[The following two part series arose out of some historical photographs -- to be featured in the second part of this series -- which showed a form of clerical dress that many of us may not be familiar with. Rather than simply post some of these historical photographs with little in the way of comment, I asked Maurizio Bettoja in Rome if he could also provide us with some historical background on the subject -- which he gratefully has. Here is part one of that commentary.]

NLM Guest article by Maurizio Bettoja

Preface

Wearing an identifiable form of clerical dress has always been prescribed by the Church and, today, the wearing of the cassock at all times has become a symbol of strong priestly identity and attachment to tradition -- particularly in the light of the abandonment of clerical dress altogether by many since the time of the Council.

It is interesting to note, however, that the use the cassock, originally a late Roman, medieval magistrate’s garment, has seen an evolution in the past 150 years up to the present day; an evolution which many might find surprising. From the point of view of history, many of us may not be aware that a little more than a century ago the cassock was used only within liturgical, ceremonial or courtly contexts, and was not worn in day to day clerical life. Day to day usage dates only from the turn of the 19th century following from the French usage since the time of the 1789 revolution. Ironically then, the day to day usage which is today considered such a strong symbol of tradition was at one time considered quite differently.

It is important to state from the outset that the intent of this article is not to disparage the use of the cassock as we see it today. Instead, its purpose is simply to offer a historical consideration, illustrating the traditional, pre-late 19th century logic of having liturgical and ceremonial dress distinct from every day clerical dress, attempting to describe what was worn by the clergy previous to the change of dress in late 19th century, as shown from a set of 1860-1880 photographs of Roman society, and from contemporary prints and paintings.

We shall begin with the latter.

Part One

From the Roman diary of Prince Don Agostino Chigi:

1848, February - Sunday 6 — "In the last few days several ecclesiastics, including some belonging to the Chapter of St. Peter, having appeared in public wearing a round hat (in place of the ordinary three cornered one) with a short brim and a hanging cord, the Cardinal Vicar, by an order affixed in all sacristies, has forbidden any innovation in priest’s dress."

1850, June - Monday 17 — "It is given for certain, that the plan to have the Sacred College and all the Clergy adopt the cassock as their ordinary dress has been excluded, and it seems it will be spoken of no more."1

What is considered more ostensibly “traditionalist” than the Roman hat and cassock? Yet in the conservative, traditional Rome of the mid-nineteenth century, both were a shocking French liberal, modern innovation, to be vigorously resisted.

The ordinary dress for clergy and prelates in Rome and the rest of Italy was the so called abito corto or abito d’abate (short dress or priest’s dress: abate meant priest), essentially a 17th-18th century knee-length black wool dress which had crystallized and stopped evolving, with knee breeches, buckled shoes, and a short ferraiolo. This dress was the appropriate one even for cardinal’s private audiences with the Pope, while in public audience they would wear choir dress. Gaetano Moroni, in his famous Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiastica (Venice 1840-1865-1879) mentions cardinals visiting sovereigns in abito corto. The abito corto was universally worn by all ranks of clergy except religious. Before the late 19th century, priests generally wore the abito corto as the proper dress outside of the liturgy: the cassock, being a more formal attire than the abito corto, was reserved for the sacred liturgy and ceremonial occasions. The cassock, worn as choir dress, was called abito di formalità, formal dress.

The abito corto was a more austere version of the formal dress of gentlemen in the 17th century. The abito di città (town dress, also known as abito di spada, sword dress), the formal or court dress of the laity in Italy, was very similar, being entirely black and including the ferraioletto or ferraiolone (a longer ferraiolo), a knee-length coat, a waistcoat, silver or jewelled buttons and buckles, a lace collar or facciole consisting of two strips of muslin or lace, of 17th century origin and worn over the waistcoat and not under like the clerical collaro, lace cuffs, knee breeches, a sottanella or short skirt, buckled shoes and sword. It remained in use generally until circa 1848, and continued to be worn in the Papal court until the time of Paul VI.

The facciole were the lengthening of the points of collars, which took place in the 17th century, edged and later almost substituted with lace. The cambric facciole or rabat were traditionally worn in France by the clergy.

