigger and grander, it was a development. When altars were jackhammered and dumped, it was a rupture.

Oliver: How is one to know that some change ought to be made?

Charles: Anything that belongs to the practical order will involve the exercise of the virtue of prudence: we are making a judgment about what it is prudent to change. But always with a tremendous, even fearful respect for all that has been received in tradition! That is why the Second Vatican Council, in one of its more sober statements, said: “There must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them; and care must be taken that any new forms adopted should in some way grow organically from forms already existing” (Sacrosanctum Concilium 23). The Council Fathers were mostly pastors of souls, and they knew that too much change at any time, for any reason, is a bad thing, as St. Thomas explains when discussing why even laws that are imperfect should not necessarily be replaced with better laws, because it weakens the confidence people have in habitually following laws in general.

Oliver: Of course, bringing back the old Latin liturgy is a change of custom for most Catholics, so it, too, could weaken their sense of ecclesial stability or trust. What do you say to that?

Charles: The only justification that can be given for such a big change is that the good of recovering liturgical tradition overwhelmingly outweighs the evil of disturbing people’s habits. Besides, churchmen since the Second Vatican Council have given us so many reasons to distrust their decisions that it’s rather silly at this point to suggest that we can be destabilized more than we have already been by all the doctrinal confusion, moral laxity, and liturgical chaos of the past five decades. The return of tradition means a return of dogma, holiness, and right worship — all stabilizing factors. It’s like going from anarchy to government, or from a starvation diet to a royal banquet. Only a cruel person would say: “The poor are so accustomed to malnutrition that we should just let them stay at that level, even though we are capable of providing them with abundant nutrition.”

Oliver: Your arguments make me wonder about the use and abuse of Church authority. Would you say there was a similar (although not nearly as bad) problem when the Council of Trent suppressed rites? It seems to me that after Trent the idea of what the liturgy is in relation to the Vatican undergoes a shift.

Charles: Yes, Trent, or perhaps I should say St. Pius V, does introduce a new dynamic. He did not abolish any rite older than 200 years, but the way the new missal was imposed showed a tendency to overreach.

Oliver: One can sympathize; it was a centralized response to the centrifugal force of Protestant experimentation and diversity.

Charles: For sure. I don’t deny that. But in 1570, for the first time in history, a pope took upon himself the role of officially promulgating a missal for the Latin rite Church. It’s quite striking, isn’t it, to think that Catholicism endured for 1,500 years with a rich liturgical tradition that had never been administered or validated by the Vatican?

Oliver: The only thing more striking, one could say, is that Paul VI was audacious enough to introduce a new missal, which Pius V would never have done, or even conceived of doing. His 1570 missal was, for all intents and purposes, the same as papal curial missals had been for centuries before.

Charles: You are provoking me, aren’t you, to take up the question of whether or not Paul VI’s manufactured liturgy can seriously be called the Roman Rite, and whether this talk of “two forms” can really be defended. That’s a longer conversation, for another day. But this much should give us pause: never in the history of the Catholic Church had there been a new missal, until 1969.

Oliver: Whatever the answer may be, it won’t change where I’ll be heading for church on Sunday. See you at the High Mass for the Sixth Sunday after Pentecost!

Charles: You bet.

Sunday, June 24, 2018

The Dawn Mass of St John the Baptist

Gregory DiPippoThis custom of the two Masses gradually died out, and was observed only in a few places at the time of the Tridentine liturgical reform; the Mass which survived, and is included in the Missal of St Pius V, is the second one, and the older of the two. Here is the full text of the dawn Mass; medieval commentators such as William Durandus noted that the day Mass was the more solemn, since it has more proper texts, while most of the Gregorian chants for the dawn Mass are also used on the feasts of other Saints.

Introit The just man shall flourish like the palm tree: he shall grow up like the cedar of Libanus, planted in the house of the Lord, in the courts of the house of our God. ℣. It is good to give praise to the Lord, and to sing to Thy name, O most High. Glory be. The just man...

Collecta Concede, quaesumus, omnipotens Deus: ut qui beati Joannis Baptistae solemnia colimus, ejus apud te intercessione muniamur. Per.

