With the visit of the Pope to Constantinople, there is some increased interested in the famed and historic church of the Byzantine Empire, Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom).

An interesting looking title on this subject is Hagia Sophia: Architecture, Structure, and Liturgy of Justinian's Great Church

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Hagia Sophia: Architecture, Structure, and Liturgy of Justinian's Great Church: Books: R. J. Mainstone

Shawn TribePatriarch of Constantinople on the Liturgy

Shawn TribeThis homily by Patriarch Bartholomew, Patriarch of Constantiniple, given in the presence is His Holiness, Pope Benedict XVI, includes some very good reflections on the sacred liturgy:"Every celebration of the Divine Liturgy is a powerful and inspiring con-celebration of heaven and of history. Every Divine Liturgy is both an anamnesis of the past and an anticipation of the Kingdom. We are convinced that during this Divine Liturgy, we have once again been transferred spiritually in three directions: toward the kingdom of heaven where the angels celebrate; toward the celebration of the liturgy through the centuries; and toward the heavenly kingdom to come.

"This overwhelming continuity with heaven as well as with history means that the Orthodox liturgy is the mystical experience and profound conviction that "Christ is and ever shall be in our midst!" For in Christ, there is a deep connection between past, present, and future. In this way, the liturgy is more than merely the recollection of Christ's words and acts. It is the realization of the very presence of Christ Himself, who has promised to be wherever two or three are gathered in His name."At the same time, we recognize that the rule of prayer is the rule of faith (lex orandi lex credendi), that the doctrines of the Person of Christ and of the Holy Trinity have left an indelible mark on the liturgy, which comprises one of the undefined doctrines, "revealed to us in mystery," of which St. Basil the Great so eloquently spoke. This is why, in liturgy, we are reminded of the need to reach unity in faith as well as in prayer. Therefore, we kneel in humility and repentance before the living God and our Lord Jesus Christ, whose precious Name we bear and yet at the same time whose seamless garment we have divided. We confess in sorrow that we are not yet able to celebrate the holy sacraments in unity. And we pray that the day may come when this sacramental unity will be realized in its fullness."

The Patriarch continues later on:

"Thus our worship coincides with the same joyous worship in heaven and throughout history. Indeed, as St. John Chrysostom himself affirms: "Those in heaven and those on earth form a single festival, a shared thanksgiving, one choir" (PG 56.97). Heaven and earth offer one prayer, one feast, one doxology. The Divine Liturgy is at once the heavenly kingdom and our home, "a new heaven and a new earth" (Rev. 21.1), the ground and center where all things find their true meaning. The Liturgy teaches us to broaden our horizon and vision, to speak the language of love and communion, but also to learn that we must be with one another in spite of our differences and even divisions. In its spacious embrace, it includes the whole world, the communion of saints, and all of God's creation. The entire universe becomes "a cosmic liturgy", to recall the teaching of St. Maximus the Confessor. This kind of Liturgy can never grow old or outdated."

Catholic World News : Pope, Orthodox Patriarch join for Divine Liturgy

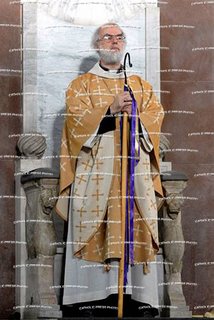

Shawn TribeNov. 30, 2006 (CWNews.com) - Pope Benedict XVI (bio - news) joined Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I in celebrating the Divine Liturgy on November 30, the promise that had brought him on his 4-day visit to Turkey.

Although the papal voyage has taken on a high public profile because of controversy over Islam and Christianity, and the Turkish government's bid for membership in the European Union, the original purpose of the trip was to join the Orthodox Patriarch in celebrating the feast of St. Andrew, the patron of the Constantinople see. The Holy Father had accepted an invitation from the Patriarch, issued shortly after his election, to travel to Turkey, in response to the Patriarch's own visits to Rome.

