For terms and their definitions, please see the associated Glossary which accompanies this compendium.

Compendium of the Reforms of the Roman Breviary, 1568-1961

by Gregory DiPippo

for publication on the New Liturgical Movement

Part 5.1 - 1736: The Parisian Psalter

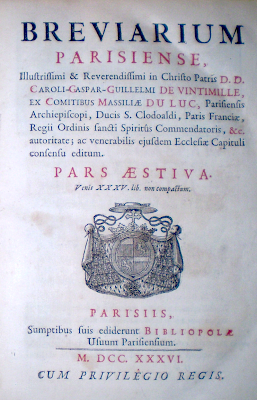

The term ‘Neo-Gallican’ is applied to the liturgical books used by a large number of French dioceses between 1667 and 1875, in place of the Roman liturgical books issued under the authority of Pope St. Pius V and his immediate successors. They are called ‘neo-Gallican’ by some modern liturgists to distinguish them from the Gallican liturgy once used in most of what is now called France, before Charlemagne imposed the use of the Roman Rite throughout his domains; there is no connection between the neo-Gallican uses and the pre-Carolingian liturgy. The first such Breviary was issued for use in the diocese of Paris in 1680; the last French diocese to abandon its home-made liturgical books in favor of the Roman use was Orleans, in 1875. (Right: Charles de Vintimille, Archbishop of Paris)

The term ‘Neo-Gallican’ is applied to the liturgical books used by a large number of French dioceses between 1667 and 1875, in place of the Roman liturgical books issued under the authority of Pope St. Pius V and his immediate successors. They are called ‘neo-Gallican’ by some modern liturgists to distinguish them from the Gallican liturgy once used in most of what is now called France, before Charlemagne imposed the use of the Roman Rite throughout his domains; there is no connection between the neo-Gallican uses and the pre-Carolingian liturgy. The first such Breviary was issued for use in the diocese of Paris in 1680; the last French diocese to abandon its home-made liturgical books in favor of the Roman use was Orleans, in 1875. (Right: Charles de Vintimille, Archbishop of Paris)It is beyond the purpose of this series of articles to give a detailed description of the neo-Gallican office. To do so would be to repeat, unnecessarily, the work of Dom Prosper Guéranger in the second volume of his famous Institutions Liturgiques. (http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/gueranger/institutions/) Dom Guéranger’s book was written in an avowedly polemical spirit, as part of his great and ultimately successful project to bring about the abolition of the neo-Gallican books, and a return to the unity of the Roman liturgical tradition. His assessment of the neo-Gallican use is generally negative; one of the headings to his first chapter about them is “the beginning of liturgical deviation in France.” More recent writers such as Msgr. Batiffol and Archdale King have been less harsh in their judgment. The latter offers a very useful summary of the whole movement in The Liturgies of the Primatial Sees, after his description of the ancient use of France ’s primatial see, Lyons , a use which was almost completely ruined by the neo-Gallicans.

If the purpose of this series were to give a more general history of recent liturgical reform, including the Missal along with the Breviary, and reaching into the post-Conciliar period, it would need to say a great deal more than I intend to about the neo-Gallican liturgy. The pages in which Mr. King describes its innovations to both Missal and Breviary could almost be a recipe book for the post-Conciliar rite. For the history of the Roman liturgy before the modern reform, however, there is one feature of the neo-Gallican use that is far more significant than all the rest.

The French vogue for liturgical reform did not begin in the capital, and it did not begin with a Breviary or a Missal, but rather with a Rituale published for the use of the clergy of Alet, in the southern Languedoc region. Paris did not lag far behind its distant province, though, and the first neo-Gallican revision of its Breviary was produced under the authority of Archbishop François de Harlay in 1680. Mr. King points out that these new books generally omitted from the frontispiece the words “ad formam sacrosancti concilii Tridentini emendatum – emended according to the form (laid down by) the sacred council of Trent .” Although many texts were changed, the Psalter was left in the traditional order in use since the 5th or 6th century, and present in the Breviary of St. Pius V with one minor modification.

If one Archbishop of Paris could arrogate to his office the right to re-edit the liturgical books used in his See without reference to the Roman authorities, there was no particular reason why subsequent Archbishops should not avail themselves of the same right. Consequently, the liturgical books of Paris went through multiple revisions between 1680 and their definitive abolition in 1873. The most momentous of these is the 1736 edition of Archbishop Charles de Vintimille, and not only because it remained in use as the Office of France’s capital for nearly a century and a half, and provided the model for breviary revisions of many other French dioceses. Far more importantly, it would later, in 1911, provide the model for the first significant change to the Breviary of St. Pius V after Pope Urban VIII’s revision of the hymns.

