Painting and Viewing the Nude in Christian Art

I recently read a short but excellent discussion of the place of nudity in Christian art written by Deacon Lawrence Klimecki. For Deacon Lawrence, the question turns on the judgment as to whether or not the nudity distracts from the Christian purpose of the art. This will depend on the response of the people who are meant to see it and the skill of the artist in representing nudity in an ordered way. I encourage you to read it.

Here is a different, but complementary argument that I make that supports his assertion that it is appropriate, but only in certain circumstances. What follows is a summary of a longer article published some time ago in a Festschrift for my friend Stratford Caldecott.

This caused quite a stir at the time. Here was a respected Pope (now a Saint) who was putting his intellectual weight behind the artistic tradition of painting the nude... and not only excusing it, but promoting it! Many cultured and arty Catholics in the chattering classes heaved a sigh of relief. Now they could point to the words of the Pope and claim that they were right at the cutting edge of culture and simultaneously in the mainstream of the Church! Now they were as free to air their views over coffee after Mass as they were with their secular friends at dinner parties, for the Pope, no less, had become an apologist for the Sixties! After all, he was telling the Philistines who were uncomfortable with nudity that they didn’t really understand Catholic culture. Many artists didn’t miss the point either. The Pope’s challenge to them inaugurated the creation of a wave of contorted Theology-of-the-Body nudes that, the artists told us, communicated human sexuality “as a gift” through the exaggerated gestures of intertwining limbs and torsos.

Initially, I accepted this view too, to a degree. Then I actually read the Theology of the Body and John Paul II’s address on the re-opening of the Sistine Chapel.

Several years ago, when I moved to the US from the UK and started teaching at a Catholic college, I knew that I would have to deal with devout Catholic parents who might be hesitant about allowing their sons and daughters to draw nudes in figure-drawing classes. I imagined that they would have been even more nervous about the idea of some of them posing for the classes.

In order to have some good Catholic arguments to persuade them of the appropriateness of this, I set about looking at the tradition of the nude in Catholic art, while also reading the Holy Father’s words on the subjects.

I was surprised by what I came up with. Rather than finding evidence to bolster my view, I found the reverse. I had to abandon certain assumptions that I had held until that point and adopt some new ones:

Several years ago, when I moved to the US from the UK and started teaching at a Catholic college, I knew that I would have to deal with devout Catholic parents who might be hesitant about allowing their sons and daughters to draw nudes in figure-drawing classes. I imagined that they would have been even more nervous about the idea of some of them posing for the classes.

In order to have some good Catholic arguments to persuade them of the appropriateness of this, I set about looking at the tradition of the nude in Catholic art, while also reading the Holy Father’s words on the subjects.

I was surprised by what I came up with. Rather than finding evidence to bolster my view, I found the reverse. I had to abandon certain assumptions that I had held until that point and adopt some new ones:

- It is not necessary to study the nude to draw or paint the human person well, even in naturalistic styles.

- The Christian tradition is very cautious about nudity in art, and for the most part, avoids it. The nude appears consistently in the tradition only a very limited way, and in connection with certain subjects (e.g. Genesis and the account of the Fall), where it is crucial to understanding the passages. It has to be in accord with compositional and stylistic considerations that maintain the dignity of the person portrayed.

- The artist has to take into account the sensibilities of the time, which can vary. The artist must always avoid lasciviousness, but what that means precisely will be different at different times.

- John Paul II himself was, consistent with tradition, extremely cautious about the portrayal of the nude. He most certainly was not promoting in any way of the liberal attitudes of the 20th century. He advocated that naturalistic styles of art, as distinct from highly idealized styles, should not be used to portray the nude.

In fact, he said that the human person should only be portrayed nude when we see the body shining with the “light that comes from God.” This narrows the scope considerably. It is a reference to what is called in the context of traditional iconography the “uncreated light” of sanctity. He is proposing that only highly idealized representations of the human form are appropriate for the nude. While this doesn’t rule out new interpretations consistent with the principle, historically, it points strongly either to the highly stylized iconographic tradition, as seen here,

|

| An icon of the Baptism in the Jordan. |

|

| The Temptation, from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry |

In common with many other Christian commentators, John Paul II also admired the nude as portrayed in ancient Greek sculpture.

It is the correspondence to this idealized form, and not its naturalism, that causes him to appreciate the work of Michelangelo so highly, especially his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel.

Rather than blandly stating that the human body is beautiful, it is always appropriate to show it nude, we must recognize that man after Fall, which is who we are, does not shine with light in the same way, and is prone to look in an impure way at the other. With this in mind, the way to restore man after the Fall, which John Paul II called Historical Man (i.e. all of us now) to the dignity of Original Man (man before the Fall), whether in art or in reality, is the same: put some clothes on, for heaven’s sake!