A priest in abito corto, ferraioletto (the lapels of the ferraioletto are visible over his shoulders, and the bottom of its cape can be seen hanging slightly longer than his coat) and Roman three cornered hat, from Msgr. Barbier de Montault’s Le coutume et les usages ecclesiastiques selon la tradition Romaine, Paris, 1897-1901

His Serene Highness prince Don Domenico Napoleone Orsini (1868 + 1947), hereditary Prince Assistant to the Holy See (from the Orsini family website). He is wearing the abito di città or abito di spada, almost identical to the abito corto, except for the short skirt or sottanella, the facciole or lace collar, consisting of two separate rectangular strips of lace or muslin, lace cuffs, steel buttons and buckles, and the sword. His very high rank is indicated by the velvet, silk and lace of the costume, and especially by the long ferraiolo or ferraiolone (similar to the ferraiolo worn with the abito Piano), trimmed all the way down with lace flounces in the mid-XVII c. style. This was the court dress worn by the highest lay offices of the papal Court; the rather theatrical neo-renaissance costume of the lay Camerieri Segreti di Cappa e Spada (Papal chamberlains) was invented under Pius IX in the late 1840s, whereas before they wore the ordinary court costume, the abito di città.

Cardinal Ottaviani’s gentiluomo, 1956.

The photograph is far from clear, but the costume is identical to prince Orsini’s costume, but with several simplifications, the principal being that the ferraiolo is a ferraioletto and therefore shorter, the costume is black wool, and the buttons are black silk; being in a procession, he is holding the cardinal’s hat.

Cardinal Luigi Macchi (1832 + 1907) and his court, c. 1890. The cardinal is not wearing the pectoral cross, a late development.

Note, from left to right, the three footmen in livery with the traditional braid woven with the cardinal’s arms; the Caudatario (train bearer), holding the cardinal’s Roman three cornered hat; the Maestro di Camera (chamberlain), the cardinal, sitting on a tronetto, with at his back on the left (his right) the Coppiere (cup-bearer), and a second Gentiluomo on the right, both in abito di città; then the secretary, in nigris and silk ferraiolone, and the Uditore (legal adviser or lawyer, Uditore can also mean judge), and finally the Decano (butler), in white tie, knee breeches, ferraiolone, and buckled shoes, holding the galero. In the back row, possibliy the Maestro di Casa, and three Aiutanti di Camera (valets) in white tie and black waistcoat. The secretary, Maestro di Camera, and Decano all wear the black silk ferraiolone. A cardinal’s court was divided in the Anticamera Nobile (Maestro di Camera, presiding, Auditore, Segretario, Coppiere, Gentiluomini), Seconda Anticamera (Maestro di Casa, Caudatario, cappellano, Cameriere), and finally the Sala (Decano, Aiutanti di Camera, footmen and stables). A cardinal’s or prince’s court was also known as “famiglia”, literally family; another term was “casa”, literally house. The papal court is still called “famiglia or casa pontificia”.

The abito corto for ecclesiastics was a more sober, austere yet dignified version of a gentleman’s dress, but with several significant differences: in the first place it was completely black, without colour; the material was black cloth, never velvet or silk, except the ferraiolo for higher ranks of clergy; there was no lace collar, ruff, cuffs or cravat; buttons were in the same material of the dress, or silk if coloured for prelates, never silver, gold or jewelled; the sword was absent. Particularly significant, in ancién régime society, was the choice of simple black cloth, and the absence of lace: materials in that time, being extremely costly and precious, were closely associated with rank and splendor vitae: black cloth was therefore conspicuosly austere. The quality of materials was regulated according to rank: for instance, in Rome no ecclesiastic could wear velvet in any form except the Pope, who wore the winter red velvet mozzetta, and a very long red velvet cappa magna, which he wore only once a year, at Christmas.

This form of dress, dignified yet austere, and immediately recognizable as priestly, fulfilled the rules of the Tridentine council, which ruled that clerics had to dress in a dignified, sober, and priestly manner, leaving the exact form of dress to the diocesan bishop’s determination and local custom.

