This article is a continuation of our series on the Mozarabic liturgy -- with a reminder, again, that while making some reference to the earlier liturgical books, we are primarily looking at the Mozarabic liturgy as it stood after the 16th century and the reforms of Cardinal Francisco Ximenes de Cisneros. I would make a further reminder that the intent here is not to cover all aspects or variances in a comprehensive manner, but instead guide one through the basic structure of the rite, while noting some points of interest along the way.

Previous installments in the series include:

The Mozarabic Rite: Introduction

The Mozarabic Rite: The Two Missals

The Mozarabic Rite: Introductory Rites and Lessons

* * * |

| Cardinal Francisco Ximenes de Cisneros |

In our previous consideration of the Mozarabic Missal, we looked at the introductory rites and lessons and left off with the

Lauda chant. We now turn our attention to the Mass of the Faithful where we are brought to what the Mozarabic Missal calls the

Sacrificium; a prayer and chant which is variable, approximating itself to the Roman offertory chant. (Though at this point I would bring to your recollection again an interesting discrepancy within the Mozarabic missal. While the

Omnium Offerentium places the

Sacrificium before the offering of the host and the chalice with its associated prayers, the other, which is found within the context of the First Sunday of Advent, sees this order reversed. For our purposes here, I will simply follow the textual order found within the

Omnium Offerentium.)

Archdale King notes

"that it was here that the offering of bread and wine by the people in the old Mozarabic rite took place. The priest removed the pallium (covering), which until then had covered the altar, and spread the corporal. The officiant then received the gifts of the people, with the bread offered in a linen cloth, and the wine in a cruet or other receptacle. Deacons poured wine into a large 'ministerial' chalice. Such of the offerings as were needed for the Mass were placed on the altar and covered with a veil of silk, which was known as the coopertorium, pall or palla corporalis. There was a prayer ad extendendum corporalia, but the various offertory acts were not accompanied by prayers. At the conclusion of the oblation, the sacred ministers washed their hands, and a signal was given for the chant of the sacrificium to cease." (Ibid., p. 591)

As was already noted in an earlier installment however, the actual preparation of the chalice in the later incarnation of the Mozarabic missal seems to have been somewhat akin to its position in the Low Mass of the Dominican rite, happening near the beginning of the Mass before the readings.

At this time the host and the wine are offered with the accompanied prayers.

Following this, the

Lavabo occurs and from there, an interesting rubric may be observed. The priest returns to the centre of the altar, and with

three fingers over the oblation prays quietly:

"In the name of the Father +, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, reign Thou O God, forever and ever. I will approach Thee in the lowliness of my spirit; I will speak to Thee because Thou has given me much hope in strength. Do Thou, O Son of David, Who revealing Thy mystery, didst come to us in the flesh, do Thou open the secret places of my heart with the key of Thy cross, and send one of Thy Seraphim to cleanse my defiled lips (He signs his lips) with that burning coal which has been taken from Thy altar to enlighten my mind (He signs his forehead) and to furnish me with the matter for teaching (He signs himself from his forehead to his breast) so that my tongue which serves to the help of my neighbours by charity, may not resound with the misfortune of error, but ceaselessly re-echo the praise of truth."At this point, we enter into the "seven prayers" spoken of by St. Isidore of Seville (A.D. 560–636) in

De Ecclesiasticis Officiis (Book 1, ch. 15), beginning with what the Mozarabic missal calls the

Missa -- which is variable to the liturgical day. These might be addressed to the faithful, to God the Father, or to Christ. An example of the prayer for the feast of St. James -- which is the Mass given within the

Omnium Offerentium as noted previously -- is as follows:

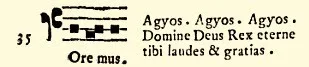

"O Christ whose might and power shone forth so conspicuously in Thy apostle James, that he merited to command with power in Thy name the hordes of demons cast out by him; do Thou defend Thy Church from the attacks of her enemies; so that in the might of her Spirit conquering adversity, she may indeed be rendered perfect by his teaching, whose example of holy suffering she honours today."After the conclusion of this prayer, it is at this point we see another quite interesting feature; we see the use of the Greek "Άγιος" (Agyos or Hagios):

"Hagios, hagios, hagios, Domine Rex aeterne, tibi laudes et gratias" - Holy, holy, holy, O Lord God, Eternal King, to Thee be praise and thanks. (Lest one think this is in place of the "Sanctus" as we think of it in Roman terms, it is worth noting that the

Sanctus is yet to come.)

After this one then proceeds into what Archdale King calls "a very compressed form of litany". The text is chanted.

"Let us bear in mind in our prayers the holy Catholic Church, that the Lord may mercifully deign to increase it in faith, hope and charity; let us bear in mind all the lapsed, the captives, the sick, and strangers, that the Lord may mercifully deign to look upon them, to ransom, to heal, and to strengthen them."