Pope Benedict was greeted at the patriarchal church of St. George, in the ancient Phanar section of Istanbul, with the ringing of the church's bells. He then joined the Patriarch in the Byzantine liturgy, with each prelate delivering a homily. After the ceremony, the Pope and the Patriarch joined in signing a joint declaration, affirming their commitment to the pursuit of full Christian unity. [See today's separate CWN headline story for a fuller account of the joint statement.]

In his homily during the Thursday service, Pope Benedict carefully expressed his deference toward the Constantinople patriarchate. He began by noting that St. Andrew, whose was being celebrated, was the apostle who brought his brother Simon to Jesus. And is referred to Rome and Constantinople as "sister churches." Still, later in his homily the Pope defended the primacy of Rome, observing that St. Peter traveled from Jerusalem to Antioch and then to Rome, "so that in that city he might exercise a universal responsibility."

The Pontiff acknowledged that the subject of papal primacy "has unfortunately given rise to our difference of opinion, which we hope to overcome." He recalled that Pope John Paul II (bio - news) had asked other Christian churches to suggest how the Petrine ministry should be exercised today, in a way that would ease the concerns of the Eastern churches without neglecting the papal responsibility for unity within the universal Church. Pope Benedict renewed that invitation.

"I can assure you that the Catholic Church is willing to do everything possible to overcome obstacles" to full Christian unity, the Pope said. He added: "The divisions which exist among Christians are a scandal to the world and an obstacle to the proclamation of the Gospel."

Turning to the prospects for immediate cooperation, the Pontiff observed that Rome and Constantinople can work together today to revive the Christian cultural roots of European society. "The process of secularization has weakened the hold of that tradition," he said; "indeed it is being called into question and even rejected." All Christians, the Pope said, share a responsibility "to renew Europe's awareness of its Christian roots, traditions, and values, giving them new vitality."

As he reached the conclusion of his homily, Pope Benedict offered a revealing meditation on the Gospel reference to the grain of wheat that dies in the ground in order to bear fruit in the long term. The Church in both Rome and Constantinople have "experienced the lesson of the grain of wheat," the Pope observed. He referred directly to the martyrs who died for the faith. But his reference might also have applied to the small Christian community in Istanbul, struggling to survive in a hostile community; or it could have applied to the Church of Rome, battling to preserve Christian culture in a steadily more secularized Europe.

Patriarch Bartholomew, in his own homily, did not directly address the practical questions of ecumenism, although he referred to the Pontiff as "our brother and bishop of the elder Rome." Instead the Orthodox prelate centered his remarks on the Divine Liturgy, and the lessons to be learned from the ceremony. "The Liturgy," he said, "teaches us to broaden our horizon and vision, to speak the language of love and communion, but also to learn that we must be with one another in spite of our differences and even divisions."

The Divine Liturgy, the Patriarch observed, points the Christian community in three directions: "toward the kingdom of heaven where the angels celebrate; toward the celebration of the liturgy through the centuries; and toward the heavenly kingdom to come." In this "overwhelming continuity with heaven as well as with history," he said, the Church finds the principle on which Christian unity must be based.

Pope Benedict in Constantinople

Shawn TribeThe Patriarchate of Constantinople has some wonderful pictures up of Pope Benedict and Patriarch Bartholomew in a liturgical context: the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom in honour of the Feast of St. Andrew the Apostle.

This is an important visit, it goes without saying. Also available off that site is video of the Patriarchal Divine Liturgy (courtesy of EWTN) and other such items.

It is, however, sorrowful to see the great Byzantine Patriarchate of Constantinople reduced to the small state it has been, knowing once the glory of the Church in this region.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Premonstratensian Rite: A Summary

Shawn Tribe[Summarized and condensed from the Catholic Encyclopedia and Archdale King's, Liturgies of the Religious Orders]

The Premonstratensian, or Norbertine, rite differs from the Roman in the celebration of the Sacrifice of the Mass, the Divine Office and the administration of the Sacrament of Penance.

