[The American Journal, Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, has published a piece by the the Prior of St. Michael's Abbey in California, Fr. Hugh Barbour, O.Praem, which touches into Pieperian and liturgical themes.]

by Fr. Hugh Barbour, O.Praem

“Go day, come day. Lord, send Sunday.” My paternal grandmother could be counted on to say these words at least once per week. Whether burdened with some mundane task or confronted with the evidence of human frailty, the prospect of the day of worship and witness, of rest and reading, of visiting and victuals was a precious consolation to her. Sunday reigned sovereign over the other days of the week, and the breach of its observance, whether by absence from church or by skimping on dinner or by mowing the lawn, was proof not only of infidelity, but of incivility. When local authorities began to permit Sunday openings, she saw through their pretense and predicted dire effects. “They think that they can steal time from the Almighty and that He won’t notice. But He’s the One who said ‘Six days shalt thou labor, and do all that thou hast to do; but the seventh day is the Sabbath of the LORD thy God.’ Soon enough and they’ll begin to think that they’re almighty themselves, but He’ll show them who’s the King.”

My grandmother was surely not a philosopher and even less a theologian. (Her best effort at showing some little appreciation of her grandson’s Catholicity was when she said, “The Roman religion is just too deep for me.”) Even so, her approach to time and work and worship was in line with the deepest of insights, in particular with those of the great German Thomist Josef Pieper, who, in the summer of 1947, presented a paper in Bonn entitled “Musse und Kult” (“Leisure and Worship”), known in English as Leisure, the Basis of Culture. The American edition of this conference, with a splendid Introduction by T.S. Eliot—a fine piece in its own right—was first published in 1952. Ever since, it has set the standard for contemporary treatments of the meaning of culture as cult—that is, as founded in the celebration of divine worship.

Pieper’s study hinges on several telling etymologies from which are to be unpacked all the implications of his theory of the essential form of human society. One is the Greek schole, which means “leisure”; from this word is derived the Latin schola and, hence, the English school, as well as its equivalents in all the Romance and Germanic languages. Regarding the leisure necessary for contemplation, Pieper writes:

“We work in order to have leisure.” . . . That maxim is not . . . an illustration invented for the sake of clarifying this thesis: it is a quotation from Aristotle; and the fact that it expresses the view of a cool-headed workaday realist (as he is supposed to have been) gives it all the more weight. Literally, the Greek says “we are unleisurely in order to have leisure.” “To be unleisurely”—that is the word the Greeks used not only for the daily toil and moil of life, but for ordinary everyday work.

“Greek,” Pieper points out, “only has a negative”—a-scholia—“just as Latin has neg-otium.” Another word is cultus, to which is related cultura and, evidently, culture and all its equivalents in other European languages. In his Preface to the American translation, Pieper points out:

The word “cult” in English is used exclusively, or almost exclusively, in a derivative sense. But here it is used, along with worship, in its primary sense. It means something else than, and something more than, religion. It really means fulfilling the ritual of public sacrifice. That is a notion which contemporary “modern” man associates almost exclusively and unconsciously with uncivilized, primitive peoples and with classical antiquity. For that very reason it is of the first importance to see that the cultus, now as in the distant past, is the primary source of man’s freedom, independence and immunity within society. Suppress that last sphere of freedom, and freedom itself, and all our liberties, will in the end vanish into thin air.

This characterization of freedom and liberty as the fruits of right worship directs our attention to a third telling etymology, that of the artes liberales, the “liberal arts.” Pieper clarifies the notion for us with arguments from great authorities, ancient and modern:

What are the liberal arts? In his commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics, Aquinas gives this definition: “Only those are called liberal or free which are concerned with knowledge; those which are concerned with utilitarian ends that are attained through activity, however, are called servile.” “I know well,” Newman says, “that knowledge may resolve itself into an art, and seminate in a mechanical process and in tangible fruit; but it may also fall back upon that Reason, which informs it, and resolve itself into Philosophy. For in one case it is called Useful Knowledge, in the other Liberal.” The liberal arts, then, include all forms of human activity which are an end in themselves; the servile arts are those which have an end beyond themselves, and more precisely an end which consists in a utilitarian result attainable in practice, a practicable result.