The abito corto was worn so universally that some priests would even commit the abuse of celebrating the liturgy with it, instead of wearing the cassock: nihil sub sole novi. In 1792, the Archpriest D. Cesare Bellini, parish priest of Cressa, near Novara, assured his bishop that in his parish “The abuse of celebrating Holy Mass without the cassock is never committed" -- which of course meant it wasn’t such a rare occurrence.

In fact, the abito corto would have been hidden by the albs which, up to the 1840s, were generally edged by low lace between three and, at the most, ten centimeters high, very often lined for protection against tears. Lace was hand made, and quite expensive at the time: lace fifteen or twenty centimeters high would have been a very costly luxury indeed.2 Another frequent abuse, especially in fashion conscious France, was priests wearing light colours and velvets and silks, rather than black cloth.

The cassock was not (and in Italy still is not) reserved exclusively for the clergy, but was (and still is) an essential element of the ceremonial dress for magistrates, lawyers, university professors, etc., and it includes a sash exactly like the ones worn by the clergy. This dress derives from magistrate’s dress of the late antiquity and middle ages. For instance, judges in Italy wear the cassock, complete with sash with tassels, under the toga or robone, and so do university professors.

A recent portrait of an Italian judge, by Andrei Dubinin.

He is wearing a black cassock with the facciole and a red sash with tassels under the red toga; on the table, a modified version of the doctoral biretta. This was the formal costume for judges in the states of the Royal House of Savoy, then of the Kingdom of Italy, and now of the Italian republic. He is wearing decorations on his cassock.

The biretta is also not an exclusively priestly headdress, but was the doctoral hat part of the ceremonial dress of all doctors of law, theology, medicine, etc. since the middle ages. Today’s judge’s and professor’s toques are a evolved version of the doctoral biretta.

The following prints illustrate the respective dress of doctors, graduates from the Bologna and Rome Collegiate Faculties of theology, medicine, law, and philosophy and show firstly a clerical, and then two lay graduates wearing the cassock and sash, and holding the biretta.

An ecclesiastic, collegiate graduate in theology, Bologna University. He is wearing a fur edged mozzetta, and holding the doctoral biretta in his hand; note the buckled shoes, always worn with formal dress. From Collectio legum et ordinationum de recta studiorum ratione editarum a SS. D. N. Leone XII P.M. et Sacram Congregatione studiis moderandis, Rome 1827 (from the author’s collection)

A layman collegiate graduate in law, medicine, philosophy or philology from Bologna University: the cassock, sash, and biretta is identical to that of priests, but has four arches. He is wearing the toga or robone over the cassock; the colour of the sash varied with the faculty, and was respecively light blue, red, green and white. Note the beretta with four arches held in his hand. From Collectio legum et ordinationum de recta studiorum ratione editarum a SS. D. N. Leone XII P.M. et Sacram Congregatione studiis moderandis, Rome 1827

A layman collegiate graduate in medicine from the Roman Archiginnasio. Note the almuce, identical to that of canons, the biretta, and the tassels on the sash. From Collectio legum et ordinationum de recta studiorum ratione editarum a SS. D. N. Leone XII P.M. et Sacram Congregatione studiis moderandis, Rome 1827

Up to 1870, the Senator of Rome wore a red cassock under the cloth of gold robone, with a red moiré silk sash with tassels (as can be seen in the Museo di Roma in Palazzo Braschi): this costume was identical to that of a cardinal, and it also included a red galero, exactly like a prelate’s or cardinal’s pontifical hat.

This shows that the cassock is not an exclusively clerical dress, but essentially a ceremonial dress common to clergy, magistrates, professors, and graduates, which paradoxically in its day made the abito corto much more ecclesiastical than the cassock.