If one Archbishop of Paris could arrogate to his office the right to re-edit the liturgical books used in his See without reference to the Roman authorities, there was no particular reason why subsequent Archbishops should not avail themselves of the same right. Consequently, the liturgical books of Paris went through multiple revisions between 1680 and their definitive abolition in 1873. The most momentous of these is the 1736 edition of Archbishop Charles de Vintimille, and not only because it remained in use as the Office of France’s capital for nearly a century and a half, and provided the model for breviary revisions of many other French dioceses. Far more importantly, it would later, in 1911, provide the model for the first significant change to the Breviary of St. Pius V after Pope Urban VIII’s revision of the hymns.The ancient arrangement of the Psalter for Sundays and ferial days was designed around the recitation of the entire Book of Psalms over the course of a week. In an oft-quoted passage of his Rule, Saint Benedict says, “those monks show too lax a service in their devotion who in the course of a week chant less than the whole Psalter with its customary canticles; since we read, that our holy forefathers promptly fulfilled in one day what we lukewarm monks should, please God, perform at least in a week.” (chapter 18; transl. Rev. Boniface Verheyen, O.S.B.) Although the Roman Breviary and its allied uses had always maintained this tradition in theory, every feast day had proper psalms for Matins and Lauds, and almost always for Vespers. Thus, in reality, all the psalms were recited over the course of the week only in the very rare week in which no feasts at all occurred. This system was only very slightly changed by the reform of St. Pius V; recitation of the entire Psalter during any given week remained in practice an exception. It must also be kept in mind that in the traditional arrangement of the Psalter, the psalmody of Terce, Sext, None and Compline does not change from day to day, and that of Lauds and Prime changes but little; between them, these six hours contain only 25 of the psalms, the remaining 125 being divided unevenly between Matins and Vespers.

The Parisian Breviary of 1736 created an almost completely new arrangement of the Psalter for Sundays and ferial days, with the stated purpose of restoring the tradition of reciting the whole Psalter in a week. In order to do so, however, it was also necessary to extend the use of the ferial psalms to the Saints’ days; feasts are therefore divided into seven grades, and in all but the two highest, the psalms of the feria said at every hour. The ferial psalms are also said at first Vespers and the following Compline of the highest two grades of feasts, a custom observed in several medieval uses.

The new Parisian Psalter admits of no repetition at all among the psalms; each is said only once in the course of the week. Matins of Sunday is reduced from eighteen psalms to nine, and that of each feria from twelve to nine, conforming them to the pattern of Matins on feast days. The number of psalms at the other hours remains unchanged, and a canticle from the Old Testament is still said at Lauds after the third psalm. The extremely ancient custom of reciting psalms 148, 149 and 150 together as the last psalm of Lauds is done away with; however, it must be noted that the psalms chosen to replace them all begin with the word “Laudate” or “Lauda”.

There are 231 places for the psalms over the seven days of the week: nine each day at Matins, four at Lauds, five at Vespers, three each at the remaining Hours. There are, of course, only 150 psalms. In order to fill each of the 231 places, without repetitions, many of the longer psalms are divided into two or more sections, called “divisions” in the Parisian Breviary, as they are in the Benedictine. The psalms are not arranged in numerical order, as they are (broadly speaking) in the traditional Office; the psalms of Sunday Matins are 1, 2, 3, 17 (in three divisions), 27, 29, and 65. The rest of Sunday retains the order of the traditional rite, but Monday Matins has psalms 103, 104 and 105, moved from Saturday, each in three divisions; and so on. Msgr. Batiffol points out (p. 327) that each day is arranged around a theme, “on Sunday it is the idea of the love of God and the divine law; on Monday, God’s mercies; on the three succeeding days, charity towards one’s neighbor, hope, faith; on Friday patience (in memory of the Passion); on Saturday, thanksgiving.”

The traditional Old Testament canticles of Lauds are retained for use on the ferias, though three of them are moved to different days of the week. Some of these canticles are quite long, and were considered by the Parisian revisers to be inappropriate for feast days. Therefore, each day of the week also has a festal canticle for Lauds to be used in place of the traditional series. The complete re-ordering of the Psalter also necessitated a complete re-writing of the corpus of antiphons which accompany them; in general, the new antiphons are longer than the traditional ones of the Pian and medieval Breviaries. (It must be noted that all antiphons are always semi-doubled in the Parisian use.) Psalm 65, moved from Wednesday to Sunday, has an antiphon in the Pian Breviary, “Benedicite, gentes, Deum nostrum.”; its new Parisian antiphon is “Venite, audite, et narrabo quanta fecit animae meae.”

It is important to note that the antiphons of the Psalter are not said on the feasts of Saints. Instead, the ferial psalms are mixed with the antiphons of the feast, whether proper (as on Christmas) or taken from the common offices of the Saints; this or something similar to it was done in a number of medieval usages. The new Parisian use also maintained a common medieval custom (never observed in the use of Rome), whereby the psalms of Lauds and Vespers are said with only one antiphon on the lowest grades of feasts. The rubric “Concerning the Antiphons” is, not surprisingly, rather complicated.

Paris was not in fact the first French diocese to rearrange the Psalter. The Gallicanized Breviaries of Sens, (of which Paris had been a suffragan see until 1622,) of Nevers and of Rouen had all re-arranged the Psalter in a similar manner in the previous decade; indeed, much of the new Parisian arrangement is borrowed from the 1728 Rouen Breviary. The importance of the Parisian revision is that it almost immediately became the model for the reform of other Breviaries throughout France ; the Breviary of Blois, published at Paris the following year, borrows the Parisian Psalter in its entirety. The reform of the Roman Breviary by Pope St. Pius X, in 1911 will also borrow heavily from this new Parisian usage; it will be discussed in detail in an upcoming article in this series.

[This section will be completed in Part 5.2]

-- Copyright (c) Gregory DiPippo, 2009

To read previous installments in this series, see: Compendium of the Reforms of the Roman Breviary, 1568-1961