Clothes on fallen man don’t hide the beauty of the body; they complete it in a dignified way. That is why, incidentally, it is traditional to have masculine and feminine clothes - so that human sexuality can be revealed in an ordered way. To put it bluntly: before the Fall, man was clothed in glory; after the Fall, man retains his dignity by being clothed!

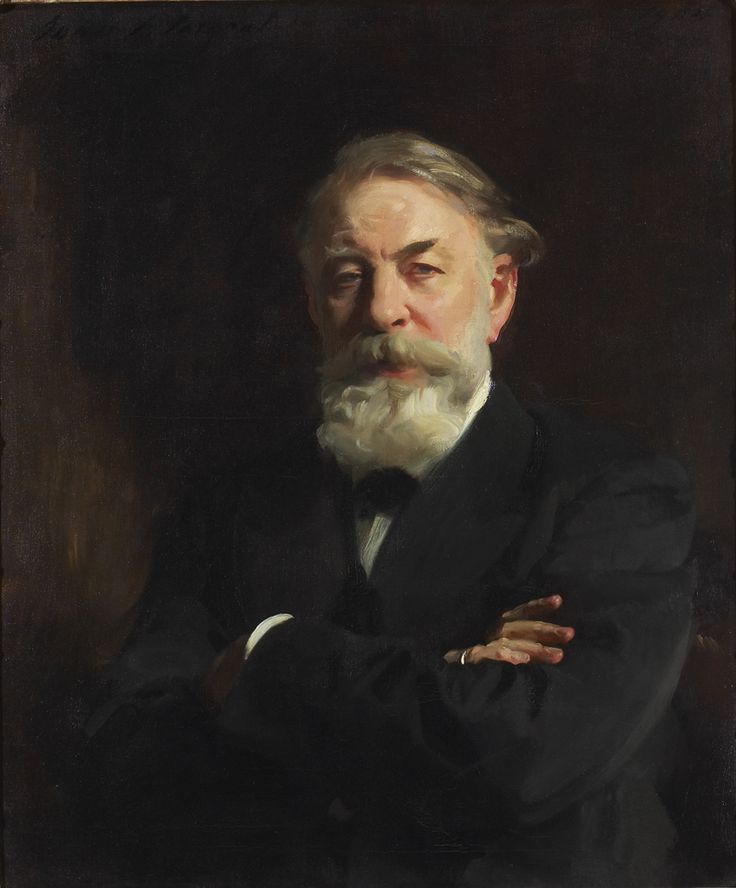

|

| Portrait by John Singer Sargent |

We must also consider not only the effect of the image on the observer, but also how the process of creating the image affects both the model and artist. It is often stated that the etiquette of the studio, by which the model disrobes behind a screen, and no one other than head of the studio speaks to him or her when nude, protects the dignity of the model.

In fact, even if we accept that such etiquette does remove the general indignity of baring oneself in front of others, and the erotic charge that might otherwise be present when the model is attractive, it does so by objectifying the person; that is, it creates a situation in which we no longer view the model as a person, but as shaped flesh. We need to be aware, therefore, that this approach might still be participating, albeit in a different way, in the problem of the modern understanding of the human person that the Pope is trying to remedy. Perhaps in removing one difficulty, we are replacing it with another.

There are two other reasons that are often adduced in favor of the nude which I feel are wrong. The first is that it is a longstanding part of the Christian tradition of art. As far as I can ascertain, this is not quite the case. Christianity drastically reduced the degree of nudity in art, compared with the pagan art that preceded it. Only with the Renaissance did we start to see nudity appearing in art beyond certain very carefully designated situations, like Adam and Eve and the Baptism in the Jordan, as seen above.

Even then, as we have already mentioned, the style is important. Only those artistic styles developed to portray the person bathed in the uncreated light of God are appropriate for nudity, says John Paul II, for, “If it is removed from this dimension, it becomes in some way an object which depreciates very easily, since only before the eyes of God can the human body remain naked and unclothed and keep its splendor and its beauty intact.”

The second misconception is that it is necessary to study the nude in order to paint the human person well in naturalistic styles. While there are methods of study that do require the artist to understand anatomy, there are alternatives. I remembered my time studying at a studio in Florence where I learned the academic method, a way of painting that developed first during the High Renaissance. Although we did study the nude daily, we used a method called sight-size, in which we were taught to disregard our awareness of what we were looking at and consider only the shapes in the abstract. In other words, we learned to paint accurately what we saw, not what we knew to be there. We did not build up a figure by first sketching a skeleton, then putting on muscles, skin, and finally clothes. Some other schools do this, but it wasn’t necessary. Our teacher explained that we were following the method of the school of 17th century Spanish baroque naturalism. In that era, the Church in Spain (in contrast with Italy), forbade nude models, and so artists such as Velazquez and Zurburan never studied the nude as part of their training. They seemed to do pretty well despite this supposed handicap!

|

| The Ecstasy of St Francis by Zurburan |

|

| Crucifixion by Velazquez |