Mons. Luzzi, bishop of Todi, distributing Communion in 1888, watercolour, canon’s sacristy, Todi cathedral

Mons. Luzzi, bishop of Todi, distributing Communion in 1888, watercolour, canon’s sacristy, Todi cathedralThis small watercolour is kept in one of the rooms of the canon’s sacristy of Todi cathedral, and is an

ex voto for the restored health of Msgr. Luzzi (Bishop of Todi from 1882–1888); as a small printed label relates: Al SS. Cuore di Gesù in ringraziamento della guarigione di S.E.R.ma Monsignor Luzzi vescovo di Todi il giorno 5 Maggio 1883.

The small painting is interesting as it shows what communion was like in the late 19th century and up to the first quarter of the 20th century. Shown in the painting is a typical “Comunione generale di devozione” which generally took place outside the rite of the Mass, after Forty Hour devotions or a Triduum.

The rite is taking place within Todi cathedral and in front of a temporary altar erected for the feast of the Madonna del Campione, a much loved and venerated image of the Blessed Virgin, so called because it stood in a small oratory in the portico of the medieval city hall, where was kept the public sample, or Campione, of the weights and measures in use in Todi.

On the 24th of July, 1796, during the anti-Christian persecutions of the French Jacobins, the Madonna was seen by the population to miraculously open, close and move her eyes for several days. Since then, every year in May the image of the Madonna del Campione is taken in procession from its chapel under the municipal palace to the Cathedral where it stays until the 25th of July, thus encompassing also the feast of the Sacred Heart. For this occasion a “macchina,” or temporary altar, with the venerated image of the Madonna is erected in the nave of the cathedral.

There are several interesting things to note within the painting.

In the first place, there is the fact that communion is evidently a particularly important and exceptional rite. Communion as practiced today is essentially due to St. Pius X’s encouragement of frequent communion but before then, communion was sparingly given and almost all faithful communicated only at Easter (the “precetto Pasquale”) and perhaps one or two times a year. In the late 18th century frequent communion meant once a month. Msgr. Barbier de Montault’s

Année liturgique à Rome (1862 and 1870) lists the few Roman churches where general communion was distributed, showing that generally communion was not included in ordinary Masses. In fact, very often communion, especially at Easter, was not part of the Mass: the faithful would go to confession in Lent or Easter and a priest distributing communion would be placed immediately next to the confessional so that penitents passed directly from confession to communion without time to sin! Generally speaking, in the past one would go often to confession and rarely to communion, whereas now it is the opposite. All this contributed to the reverence, sacrality, and exceptional importance of holy communion.

As the altar of the Madonna del Campione was a temporary one, there is no balustrade, but a kneeler covered with red cloth or velvet and with cushions; ladies (it is traditionally thought that the ladies represented are actual portraits of some of the most pious of the local noblewomen), widows clad in black, and women of the people, are kneeling or approaching to receive communion. This is solemnly distributed by Bishop Luzzi, who is wearing a gold chasuble and his pectoral cross, assisted by a chaplain in the very short, 18th century Roman style surplices, holding the paten, and by the canons of the cathedral in violet mozzette, short rochets and black cassocks; one is holding the ombrellino as the communion is taking place outside the sanctuary and therefore the canons accompanied the bishop to the altar of the Sacrament to take the pyx with the Blessed Sacrament back to the temporary altar of the Madonna del Campione. Another minister kneels nearby and six altar boys in Roman surplices kneel on the side next to the two Gentiluomini (Gentlemen) of the bishop’s court in black ferraiolos draped around the waist and formal black dress (probably tails or a frock coat; this last considered at the same level of formality as white tie), one holding the silver ewer and basin used for the bishop’s lavabo, whereas the other must have been holding the towel; they are not wearing the 17th century “abito di città” as this ceremony was not of the highest formality. The Mass just celebrated must have been a

Missa praelatitia of a certain solemnity with the assistance of the canons but without deacon and subdeacon. On the altar can be seen a set of small altar cards, the chalice with purificator, and the veil.

The altar has an antependium and apparently only a very short altar cloth edged with lace (but it is probably only the upper cloth); the sides of the altar are covered by a laceless altar cloth. Short altar cloths that did not cover the sides of the altar entirely were reserved for funerals, but often this was disregarded despite the prescriptions of liturgists and repeated decrees of the Sacred Congregation of Rites. As such, short altar cloths edged with higher and higher lace (generally machine lace, often very beautiful) became very common, especially in the 19th century.