The Missal

The Missal is proper to the Order and is not arranged like the Roman Missal. The canon [of the Mass] is identical, with the exception of a slight variation as to the time of making the sign of the cross with the paten at the "Libera nos". The music for the Prefaces etc. differs, though not considerably, from that of the Roman Missal. Two alleluias are said after the "Ite missa est" for a week after Easter; for the whole of the remaining Paschal time one alleluia is said.

The Breviary

The Breviary differs from the Roman Breviary in its calendar, the manner of reciting it, arrangement of matter. Some saints on the Roman calendar are omitted.

The feasts peculiar to the Norbertines are: St. Godfried, Confessor, 16 January; St. Evermodus, B. C., 17 February; Blessed Frederick, Abbot, 3 March; St. Ludolph, B. M., 29 March; Blesssed Herman Joseph, C., 7 April; St. Isfrid, B. C.,' 15 June; Saints Adrian and James, Martyrs, 9 July; Blessed Hrosnata, 19 July, 19; Blessed Gertrude, Virgin, 13 August; Blessed Bronislava, Virgin, 30 August; St. Gilbert, Abbot, 24 October; St. Siardus, Abbot, 17 November.

The feast of St. Norbert, founder of the order, which falls on 6 June in the Roman calendar, is permanently transferred to 11 July, so that its solemn rite may not be interferred with by the feasts of Pentecost and Corpus Christi. Other feasts are the Triumph of St. Norbert over the sacramentarian heresy of Tanchelin, on the third Sunday after Pentecost, and the Translation of St. Norbert commemorating the translation of his body from Magdeburg to Prague, on the fourth Sunday after Easter.

Besides the daily recitation of the canonical hours the Norbertines are obliged to say the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin, except on triple feasts and during octaves of the first class. In choir this is said immediately after the Divine Office.

[From Archdale King:] The 'Reform' of the Premonstratensian Liturgy:

The ancient [Premonstratensian liturgical] tradition rapidly lost ground after the death of Abbot Despruets (ob. 1596). His successor, Francis de Longpré (1596-1613), seemed at first inclined to follow the 'old paths', and in March 1603 he confided to John Lepaige, a religious of Prémontré, the task of re-editing the missal and office books according to the most reliable manuscripts of the Order. Two years later (1605), however, the general chapter expressed the desire to effect a harmony between the old customary and the new Roman books.

A breviary based upon that of Rome was published in Paris in 1608, but the work of compromise satisfied no one. A section of the Order wished to adopt the Roman rite in toto, while there were those who demanded a return to traditional usages. In the general chapter of 1618 the German abbots, especially those of Swabia, attempted to force the introduction of the liturgical books of the Pian reform. The majority of the chapter was averse to anything so drastic, although it was agreed to 'reform' the books on the same principles as those which had guided the Roman reformers. In the breviary: hymns and ferial antiphons were to be taken from the Roman book, and the chant of the Genealogy of our Lord at Christmas and the Epiphany was to be suppressed; while as regards the missal: votive Masses and Masses for the dead were to be altered, in order that they might approximate more closely to the Pian text; while sequences, except those for Christmas and some of the greater feasts, were to be abolished.

Peter Gosset, the abbot-general (1613-35), was directed to see that these measures were carried out. A new breviary appeared in 1621, and a missal in the following year (1622). Few changes were made in the breviary: hymns, antiphons and responsaries were not corrected, but there were alterations in the lectionary, common of saints, choice of psalms at vespers, and in certain of the chapters and prayers.