Msgr. Barbier de Montault (1830 + 1901), the great historian, erudite and researcher of ecclesiatical custom, in Le coutume et les usages ecclesiastiques selon la tradition Romaine (Paris, 1897-1901), remarks: "The abito corto represents a specifically ecclesiastical costume…because it is totally different to secular dress and because it isn’t worn by anyone except the clergy"; for prelates "Their town dress - as opposed to travelling dress - is the same as that of the clergy’s except for the red piping on their breeches, waistcoat, and coat. Their stockings, collaro and skullcap remain red... In winter this costume is completed by a red or violet cape trimmed with gold braid".3

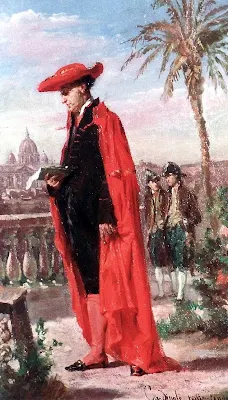

Cardinal in abito corto and tabarro walking in the Pincio public gardens. Note the red piping on his dress, and the gold braid on the tabarro; his footmen are following him. Etiquette forbade a prelate or magistrate of that rank to walk on his own, but had always to be accompanied by some member of his court. (The small painting is probably part of a series showing ecclesiastical and civil costume in Rome. These series, prepared for grand tourists and travellers since the early 19th century, showed all the principal personages and their dress in Rome, starting from the Pope and his Court, through cardinals and their Courts, the Senator of Rome, magistrates, the religious orders, etc.)

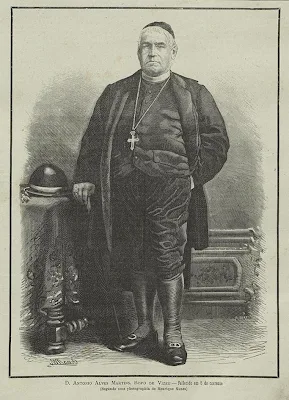

Mons. Antonio Alves Martins, bishop of Vizeu, c. 1870. Note the pectoral cross worn with the abito corto, and the “Roman”-French hat on the table.

It is not a coincidence that the introduction of the “Roman” (but really French) hat and cassock for all clergy should have happened in 1848, the year of revolution, and of the very anti-catholic democratic Roman Republic which followed: these new items of dress were strongly associated with French liberal catholicism.

In France after the revolution of 1789, the use of the cassock increased and became almost general by the mid-19th century.

Msgr. Barbier de Montault, writing in the 1890s, remarks "The abito corto is generally worn by the secular clergy, not only in Rome and throughout the whole of Italy, but also the world over, with the exception of France.".

It was the mildly liberal Pius IX who created the Pian dress (abito Piano), for cardinals and prelates private audiences with the decree Firma permanente (1851), which described the new dress which was supposed to replace the abito corto as an informal court dress; the Pope was aware of the cassock being already in general use in France.

This new dress was a mixture of the zimarra, a house dress resembling a buttoned dressing gown with a sleeved pellegrina4, choir dress, and the abito corto; of this last it retained the red or violet piping, ferraiolo (but in the form of the longer ferraiolone), collaro and stockings; the buckled shoes remained, as did the Roman three-cornered hat. The Pian dress also included one element of the choir dress, the sash, but abolishing the fiocchi or tassels and changing them into a fringe. This dress, according to Moroni, "could be used in private life."5

This decree remained largely a dead letter, both in Rome and in the rest of Italy: prelates and clergy continued wearing the abito corto until the turn of the century, and in a few cases well into the 1930's. Cardinal Pecci, the future Leo XIII, never stopped wearing the abito corto. Some earlier attempts to have the clergy wear the cassock at all times (e.g. by St. Charles Borromeo) had failed.

Pius IX’s measure caused discontent and a certain resistance, as it was felt most inappropriate that the clergy should wear for everyday use dress akin to what was normaly reserved for liturgy or ceremonies. It was argued that this was equivalent to be wearing white tie all the time, and – especially - it blurred the distinction between ordinary dress, and a dress of higher dignity (abito di formalità) reserved for the sacred liturgy and ceremonies. Msgr. Barbier de Montault deplored the wearing of the cassock in the streets, which he found very inappropriate.

Besides the strong attachment to traditional usage on the part of the clergy, there also were practical considerations to recommend the abito corto, which was easier to keep clean than the cassock in dusty or muddy roads, mostly unpaved at the time, especially for the lower clergy with pastoral care. This practical point was often brought up when earlier attempts had been made to impose the cassock as ordinary dress. It must be remembered that in the 1870s clothes, though not as costly as up to the XVIII c., were still quite expensive. If stained, almost the only method to clean cloth was by brushing, and a discoloured cassock could only be thrown away, if the stain couldn’t be brushed off.