Collect Grant, we ask, almighty God, that we who keep the solemnity of blessed John the Baptist, may be defended by his intercession. Through Our Lord...

The Epistle for this Mass varies from one Use to another; in the Parisian version shown above, it is taken from Isaiah 48 (verses 17-19), the chapter preceding that from which the Epistle of the day Mass is taken.

Thus saith the Lord thy redeemer, the Holy One of Israel: I am the Lord thy God that teach thee profitable things, that govern thee in the way that thou walkest. O that thou hadst hearkened to my commandments: thy peace had been as a river, and thy justice as the waves of the sea, and thy seed had been as the sand, and the offspring of thy womb like the gravel thereof: his name should not have perished, nor have been destroyed from before my face.

The Gradual repeats the text of the Introit, with the second verse of the same Psalm.

Graduale Justus ut palma florébit: sicut cedrus Líbani multiplicábitur: plantátus in domo Dómini, in atriis domus Dei nostri. ℣. Ad annuntiandum mane misericordiam tuam, et veritatem tuam per noctem.

Gradual The just man shall flourish like the palm tree: he shall grow up like the cedar of Libanus, planted in the house of the Lord, in the courts of the house of our God. V. To show forth thy mercy in the morning, and thy truth in the night.

In some places, the Alleluia repeats the same words from Psalm 91 a third time, but in others, it was taken from the Savior’s own testimony to the greatness of John, from Matthew 11, 11.

|

The Preaching of John the Baptist, by Domenico Ghirlandaio, in the Tornabuoni Chapel of Santa Maria Novella, the Dominican parish in Florence, 1485-1490.

|

At that time: Zachary said to the angel: Whereby shall I know this? for I am an old man, and my wife is advanced in years. And the angel answering, said to him: I am Gabriel, who stand before God: and am sent to speak to thee, and to bring thee these good tidings. And behold, thou shalt be dumb, and shalt not be able to speak until the day wherein these things shall come to pass, because thou hast not believed my words, which shall be fulfilled in their time. And the people were waiting for Zachary; and they wondered that he tarried so long in the temple. And when he came out, he could not speak to them: and they understood that he had seen a vision in the temple. And he made signs to them, and remained dumb. And it came to pass, after the days of his office were accomplished, he departed to his own house. And after those days, Elizabeth his wife conceived, and hid herself five months, saying: Thus hath the Lord dealt with me in the days wherein he hath had regard to take away my reproach among men.

|

| The Annunciation to Zachariah, by Giovanni di Paolo (ca. 1455-60; public domain image from the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.) |

Offertory In thy strength, O Lord, the just man shall rejoice, and in thy salvation he shall exsult exceedingly; thou hast given him his soul’s desire.

Secreta Munera, Domine, oblata sanctifica; et intercedente beato Joanne Baptista, nos per haec a peccatorum nostrorum maculis emunda. Per...

Secret O Lord, sanctify the gifts offered; and by the intercession of blessed John the Baptist, through them cleanse us from the stains of our sins. Through Our Lord...

The Communion antiphon is one commonly used for the feasts of Confessors.

Communio Posuísti, Dómine, super caput ejus corónam de lápide pretióso.

Communion Thou hast set, o Lord, upon his head a crown of precious stones.

Postcommunio Praesta, quaesumus, omnipotens Deus: ut qui caelestia alimenta percepimus, intercedente beato Joanne baptista, per haec contra omnia adversa muniamur. Per...

Postcommunio Grant, we ask, almighty God, that we who have received the food of heaven, by the intercession of blessed John the Baptist, may through it be defended from all adversities. Through our Lord...

Friday, June 22, 2018

Photos of Ambrosian Corpus Christi

Gregory DiPippoA decorative collar called a cappino is attached to the top of a chasuble, dalmatic or tunicle at the back. During the incensations, the chasuble is held up higher than is typical in the Roman Rite, parallel to the floor.

The thurible has no top, and is swung in circles in a manner than keeps its contents from flying out. (This takes some practice.)