The work on the missal was more drastic, and the Order accepted the Ordinary of the Mass in its Pian form. The changes in the temporal included no more than the lessons for Advent and the introduction of the Roman arrangement for the concluding Sundays after Pentecost, but in the sanctoral few feasts remained unchanged beyond those for our Lady, the apostles and some of the more important solemnities; while feasts, borrowed from the Roman calendar, were substituted for traditional commemorations. Masses for the dead now conformed to the Roman model, save for some few survivals, and the series of lessons in the Missa quotidiana pro defunctis, distributed for the days of the week, was abandoned. Votive Masses (familiares), including those de Beata, suffered cuts and amendments, and the number of sequences was drastically curtailed. This suppression of sequences was prescribed by the general chapter of 1660, and in the missal, which appeared three years later (1663), Laetabundus for the three Masses of Christmas was the only sequence not to be found in the Pian book.

The reform of the liturgical books became general and definitive about 1650...

The breviary, in spite of some unnecessary 'romanising', remained of great traditional value. It was edited at Toul in 1711 and at Verdun in 1725 and 1741.

A decision to revise the Office according to the old traditions was made in the general chapter, held at Tongerloo in August 1927. A breviary was published at Malines in 1930, and a missal in 1936, both of which were approved by Rome. Some old rubrics, given up in the 17th century, were restored to the breviary, but the missal suffered little change.

The ordinarius, regulating the ceremonies of the liturgical functions, was until recently the exemplar of 1739 (Verdun). In 1943 the Belgian abbots in consultation at Tongerloo agreed that the new ordinarius should be in the nature of a via media. It was felt that... the restoration of many of the details in the primitive book was impracticable. On the other hand, the commission had a sincere feeling of respect for the traditional rite, and a desire to bring back some of the ancient ceremonies....

The ordinarius appeared finally in 1939, and has on the whole respected the tradition of the Order, although one may be permitted to regret some of the lacunae, as, for example, the absence of a rubric directing the celebrant to extend his arms in the form of a cross after the consecration.

Rites and Ceremonies (from Archdale King)

ASPERGES

The following form is observed: the celebrant turns first to the Sacrament house, if the Blessed Sacrament is not reserved on the high altar, and sprinkles it. Then, having aspersed the altar, he makes a circuit of it, where this is practicable. This done, the cross is sprinkled, and the aspergil handed to the deacon and subdeacon. The crucifer is aspersed, and, on double feasts, the assistants also.

A procession is prescribed on all Sundays and triple feasts, in the following order: acolyte with holy water; crucifer with the figure of the cross turned towards the community more archiepiscopo, and preceded on doubles by two taperers and a thurifer (two on triple feasts); sacred ministers; and, lastly, the community. Stations are made before entering the choir and at the step of the sanctuary.

INTROIT

The entry for the conventual Mass is made during the psalm verse of the introit, and on feasts, when the versicle is repeated three times, after the second repetition. One or two acolytes are required, according to the day, and the subdeacon carries the gospel-book.[3-243]

PREPARATORY PRAYERS

The Confiteor has by way of an addition: sanctis patribus Augustino et Norberto. The acolyte stands during these prayers holding his candle, and when two servers are required, they face inwards, one on either side of the sacred ministers. The candles are put down at the beginning of the Kyrie, as prescribed in Ordo Romanus II.[3-246]

KYRIE and GLORIA

It seems to have been the custom in the Order from the earliest days for the priest to say privately what was sung by the choir. The Kyrie is said in the middle of the altar, with the deacon on the right of the celebrant, and the subdeacon on the left. A cantor in a cope preintones the Gloria in excelsis on great feasts.

After the words suscipe deprecationem nostram the acolytes go to the sacristy, and the first server takes the chalice and the second the cruets. They are brought into the church during the first collect, unless it should be necessary to assist the subdeacon at the reading of the epistle, in which case it is during the Kyrie.[3-248] If the first server is not in orders, the chalice is held in a linen cloth (muffula linea). The vessels are placed on the credence, if it is a triple or double feast; otherwise in the centre of the altar.[3-249]

COLLECTS

The corporal is spread by the deacon during the collects or the gradual, whichever may be the more convenient.[3-250] The mediaeval ordinarius directed the deacon to wash his hands before unfolding the corporal at the offertory: diaconus, lotis manibus, displicet corporale.[3-251]

The deacon is told explicitly not to face the people at Dominus vobiscum: diaconus non cum eo se convertat,[3-252] and he is directed to raise the edge of the chasuble... The raising of the vestment was customary in the Cistercian rite, and also at Bursfeld and Soissons, where it was done by the subdeacon.