This third consideration, of the meaning of liberal, will shortly lead us to some progress in thought even beyond Pieper’s little—klein aber fein—masterpiece, but wholly in line with it. First, however, let us sum up his teaching: A true human society, a genuine culture, is based on those activities that are ends in themselves, which do not serve any purpose other than knowledge and love. Among these contemplative activities of free men possessing leisure time, the highest place, the one most formally determining of culture, is common worship, the celebration of the cultus of the Divinity, the sacrifice of praise, surely the most self-sufficient of human and social activities. The preeminent cultural form is, thus, the feast, the holy day, the Sabbath, the Lord’s Day, which, because of the Christian dispensation, in fact becomes every day, since on every day this worship is offered. Pieper sums up his high point:

The Christian cultus, unlike any other, is at once a sacrifice and a sacrament. Insofar as the Christian cultus is a sacrifice held in the midst of creation which is affirmed by the sacrifice of the God-man—every day is a feast day; and in fact the liturgy knows only feast days, even working days being feria . . . We hope . . . that in the performance of [Christian worship] man, “who is born to work” may be truly “transported” out of the weariness of daily labor into an unending holiday, carried away out of the straitness of the workaday world into the heart of the universe.

The grandeur of Pieper’s vision of human existence in society can hardly be overstated. He has pointed out the key to the sublimation of all our activities—not only of the necessarily servile arts that serve the others but of the sciences and philosophy—into an act of worship, which contains the praise of the whole creation under God. Even so, his vision can be transcended, for there is a more fundamental sense of the “liberal” of the utterly free and at ease, which underlies the whole, and goes beyond mere culture and even creaturely worship, by reaching the Source of all things whatsoever and indicating the attribute most characteristic, most proper to Him. In discussing whether God can be said to have the moral virtues that issue forth in action, St. Thomas Aquinas tells us in his Summa contra Gentiles I:xciii:

The ultimate end for which God wills all things in no way depends on the things that exist for the sake of that end, either in regard to being or to some particular perfection. Hence, He does not will to give someone His goodness so that thereby something may accrue to Himself, but because for Him to make such a gift befits Him as the fount of goodness. But to give something not for the sake of some benefit expected from the giving, but because of the goodness and appropriateness of the giving, is an act of liberality, as appears from the Philosopher in Ethics iv. God, therefore, is supremely liberal, and as Avicenna says, He alone can be properly called liberal, for every agent other than God acquires some good from his action, which is the intended end. Scripture sets forth the liberality of God, saying in a psalm “When thou openest thy hand, they shall all be filled with good” and in James “Who giveth to all men abundantly and upbraideth not.”

“God alone is supremely liberal . . . He alone can be properly, proprie, called liberal.” Quite simply, it is impossible for a creature to perform any good action, even the most lofty, without some kind of product—namely, the hitherto unattained end intended and gained by his action. Even if it is an end in itself, the action of one who—unlike God—is not identical with his own good brings about his own perfection and happiness, not to mention the merit that claims a reward in justice. But God acts without the least increase in His own perfection or happiness, gaining nothing, solely out of goodness, and so He alone is truly and properly, fully and perfectly free, liberal.

