In his great encyclical on Sacred Scripture, Providentissimus Deus, Pope Leo XIII writes:

Earlier this week at NLM, I discussed the astonishing exclusion of 1 Corinthians 11:27–29 from the postconciliar liturgy (Mass and Office), in spite of the fact that it had been present in many places in the preconciliar Mass and Office. Our astonishment will be all the more complete when we read St. Thomas’s probing comments on these verses.

And this brings us back to the heart of the problem: the desire to sweep under the rug the demanding message of 1 Cor 11:27–29, on the necessity of individual examination of conscience and a sincere turning away from mortal sin. Concerning this and other “hard teachings” of Scripture — passages included in the old lectionary but deemed “too difficult” for modern man and therefore excised from the revised one — Peter Kreeft has some incisive words:

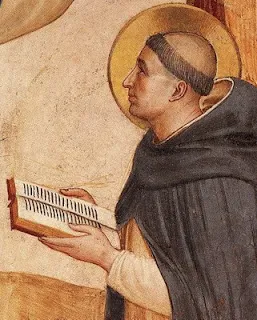

With the age of the scholastics came fresh and welcome progress in the study of the Bible. … The valuable work of the scholastics in Holy Scripture is seen in their theological treatises and in their Scripture commentaries; and in this respect the greatest name among them all is St. Thomas Aquinas. (n. 7)It is therefore with complete confidence that we can and should take up the Angelic Doctor’s commentaries on the Apostle to the Gentiles. These commentaries, from Aquinas’s maturest period, are some of the best reflections of his primary work as a Magister Sacrae Paginae at the university.

Earlier this week at NLM, I discussed the astonishing exclusion of 1 Corinthians 11:27–29 from the postconciliar liturgy (Mass and Office), in spite of the fact that it had been present in many places in the preconciliar Mass and Office. Our astonishment will be all the more complete when we read St. Thomas’s probing comments on these verses.

St Thomas Aquinas’s Commentary on 1 Corinthians 11:27–29

Therefore, whosoever shall eat this bread, or drink the chalice of the Lord unworthily, shall be guilty of the body and of the blood of the Lord. [nn. 687–94] But let a man prove himself: and so let him eat of that bread and drink of the chalice. [nn. 695–96] For he who eats and drinks unworthily eats and drinks judgment to himself, not discerning the body of the Lord. [n. 697]

687. After showing the dignity of this sacrament, the Apostle now rouses the faithful to receive it reverently. First, he outlines the peril threatening those who receive unworthily; second, he applies a saving remedy, at but let a man prove himself.

688. First, therefore, he says, therefore, from the fact that this which is received sacramentally is the body of Christ and what is drunk is the blood of Christ, whosoever shall eat this bread, or drink the chalice of the Lord unworthily, shall be guilty of the body and of the blood of the Lord.

In these words must be considered, first, how someone eats or drinks unworthily. According to a Gloss this happens in three ways.

First, as to the celebration of this sacrament, namely, because someone celebrates the sacrament in a manner different from that handed down by Christ; for example, if he offers in this sacrament a bread other than wheaten or some liquid other than wine from the grape of the vine. Hence it is said that Nadab and Abihu, sons of Aaron, offered before the Lord “unholy fire, such as he had not commanded them. And fire came forth from the presence of the Lord and devoured them” (Lev 10:1).

689. Second, from the fact that someone approached the Eucharist with a mind not devout. This lack of devotion is sometimes venial, as when someone with his mind distracted by worldly affairs approaches this sacrament habitually retaining due reverence toward it; and such lack of devotion, although it impedes the fruit of this sacrament, which is spiritual refreshment, does not make one guilty of the body and blood of the Lord, as the Apostle says here. However, a certain lack of devotion is a mortal sin, i.e., when it involves contempt of this sacrament, as it is said: “but you profane it when you say that the Lord’s table is polluted and its food may be despised” (Mal 1:12). It is of such lack of devotion that the Gloss speaks.

690. In a third way someone is said to be unworthy, because he approaches the Eucharist with the intention of sinning mortally. For it is said: “he shall not approach the altar, because he has a blemish” (Lev 21:23). Someone is understood to have a blemish as long as he persists in the intention of sinning, which, however, is taken away through penitence. By contrition, indeed, which takes away the will to sin with the intention of confession and making satisfaction, as to the remission of guilt and eternal punishment; by confession and satisfaction as to the total remission of punishment and reconciliation with the members of the Church. Therefore, in cases of necessity, as when someone does not have an abundance of confessors, contrition is enough for receiving this sacrament. But as a general rule, confession with some satisfaction should precede. Hence in the book On Church Dogmas it says: “One who desires to go to communion should make satisfaction with tears and prayers, and trusting in the Lord approach the Eucharist clean, free from care, and secure. But I say this of the person not burdened with capital and mortal sins. For the one whom mortal sins committed after baptism press down, I advise to make satisfaction with public penance, and so be joined to communion by the judgment of the priest, if he does not wish to receive the condemnation of the Church.”