EPISTLE

The epistle is sung by the subdeacon, who stands between two acolytes and faces the people. At a sung Mass without assistant ministers, the priest may either sing the epistle himself or depute a reader vested in a surplice.

GOSPEL

The rites connected with the singing of the gospel have preserved the main features outlined in the Ordines Romani...

The celebrant was enjoined in the traditional rite to 'stand with fear' (cum tremore), a monition borrowed from the Cistercian, and reminiscent of the Eastern liturgies.

The portable lights were formerly extinguished after the gospel, and not re-lit until the conclusion of the Pater noster. Today the candles are permitted to burn throughout the Mass.

On feasts, when the creed has been intoned by the celebrant, each member of the choir kisses the closed gospel-book and is censed.

OFFERTORY

The ancient ceremonies connected with the making of the chalice have been described in the appendix. Today the corporal is spread on the altar during the creed, unless it has been done previously. The rubric directing the deacon to wash his hands before unfolding the corporal was omitted in the reformed ordinaries.

The book-stand is placed on the altar before the offertory, as the missal had been previously on the mensa. On feasts, when the vessels are on the credence, the subdeacon in a humeral veil brings them to the altar. Water is added to the chalice with a spoon, and in the old rite this was done by the deacon.

PREFACE

The deacon was directed in the mediaeval ordinarius to hold the missal during the preface,[3-289] but he is occupied today with the censing. The ordinarius of 1622 makes no mention of censing by the deacon, but the practice was restored in the edition of 1739, and given its present position: the deacon, standing behind the celebrant before the altar, censes three times towards the left and three times towards the right. Then, wherever this is possible, he makes the complete circuit of the altar, censing the while. If the Blessed Sacrament is reserved, the deacon three times censes the 'Sacrament house' (aedicula venerabilis Sacramenti) on his knees. This censing of the Eucharist may have been in the mind of the compiler of the traditional ordinarius... Finally, the deacon censes the subdeacon, gives the thurible to the acolyte, and is censed himself.

CANON

A standard candle is lit at the beginning of the canon in the conventual Mass on the epistle side of the altar, and extinguished the communio.

For more information:

Premonstratensian Chant

Archdale King on the Premonstratensian rite

A nice bit of liturgica for sale

Shawn TribeSadly, too much for me to be able to add it to my own library of liturgical reference resources, but perhaps someone else might like it for themselves. From Pro Multis books in the USA, a 1759 Missale Romano-Benedictinum -- or in other words, the Roman Missal as published for a Benedictine Monastery (and perhaps with the inclusion of more saints of the Order in the calendar). It looks to be in very fine shape. Possibly a bit over-priced (though I'm not certain) but at least having a bit of interest being "Benedictine" (there was no Benedictine rite or use incidentally, other than the Breviarium Monasticum), and for being in such fine shape.

Graduale now massively improved

Jeffrey TuckerThanks to the work of a volunteer solicited on this blog, the Graduale 1961 has been dramatically improved with left navigation tools. If you downloaded it already, download it again to get the improved one. Again, thanks go to CMAA.

Organ Solos in Advent

Michael E. LawrenceA (somewhat early) Happy Advent to you.

I was going through some organ repertoire this week in preparation for a number of Advent services for which I'm playing. There seems to be little organ repertoire for Advent for which I can get truly excited, save for the great works of J.S. Bach, especially Wachet auf and the several versions of Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.