It is only after 1870 and the loss of temporal power that the prelature started wearing the Pian dress more consistently; the Pope wished ecclesiatics to adopt a more priestly form of dress, after the loss of temporal power, and in a period of persecution of the Church. With the gradual disappearance of the abito corto at the Papal court, prelates began to drop the use of the abito corto, and also priests gradually followed suit and started to wear the cassock even when outside church and residence.

But already with the first Vatican Council there had been a French proposal for the universal use of the cassock, which show how little it was used: Nabuco (Ius pontificalium, Paris 1956) writes: “proposita in Concilio Vaticano quaestione de clericorum vestibus, episcopi Galliae usum vestium talarium ubique et semper ad universam Ecclesiam extendi voluere, sed eorum emendatio reiecta est”; the Council felt “non esse progrediendum ultra terminos Tridentinum Concilii, quae clericorum vestes vult esse honestas, a laicalibus distinctas, propriae dignitati et honori clericali congruentes, sed formam ipsam episcopi ordinationi et mandato determinandam reliquit”. Nevertheless the French influence spread, and by the end of the century the cassock and French round hat was being generally adopted everywhere. The traditional Roman three cornered hat went out of fashion even with Pian dress.

The Pian dress for prelates, and also for priests, thus became the informal court dress or “etiquette dress”, as Nainfa informs us (see Costume of Prelates of the Catholic Church according to Roman Etiquette, Baltimore, 1909), to be used "in all circumstances for which social customs and etiquette require the formal dress for a lay gentleman, namely visits, receptions, dinners, concerts, etc. It is also worn at Papal audiences…”

Whenever worn in the streets or outside of ceremonies, the cassock had to be covered by the clerical overcoat or greca, which originates in France at this time (the douillette) with the function of not exposing the cassock. This rule was reiterated even in John XXIII’s Roman synod of 1960.

But already in the ‘30s in some countries, like Germany, part of the clergy had stopped wearing the cassock in favour of clergy suits.

[This concludes part 1 of 2.]

Endnotes

1. Al tempo del Papa-Re: il diario del principe Don Agostino Chigi dall’anno 1830 al 1855, Milano 1966. A congregation of cardinals had discussed the adoption of the cassock for prelates and clergy.

2. Lace remained very expensive until the diffusion of machine made lace, in the 1840s, which caused lace prices to fall dramatically, which meant that albs, rochets and surplices could be garnished with very high lace of 60 cm. or more, made affordable by its industrial production. Before, the price of hand made lace that high would have fabulously expensive, running into the equivalent of tens of thousands of Euros, and could have been afforded only by very rich cardinals and prelates.

3. I wish to thank M. l’Abbé Brice Meissonnier, FSSP, president of the Societé Barbier de Montault, for his help regarding Msgr. Barbier de Montault’s works, and the prints and paintings of priests and prelates from his archives which he kindly sent to me.

4. Nabuco (Ius pontificalium, Paris 1956), writes: “Antiquitus extabat distinctio inter vestem talarem et togam aliam talarem quae zimarra nucupabatur. Vestis talaris erat potius pars habitus praelatitii seu di formalità, et contra zimarra erat vestis domestica ampla, cum supermanicis et parvo palliolo humerali pellegrina. Toga haec a Summo Pontifici (the white dress the Pope now wears almost always) et a romana praelatura adhibibatur domi et in privati receptionibus”

5. Thus Nabuco: “Sed tempora mutantur et Pio IX necessarium visum est ius novum instituere: vestes praelatitias pro functionibus sacris vel solemnioribus reservandas, aliumque habitum minus solemnen approbandum ad usum civilem seu extra liturgicum. Et sic in vita ecclesiastica introductus est habitus civilis seu in civilibus receptionibus, conventibus, commessationibus vel ceteris huiusmodi adhibendus, qui quidem habitus a Pio IX pianus nuncupabatur”