691. But it seems that sinners do not approach this sacrament unworthily. For in this sacrament Christ is received, and he is the spiritual physician, who says of himself: “those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick” (Matt 9:12). The answer is that this sacrament is spiritual food, as baptism is spiritual birth. But one is born in order to live, but he is not nourished unless he is already alive. Therefore, this sacrament does not befit sinners who are not yet alive by grace; although baptism befits them.

Furthermore, as Augustine say in his Commentary on John, “the Eucharist is the sacrament of love and ecclesial unity.” Since, therefore, the sinner lacks charity and is deservedly separated from the unity of the Church, if he approaches this sacrament, he commits a falsehood, since he is signifying that he has charity, but does not. Yet because a sinner sometimes has faith in this sacrament, it is lawful for him to look upon this sacrament, which is something absolutely denied to unbelievers, as Dionysius says in Ecclesiastical Hierarchy.

692. Second, it is necessary to consider how one who receives this sacrament unworthily is guilty of the body and blood of the Lord. This is explained in three ways in a Gloss.

In one way materially: for one incurs guilt from a sin committed against the body and blood of Christ, as contained in this sacrament, which he receives unworthily and from this his guilt is increased. For his guilt is increased to the extent that a greater person is offended against: “how much worse punishment do you think will be deserved by the man who has spurned the Son of God and profaned the blood of the covenant?” (Heb 10:29).

693. Second, it is explained by a similitude, so that the sense would be: he shall be guilty of the body and of the blood of the Lord, i.e., he will be punished as if he had killed Christ: “they crucify the Son of God on their own account and hold him up to contempt” (Heb 6:6). But according to this the gravest sin seems to be committed by those who receive the body of Christ unworthily. The answer is that a sin is grave in two ways: in one way from the sin’s species, which is taken from its object; according to this a sin against the godhead, such as unbelief, blasphemy and so on, is graver than one committed against the humanity of Christ. Hence, the Lord himself says: “whoever says a word against the son of man will be forgiven; but whoever speaks against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven” (Matt 12:32). And again a sin committed against the humanity in its own species is graver than under the sacramental species.

In another way, the gravity of sin is considered on the part of the sinner. But one sins more, when he sins from hatred or envy or any other maliciousness, as those sinned who crucified Christ, than one who sins from weakness, as they sometimes sin who receive this sacrament unworthily. It does not follow, therefore, that the sin of receiving this sacrament unworthily should be compared to the sin of killing Christ, as though the sins were equal, but on account of a specific likeness: because each concerns the same Christ.

694. He shall be guilty of the body and of the blood of the Lord is explained in a third way, i.e., the body and blood of the Lord will make him guilty. For something good evilly received hurts one, just as evil well used profits one, as the sting of Satan profited Paul.

By these words is excluded the error of those who say that as soon as this sacrament is touched by the lips of a sinner, the body of Christ ceases to be under it. Against this is the word of the Apostle: whosoever shall eat this bread, or drink the chalice of the Lord unworthily. For according to the above opinion, no one unworthy would [be able to] eat or drink. But this opinion is contrary to the truth of this sacrament, according to which the body and blood of Christ remain in this sacrament, as long as the appearances remain, no matter where they exist.

695. Then when he says, but let a man prove himself, he applies a remedy against this peril. First, he suggests the remedy; second, he assigns a reason, at for he who eats; third, he clarifies the reason with a sign, at therefore, there are many.

696. First, therefore, he says: because one who receives this sacrament unworthily incurs so much guilt, it is necessary that a man first examine himself, i.e., carefully inspect his conscience, lest there exist in it the intention to sin mortally or any past sin for which he has not repented sufficiently. And so, secure after a careful examination, let him eat of that bread and drink of the chalice, because for those who receive worthily, it is not poison but medicine: “let each one test his own work” (Gal 6:4); “examine yourselves to see whether you are holding to your faith” (2 Cor 13:5).