Why is this so? Perhaps--perhaps--it is because the organ has not been used in solo fashion, if at all, during Advent, save for the past several decades, and for the past several centuries in the Protestant denominations. Musicam sacram specifically mentions Advent as a time during the year when the organ cannot be played solo. My understanding, however, is that the current Ceremoniale Episcoporum does allow for the use of organ solos.

However, rubrics aside, which is more fitting, to have organ solos during Advent or not? Bach is wonderful, but he wrote for another tradition, and his works could nonetheless be adopted for the eschatological weeks before Advent. It seems to me that the penitential character of Advent has been lost, and that it is sorely needed again. Could a sobering up of the music help this along?

What say you, friends?

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Matthew Alderman. Praeclarum calicem. Ink on Vellum. January 2006.

A graphic designed for a liturgical project from last year, commissioned by a member of a student organization at the University of Notre Dame. The chalice is a freely re-designed variation of a Renaissance-style model sold by Granda Liturgical Arts; the theme of the Instruments of the Passion on the vessel were an addition by the author.

More examples of my work can be found here (ink drawings - sacred subjects and portraiture), here (an award-winning hypothetical design for a seminary), here (a hypothetical design for a Chicago church) and here (other speculative architectural designs).

Blogosphere controversy over cathedral alteration

Shawn TribeCathNews: A Service of Church Resources, located in Australia, has a piece today (tomorrow in Australia), Blogosphere controversy over cathedral alteration, which reports on NLM writer and architect, Matthew Alderman's recent critique of the proposed renovation of Sydney's Cathedral.

On this matter of the renovation, certainly the two things which particularly strike me as concerning are the ambo and the altar.

In both cases the design is certainly a concern, and not terribly befitting.

Of an even greater liturgical concern with regard to the altar is the fact that its design will work fundamentally against the possibility of ad orientem celebration -- the celebration of the liturgy in which the priest and people together face in the same direction in the offering up of liturgical worship.

On the one hand, this tends toward a situation that wasn't envisioned by the Council -- this goes without saying. Second of all, while versus populum (Mass with the priest facing in the direction of the congregation) has been the de facto norm these past few decades (which was not of course mandated by the Council or the Church) this physical alteration, which would effectively set versus populum in stone at this cathedral (figuratively and literally), is coming at the very inopportune moment when a heightening awareness is becoming evident in Rome and elsewhere (much due to the scholarship of Fr. Uwe Michael Lang, C.O., represented in his work Turning Towards the Lord: Orientation in Liturgical Prayer) in understanding the theological, historical and liturgical benefits of a reclamation of ad orientem celebration of the liturgy in the Latin rite -- an in continuity with the universal liturgical tradition of the Church, Eastern and Western.

With the realistic prospect of a return (at least partial if not universal) of the practice ad orientem liturgical celebration, such an oversight seems to be a gross mistake -- not to mention highly undesireable from any liturgical perspective that operates within a hermeneutic of continuity, or which seeks a more faithful implementation of the Second Vatican Council.

Let us hope these things will be reconsidered and revisited.

A sign of the times?

AnonymousLet's hope so!

The Archdiocese of Mobile has graciously agreed to underwrite the Gregorian chant workshop taking place this coming Saturday, December 2nd. There will be no charge for participants.

Read more about the workshop here.

Mahrt Speaks

Jeffrey TuckerHere is an inspiring note from CMAA President Professor William Mahrt about the prospects for sacred music in our time. It does make you wonder who could possibly be happy about a future in which Marian antiphons are never sung, Introits like "Ad te levavi" and "Gaudete in domino" are never heard, and we are forever subject to the whims of the commercial publishing industry for what music we associate with the faith.

We would never put up with this in other aspects of our lives. If we go to see "My Fair Lady" on Broadway, we would be taken aback if the musical score where replaced with the theme from Dragnet or with children's playground songs. If we turned on our DVD of Star Wars and the music were Rolling Stones songs from the 1970s, we would consider it a ripoff.