The gradine and tabernacle (open, as it is a bishop’s Mass and the Blessed Sacrament was reserved elsewhere) are evidently designed to support the devotional image of the Sacred Heart. Extra candles are on small sconces as the feast took place during the permanence of the B.V. del Campione in the cathedral. Note the small crucifix on its summit; as the image occupied the place of the cross on the gradine, and as Mass couldn’t be celebrated without one, the legalistic 18th century solution was to place a tiny crucifix wherever possible, on top of altar images, frames, even on the top of altarpieces high up.

The six large candlesticks alternate with four “portapalme”, vases or urns made to support “palme,” literally palms, which were bouquets of artificial silk flowers or almond shaped embossed metal bouquets.

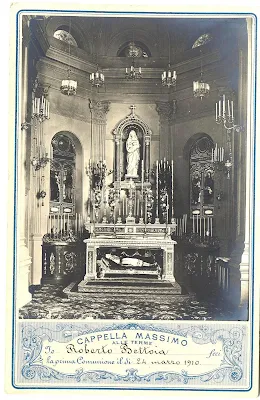

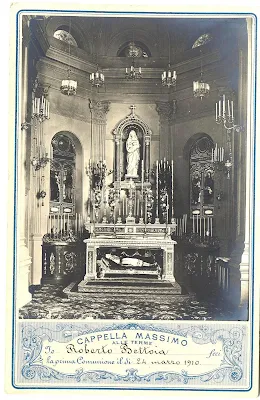

Collegio Massimo, Rome, chapel, c. 1879. The Collegio Massimo was founded by Fr. Massimiliano Massimo S.J., a member of a princely Roman family, and was the aristocratic boy’s school in Rome. The chapel is typical of elegant private chapels in Rome and shows portapalme in the context for which they were meant. Note the very tall portapalme of silk flowers with satin ribbons of the stem, the reliquary set on a small urn also containing relics in front of the crucifix. There is no tabernacle as the Sacrament would have not been reserved there. The large amount of sconces for candles, the torchères and the chandeliers are meant for Benediction, which would have taken place there. The altar contains the intact body of a martyr, which was a must for prestigious private chapels, and very probably named St. Massimo after the school. The actual relics would have been enclosed in a small coffer inside the representation of the body, with wax head and limbs. The small lamps at the foot of the urn would have been kept burning in his honour. It is likely that normally the urn with the martyr would have been covered by an antependium. The luxurious carpeting is of the sort that would have been used in drawing rooms of a 19th century style that has become traditional for church carpets for ceremonies. Note also the fitted carpet with the rich border on the steps. This chapel, which is in a typically Roman late classicist style, no longer exists as the Collegio Massimo has relocated and the building is actually the Roman museum.

Collegio Massimo, Rome, chapel, c. 1879. The Collegio Massimo was founded by Fr. Massimiliano Massimo S.J., a member of a princely Roman family, and was the aristocratic boy’s school in Rome. The chapel is typical of elegant private chapels in Rome and shows portapalme in the context for which they were meant. Note the very tall portapalme of silk flowers with satin ribbons of the stem, the reliquary set on a small urn also containing relics in front of the crucifix. There is no tabernacle as the Sacrament would have not been reserved there. The large amount of sconces for candles, the torchères and the chandeliers are meant for Benediction, which would have taken place there. The altar contains the intact body of a martyr, which was a must for prestigious private chapels, and very probably named St. Massimo after the school. The actual relics would have been enclosed in a small coffer inside the representation of the body, with wax head and limbs. The small lamps at the foot of the urn would have been kept burning in his honour. It is likely that normally the urn with the martyr would have been covered by an antependium. The luxurious carpeting is of the sort that would have been used in drawing rooms of a 19th century style that has become traditional for church carpets for ceremonies. Note also the fitted carpet with the rich border on the steps. This chapel, which is in a typically Roman late classicist style, no longer exists as the Collegio Massimo has relocated and the building is actually the Roman museum.

These embossed metal palms are extremely stylized representations of bouquets of flowers which were arranged in a very symmetrical composition. This kind of palma, or even imitations of sprays of flowers, were also often made in silver and in silver filigree, but these are extremely rare after the French invasion and sacking of Italy.