"Let us bear in mind in our prayers the holy Catholic Church, that the Lord may mercifully deign to increase it in faith, hope and charity; let us bear in mind all the lapsed, the captives, the sick, and strangers, that the Lord may mercifully deign to look upon them, to ransom, to heal, and to strengthen them."To which the choir responds:

"Grant, O Eternal Almighty God."Following this, a second proper prayer for the Mass of the day, the

Alia oratio, is then prayed and from here we are led into the chanting of the

Nomina or names:

"Through Thy mercy, O our God, in Whose sight the Names are recited of the holy apostles and martyrs, of the confessors and virgins. R. Amen.

"Offer they the oblation to the Lord God, our priests, the Roman Pontiff, and the rest, for themselves and for all the clergy, and for the peoples of the Church entrusted to them, likewise for the entire brotherhood. These also, all priests, deacons, clerics and people assisting, make the offering in honour of the saints, for themselves and for all theirs."To which the choir responds:

"They make the offering for themselves and for the entire brotherhood."Continuing, the priest chants (and one will note here a close approximation to the Roman

Communicantes):

"Making commemoration of the most blessed apostles and martyrs, of the glorious holy Virgin Mary, of Zacharias, John [the Baptist], the Infants [the Holy Innocents], Peter, Paul, John, James, Andrew, Philip, Thomas, Bartholomew, Matthew, James, Simon and Jude, Matthias, Mark and Luke."(The choir responds:)

"And of all martyrs"(The priest continues chanting:)

"Likewise for the souls of them that are at rest: Hilary, Athanasius, Martin, Ambrose, Augustine, Fulgentius, Leander, Isidore, David, Julian, also Julian of Peter, also Peter, John, Servideus, Visitanus, Vivens, Felix, Cyprian, Vincent, Gerontius, Zacharias, Coenapolus, Dominic, Justus, Saturninus, Salvatus, also Salvatus, Bernard, Raymond, John, Celebrunus, Gundisalvus, Martin, Roderic, John, Guterrius, Sanctius, also Sanctius, Dominic, Julian, also Julian, Philip, Stephen, John, also John, Felix."(The choir responds:)

"And of all them that are at rest."Archdale King comments that the Mozarabic

"diptychs are divided into classes: (1) the saints of the Old and New Testaments; (2) the names of bishops of the Church, as well as priests and clerics; (3) the names of certain bishops of other Churches renowned for their holiness or doctrine; (4) the dead for whom the holy Sacrifice was being offered... The choir respond Et omnium pausantium at the conclusion of the diptychs, as we find in the Celtic missal of Stowe." (

Liturgies of the Primatial Sees, p. 597)

After this comes the

Post Nomina which is again a proper, and thus variable dependent upon the Mass of the day.

It is at this point that the Pax comes within the Mozarabic liturgy, rather than after the consecration and prior to the communion as we see in the Roman liturgy and some other liturgical uses. The prayer which introduces the pax is likewise a variable proper it should be noted.

The rite of peace concluded, we now turn toward the prayers which most immediately lead up to the consecration. The priest chants,

"Introibo ad altare Dei mei" to which the choir responds,

"Ad Deum qui laetificat juventutem meum."Placing his hands over the chalice he says,

"Your ears to the Lord" and from here we enter into some texts which will be much more familiar to Roman ears, such as the "Sursum corda" -- though not necessarily in the same order and with some variation.

This then brings us to the Preface, or as it is termed in the Mozarabic books, the

Inlatio or

Illatio -- yet another prayer which is also variable. Of this King notes that

"the Mozarabic books offer the richest and most varied collection of prefaces, hardly a Mass without its own proper inlatio..." (Ibid., p. 604)

Here for example, is an excerpt from the text of the

Inlatio for the feast of St. James:

It is right and just that we always give thanks to Thee, Holy Lord, Eternal Father, Almighty God, through Jesus Christ, Thy Son, our Lord, in Whose name the chosen James, when he was being dragged to his passion, cured a paralytic who called out to him, and by this miracle so softened the heart of him who mocked him, as to cause him now imbued with the sacraments of faith to arrive at the glory of martyrdom. And so he himself having perished, by having his head struck off in the confession of Thy Son, attained in peace to Him for Whom he suffered this passion...

This brings us to the Sanctus which text is similar to that of Rome, but also shows forth some interesting variations:

Aside from the minor textual variation which includes "son of David", you will also note the inclusion, again, of the Greek:

"Hagios, hagios, hagios, Kyrie O Theos."This is then followed by the

Post Sanctus, which, yet again, is a variable prayer.

In the next installment, we shall continue looking toward the consecration and what comes thereafter.

Perhaps the next day I stumbled across this website,

Perhaps the next day I stumbled across this website,

.jpg)