It is even more true for ceremonies. Birthdays and civic patriotic events have music that is built into the structure of the event. And what of the little ceremonies in life, such as when we put a baby down to sleep? Lullabies. It must be. What if one day we awoke to find all of this mixed up or completely gone? "Stars and Stripes Forever" is sung at bedtime, and "Rock-a-bye Baby" played over the loud speakers at Baseball games, or, for inexplicable reasons, the people in charge of what music we hear rule out nothing except what is traditional. We would think that the world had gone mad!

How much more true when it comes to liturgy, our public worship? Do we wonder what happened to the "soundtrack" to the liturgical year? Who can possibly celebrate a future in which the music that grew up with the Roman Rite--which also happens to be the purest, holiest, and most beautiful of all music--were never heard again, were never again to be part of our liturgical consciousness? This makes no sense at all, and surely anyone who wishes for the best in the public worship of the Catholic Church can understand this point.

After decades of confusion about these matters, there is a growing sense that another restoration is desperately needed. What matters here are not big initiatives by international commissions or ominous rulings from the Vatican. Musical understanding takes place nowhere but in the individual heart. That means that our efforts need to need to be directed toward making sacred music a living presence in liturgy, one Mass at a time, one parish at a time.

It sounds like a daunting task, and it is. On the other hand, Christianity is a daunting task. Imagine what the first generation of Christians thought about this idea of spreading the faith to the whole world. They couldn't even so much as breath a world about their own loyalties without risk cruel torture and death. Surely they wondered just who is responsible for this far-flung idea of evangelizing the whole world.

Well, it happened because people had faith. They took risks. They believed and they acted. They followed the model of Jesus and made sacrifices. No one set out to build civilization. They set out to save their own souls and lead others to truth. And what happened? A new form of civilization came about--one heart and one soul at a time.

The prospects for sacred music may seem not good to us today but consider how much less we have to overcome than the first generation of believers after Christ. It all starts with one hymn in one Mass in one parish. That's where and how the rebuilding will take place.

Monday, November 27, 2006

Liturgical Thunder from Down Under

MatthewAn Unfortunate Renovation Afoot at St. Mary's, Sydney

Sydney possesses one of the few truly spectacular bits of the Gothic Revival on the Australian continent. Its massive cathedral was begun by the Puginesque convert William Wilkinson Wardell after fire claimed the previous church on the site in 1865, and not fully completed until the turn of the following century. At the moment, the rich and coherent fabric of the edifice is at risk through a well-intentioned but essentially misguided renovation of the chancel planned to coincide with the Pope's visit for World Youth Day 2007.

A view of the Cathedral's current main altar, in the context of its historic chancel.

Unlike most previous cathedral renovations, such as the complete liturgical Armageddon that Archbishop Weakland dropped on Milwaukee before his departure, the unfortunate of the design is not immediately apparent. Nor is it the result of a patently heterodox agenda; the theology behind it is hardly of the radical variety. Indeed, it's rather painful for me to criticize the design at all, being under the aegis of one of my personal heroes, Vox Clara's very own ex-footballer-turned-Cardinal, George Pell, who I once had the honor to meet at a reception in the headquartes of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre.

Let me make it clear that my remarks here are not a criticism of Cardinal Pell, this noble man, this strong and great prelate, who has toiled long and hard for the sake of the Church in the Antipodes. This work should not be construed as a comment on his long history of service, his unimpeachable orthodoxy, or his strong support of the proper translation of the Mass. Nor should that Most Eminent Lord be blamed for the individual, unsupervised choices of his designers. Any man who knows Cardinal Pell's work knows his devotion to the liturgy, both in its present-day and classical forms.

That being said, the choices being made in His Eminence's name, if not by him, are unfortunate. In the end, the renovation remains unnecessary. However, to undertake a renovation of a historic cathedral on short notice, and particularly during a time where the fate of the liturgy is once again up for grabs, seems at the very least imprudent. The problems of the design stem not from bad theology but from a misapprehension of the architect's original intention and a general inability on the part of the designers, rather than their patron, to grasp the essence of Gothic revival. Cardinal Pell deserves better from those he has charged to undertake this design.