S. Maria degli Angeli, Rome. This picture of a fashionable marriage being celebrated by a cardinal in the 1930's shows a richly decorated altar, both with fresh flowers and with no less than six large embossed metal portapalme (the normal number was four). The portapalme are probably 18th century, but the same models went on being made well into the 19th century

S. Maria degli Angeli, Rome. This picture of a fashionable marriage being celebrated by a cardinal in the 1930's shows a richly decorated altar, both with fresh flowers and with no less than six large embossed metal portapalme (the normal number was four). The portapalme are probably 18th century, but the same models went on being made well into the 19th century Parish of the Ss. Trinità dei Pellegrini, Rome, palma and portapalma, embossed and gilt copper, 18th century

Parish of the Ss. Trinità dei Pellegrini, Rome, palma and portapalma, embossed and gilt copper, 18th century Portapalma in gilt and carved wood with heraldic star, late 17th – early 18th century; palma in embossed and silvered copper, 18th century

Portapalma in gilt and carved wood with heraldic star, late 17th – early 18th century; palma in embossed and silvered copper, 18th century

Readers of this site might be familiar with these last as they are often in use at Ss. Trinità dei Pellegrini in Rome.

Porto Maurizio co-cathedral, main altar with carved and gilt wood palms, c. 1820; note the very large ones to the sides of the altar

Porto Maurizio co-cathedral, main altar with carved and gilt wood palms, c. 1820; note the very large ones to the sides of the altar

Sometimes portapalme were fashioned in gilt wood, and also gilt and decorated in black and gold for funerals. Palme were even fashioned to hold relics at the center of the flowers.

Fresh flowers were generally considered not in the best of taste, in part because decaying flowers were a well known emblem of mortality and vanity, whereas artificial flowers carried an idea of eternity and Paradise. But it must be said that fresh flowers were often used also.

Sicilian Capuchins were specialized in the production in palms made with silk flowers, besides candlesticks and other liturgical objects made in straw, which were to be used during Lent, as a exercise in patience. Nuns were also specialized in the production of these delicate and elegant objects. Real palms are used on Palm Sunday, and palms and flowers were removed from the altars during Advent and Lent.

Palma, Murano glass beads on metal wire, late 19th century. A rather battered example of a kind of palm that was very common in Italy

Palma, Murano glass beads on metal wire, late 19th century. A rather battered example of a kind of palm that was very common in Italy Portapalma, gilt wood, 1820's; palma, painted tole, late XIX c. This kind of metal palm, that could be very large, copied the more expensive but perishable silk flowers.

Portapalma, gilt wood, 1820's; palma, painted tole, late XIX c. This kind of metal palm, that could be very large, copied the more expensive but perishable silk flowers.

By the mid 19th century very tall bouquets of artificial flowers crafted in painted metal or tiny Murano glass beads were fashionable (I have been told that these last could also be in the different liturgical colours), but the more common type was like the one shown in our painting, highly stylized, almond shaped bouquets -- the almond shape edged with silver or gold lace/silk, with silk flowers and leaves disposed in a regular pattern within the almond, interspersed with gold and silver filigree, lace and decoration. Coloured and gilt paper were also frequently used in these productions. Due to their perishability, almost none of these have survived. This is the type of palma on the altar, and also on the side altar in the background -- which, by the way, also has a throne for benediction.

Oratory of St. Lawrence, Crosa, Valsesia, palma, gilt and printed paper, muslin, mid 19th century. This is an exceptionally rare survival of what was a fairly common model of palma, here fashioned in cheap materials: muslin instead of silk, gilt paper instead of gold lace, printed paper instead of silk or damasked ribbons

Oratory of St. Lawrence, Crosa, Valsesia, palma, gilt and printed paper, muslin, mid 19th century. This is an exceptionally rare survival of what was a fairly common model of palma, here fashioned in cheap materials: muslin instead of silk, gilt paper instead of gold lace, printed paper instead of silk or damasked ribbons

Behind the altar rises the imposing wooden architectural structure supporting the image of the B.V. del Campione, consisting of a large classical pedestal with classical decorations and six candles on gilt sconces. The image is surrounded by draperies, no doubt descending from a royal crown. An architectural exedra or apse with green damask panels, terminating with Corinthian pillars supporting an entablature, encircles the pedestal. All this was part of the temporary structure built each May for the feast of the Madonna.

This small painting shows the reverence, liturgical pomp, and solemnity that accompanied the distribution of the Blessed Sacrament by a bishop in his own cathedral, and also many other traditional usages and details which have now almost universally disappeared.

My thanks to Don Alessandro Fortunati Celembrini of the clergy of Todi for showing me the painting described in this paper, and for the information on the feast do the Madonna del Campione, I thank the Rev. Don Roberto Collarini, Provost of Varallo, and the Prior (churchwarden) of Crosa, Mr. Roberto Chiocca for allowing me to study the palms of the Oratory of Crosa. My special thanks to Gregory DiPippo for his valuable comments and information.