697. Then when he says, for he who eats, he assigns the reason for the above remedy, saying: a previous examination is required, for he who eats and drinks unworthily eats and drinks judgment, i.e., condemnation, to himself: “those who have done evil will rise to the resurrection of judgment” (John 5:29). Not discerning the body of the Lord, i.e., from the fact that he does not distinguish the body of the Lord from other things, receiving him indiscriminately as other foods: “anyone who approaches the holy things while he has an uncleanness, that person shall be cut off from my presence” (Lev 22:3).

* * *

In the foregoing text, we see St. Thomas Aquinas lucidly expounding 1 Cor 11:27–29 in accord with the great majority of Catholic theologians and magisterial documents down through the ages. In striking contrast, we find Pope Francis in Amoris Laetitia stating outright (as modern scriptural exegetes are wont to do) that vv. 27–29 are more correctly interpreted in a social sense, in accord with the context of 1 Cor 11:17–34; indeed he goes so far as to dismiss the traditional reading as being out of context and generic. Pay careful attention to n. 186:Pope Francis’s Commentary on 1 Corinthians 11:27–29

185. Along these same lines, we do well to take seriously a biblical text usually interpreted outside of its context or in a generic sense, with the risk of overlooking its immediate and direct meaning, which is markedly social. I am speaking of 1 Cor 11:17–34, where Saint Paul faces a shameful situation in the community. The wealthier members tended to discriminate against the poorer ones, and this carried over even to the agape meal that accompanied the celebration of the Eucharist. While the rich enjoyed their food, the poor looked on and went hungry: “One is hungry and another is drunk. Do you not have houses to eat and drink in? Or do you despise the Church of God and humiliate those who have nothing?” (vv. 21-22).

186. The Eucharist demands that we be members of the one body of the Church. Those who approach the Body and Blood of Christ may not wound that same Body by creating scandalous distinctions and divisions among its members. This is what it means to “discern” the body of the Lord, to acknowledge it with faith and charity both in the sacramental signs and in the community; those who fail to do so eat and drink judgement against themselves (cf. v. 29). The celebration of the Eucharist thus becomes a constant summons for everyone “to examine himself or herself” (v. 28), to open the doors of the family to greater fellowship with the underprivileged, and in this way to receive the sacrament of that eucharistic love which makes us one body. We must not forget that “the ‘mysticism’ of the sacrament has a social character” (Pope Benedict XVI). When those who receive it turn a blind eye to the poor and suffering, or consent to various forms of division, contempt and inequality, the Eucharist is received unworthily. On the other hand, families who are properly disposed and receive the Eucharist regularly, reinforce their desire for fraternity, their social consciousness and their commitment to those in need.

* * *

Now, it requires no special expertise to see that a social reading of 1 Cor 11:27–29 and a moral-dogmatic reading of it are not incompatible; indeed, it is part of the genius of St. Paul that he often interweaves the communal, the spiritual, and the sacramental. The problem consists rather in the downplaying or sidelining of the dominant traditional reading in a document tackling the thorny question — debated intensely now for some time — of who should and should not be admitted publicly to the banquet of the Holy Body and Blood of Christ. The classic interpretation of this passage, epitomized in the Church’s Common Doctor, is particularly relevant and profoundly needed in our times. A refusal to pay heed to it, or, worse, a dismissive attitude towards it, is symptomatic of precisely that hermeneutic of rupture and discontinuity so keenly diagnosed by Pope Benedict XVI.And this brings us back to the heart of the problem: the desire to sweep under the rug the demanding message of 1 Cor 11:27–29, on the necessity of individual examination of conscience and a sincere turning away from mortal sin. Concerning this and other “hard teachings” of Scripture — passages included in the old lectionary but deemed “too difficult” for modern man and therefore excised from the revised one — Peter Kreeft has some incisive words:

We want it all. We want God and… But we can’t have God and… because there is no such thing. The only God there is, is “God only,” not “God and.” God is a jealous God. He himself says that, many times, in his word. He will not share our heart’s love with other gods, with idols. He is our husband, and his love will not tolerate infidelity. A hard saying, especially to our age, which is spiritually as well as physically promiscuous. But if we find the saying hard, that is all the more reason to look at it again and look at ourselves in its light, for the fact that we find it hard means that we have not accepted it yet, and need to. It’s precisely those parts of God’s revealed word that we don’t like or understand that we need to pay the most attention to. (Making Choices: Practical Wisdom for Everyday Moral Decisions [Ann Arbor, MI: Servant Books, 1990], 151)