Aristotle already had a shadowy hint of an understanding of the ultimate sense of the service God’s intelligent creatures owe Him when, in the crowning considerations of his Metaphysics, he explains that the powers of heaven are drawn by the contemplation of the Supreme Good and Ultimate Final Cause of all things to the imitation of His causality, each having its own proper effect on the beings lower in the hierarchy of the cosmos. Aquinas, commenting on this passage, describes the purpose of their activity as one of assimilation, of becoming like the Good, by imitating His self-diffusive generosity ut assimilentur ei in causando. They become like Him by doing as He does, pouring out their inner riches of mind and will on those beneath them. In the Christian era, this office has not been left merely (what a bold “merely” that is!) to the angels, but has been extended through the Incarnation of God to men. They become “sharers in the divine nature” and form a nation of priests, prophets, and kings. Becoming images and likenesses of the divine liberality, the free and easy beneficence of God, then, is the end of those who contemplate in leisure the higher things and who, in worship, not only praise as creatures but pour out as priests the “good things to come.” There is a kind of paradox here, which, upon examination, is only a recapitulation on a higher level: The final perfection of contemplative leisure is an action, a work of generous liberality. Saint Paul reminds us of the words of Jesus: “It is more blessed to give than to receive.” Here is his meaning.

“It is better to give light than merely to burn.” This is Aquinas’ tag to introduce his rationale for the life of the apostle being higher in dignity than that of the mere contemplative, since the apostle not only gazes lovingly at the Good but bestows it on others. This is not the banal activism of the bored humanitarian; it is the intense, contemplative drive of one who has become like the One Whom he has contemplated in worship. As our Western world becomes more and more clearly the place of the sunset of all that is leisurely, free, and pious, it is this effect of the Christian cultus that must stand out more clearly: the love of neighbor as the visible sign of the love of God. We ourselves must give others the time, the liberty, and the sacred precinct to possess with us “the power to become the sons of God.” This is the needful liberality that must be the basis of culture. And all the more because it will only come about in those places where we ourselves undertake so great a work on so small a scale. The great workaday world is not going to do it for us. It will be for a time (please excuse the macaronic pun) the ultimate “home-schole”—and not only for children, but for our neighbors and friends; and not only for worship, but for everything human. Grandmother’s house on Sunday may be the very statio orbis for which we are looking.

There is a final caveat. Having contemplated the Good, and now returning to enlighten our fellow men, we may share the fate of the one who returned to the darkness of the Platonic cave to free those who know only shadows and who confuse words with realities. But then, did He not say, “and if I be lifted up from the earth I will draw all men unto Myself”? And is this not why our Sunday is a feast?

Fr. Hugh is prior of St. Michael’s Abbey in Trabuco Canyon, California.

Source: Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture | Your Home for Traditional Conservatism » Liberality, the Basis of Culture

Wednesday, August 22, 2007

Liberality, the Basis of Culture

Shawn TribeMore recent articles:

The Tomb of St Peter Martyr in Milan’s Portinari ChapelGregory DiPippo

Here are some great photos from our Ambrosian correspondent Nicola de’ Grandi of the Portinari Chapel at the Basilica of St Eustorgio in Milan. They were taken during a special night-time opening made possible by a new lighting system; as one might well imagine, the Italians are extraordinarily good at this sort of thing, and more and more museum...

Recommended Art History and Artistic Practice Text Books for Homeschoolers... and Everyone Else Too!David Clayton

I want to recommend the Catholic Heritage Currricula texts books to all who are looking for materials for courses in art history, art theory and artistic practice at the middle-school or high-school level. These books present a curriculum that combines art history, art theory, and a theory of culture in a Catholic way. Furthermore, they provide the...

Launching “Theological Classics”: Newman on the Virgin Mary, St Vincent on Novelty & Heresy, Guardini on Sacred SignsPeter Kwasniewski

At a time of turmoil, nothing could be better or more important than rooting ourselves more deeply in the Catholic tradition. One of my favorite quotations is by St. Prosper of Aquitaine (390-455), writing in his own age of chaos: “Even if the wounds of this shattered world enmesh you, and the sea in turmoil bears you along in but one surviving shi...

Low Sunday 2025Gregory DiPippo

With his inquisitive right hand, Thomas searched out Thy life-bestowing side, O Christ God; for when Thou didst enter while the doors were shut, he cried out to Thee with the rest of the Apostles: Thou art my Lord and my God. (The Kontakion of St Thomas Sunday at Matins in the Byzantine Rite.)Who preserved the disciple’s hand unburnt when he drew n...

The Easter Sequence Laudes SalvatoriGregory DiPippo

The traditional sequence for Easter, Victimae Paschali laudes, is rightly regarded as one of the greatest gems of medieval liturgical poetry, such that it was even accepted by the Missal of the Roman Curia, which had only four sequences, a tradition which passed into the Missal of St Pius V. But of course, sequences as a liturgical genre were extre...

The Paschal Stichera of the Byzantine Rite in EnglishGregory DiPippo

One of the most magnificent features of the Byzantine Rite is a group of hymns known as the Paschal stichera. These are sung at Orthros and Vespers each day of Bright Week, as the Easter octave is called, and thenceforth on the Sundays of the Easter season, and on the Leave-taking of Easter, the day before the Ascension. As with all things Byzantin...

Medieval Vespers of EasterGregory DiPippo

In the Breviary of St Pius V, Vespers of Easter Sunday and the days within the octave present only one peculiarity, namely, that the Chapter and Hymn are replaced by the words of Psalm 117, “Haec dies quam fecit Dominus; exsultemus et laetemur in ea. – This is the day that the Lord has made; let us be glad and rejoice therein.” In the Office, this...

Summer Graduate-Level Sacred Music Study - Tuition-freeJennifer Donelson-Nowicka

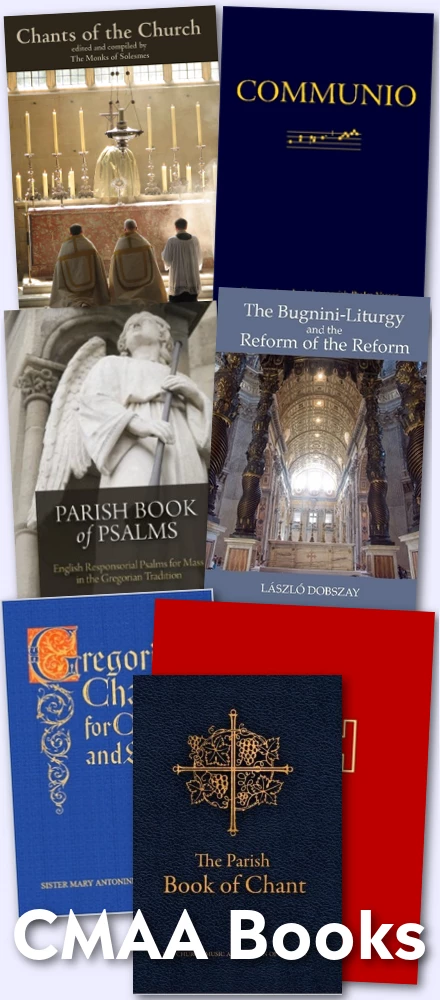

The May 1st application deadline is approaching for summer graduate courses in sacred music at the Catholic Institute of Sacred Music. Graduate-level study structured for busy schedulesIn-person, intensive course formatsAffordable room & boardFree tuitionLearn more and apply here.Courses:Choral InstituteComposition SeminarOrgan ImprovisationIn...

The Last Service of EasterGregory DiPippo

Following up on Monday’s post about the service known as the Paschal Hour in Byzantine Rite, here is the text of another special rite, which is done after Vespers on Easter day itself. It is brief enough to show the whole of it with just one photograph from the Pentecostarion, the service book which contains all the proper texts of the Easter seaso...

Should Communion Sometimes Be Eliminated to Avoid Sacrilege?Peter Kwasniewski

In a post at his Substack entitled “Nobody is talking about this in the Catholic world,” Patrick Giroux has the courage and good sense to raise the issue of the indiscriminate reception of the Lord at weddings and funerals where many attendees are not Catholics, or, if Catholics, not practicing, not in accord with Church teaching, or not in a state...