Essentially, the problem is that there is no problem to solve. Nothing needs to be done to this church to make it perfect for the Pope's arrival.

View towards the sanctuary with the east window.

At first glance, the design apparently has much to recommend it. A broad new chancel, parclose screens, an altar with a proper footpace, and a new bronze ambo to be designed by a well-known artist, Nigel Boonham. However, God is quite typically in the details, and the details are sadly insensitive to the context they've been placed in here.

The wall-like partition of the new choirstalls risks relegating the old high altar to unjustifiable obscurity.

The original focus of the church, the window and its high altar, are poorly served by the massively beefed-up choirstalls that sever any connection between the old high altar and the new freestanding one. The placement of the choir behind the altar where clergy attending in quire formerly sat is a dubious liturgical proposition at best. The massive wainscoted stall-ends only succeed in turning the old chancel into an irrelevant appendix. Should the liturgical climate change in the near future, the new choirstalls would render the hemmed-in old high altar virtually impossible to use.

The proposed Altar of the Entombed Christ in perspective: the breadth of the altar, as well as its minimal footpace, suggest a future traffic-flow problem to be inevitable.

Another puzzling detail are the crude screens that surround the old ambulatory. I am, by nature, fond of the mystery brought by screens and liturgical curtains, but these new additions run counter to the openness prized by Wardell's design. They're Disneyland pseudo-Gothic. Up to a certain point one should applaud the designers for trying a little, at least; but we are reaching a stage in the liturgical renewal when more really has to be demanded from our architects. If screens are deemed necessary, a very handsome and transparent effect could be achieved by the use of gilded and wrought iron in harmony with the existing altar-rail. Proper seating within the chancel should also be provided for concelebrants and assisting clergy, and this should be considered first before the implementation of screens of any sort.

The basic outline of a screened chancel with substantial choirstalls could be achieved without destroying the original context by substituting iron for wood and adaptively re-using the existing benches with new pew-ends and a discrete stepped base that would leave enough of a passage between the main and high altars to create an appropriate visual link. Any new choirstalls should be designed to minimize the amount of platform-space in order to best show off the chancel's splendid mosaic floor, one of the cathedral's undoubted treasures.

Plan of proposed chancel re-ordering. The excessively narrow connection between the old high altar and the new main altar effectively makes any future ad orientem masses virtually impossible.

In addition to the layout of the new chancel, the iconography of the altar and ambo and their relationship to the sanctuary's other furnishings is muddled. One might well question the need for a freestanding altar at all; at the very least, the existing main altar has the virtue of being properly vested in a frontal, with an accompanying crucifix and candlesticks of appropriate substance atop the mensa.

The new design is to be applauded for including a predella--a broad platform or step round the base--but nonetheless this footpace is entirely too small to be of real liturgical use. It does not permit the circling of the altar at the incensation, and would make any attempt to celebrate ad orientem masses impossible. The extreme width of the altar, while otherwise unlikely to excite comment, is likely to cause problems of liturgical traffic-flow in the narrow sanctuary.

The altar proposed is liturgically unsuitable.

Decorated sculptural altars are already difficult to properly vest with antependia in the accepted liturgical fashion; furthermore, if the conceptual art is true to life, the abstracted sculptural decoration, especially the pillars and the mandorla around the figure of the Dead Christ, lacks the subtlety of similar works in the church.

The Pelican Ambo: a baffling exercise in misplaced and unduly novel symbolism.

The Pelican ambo, while likely to be beautiful piece of metalwork, nonetheless is equally symbolically awkward, and, as with most modern ambos, misnamed, as it is essentially a glorified reading-desk. The pelican's Passion imagery is alien to the long iconographic tradition of ambos. Furthermore, the iconography--which depicts a family of pelicans representing a Christian family living under the Gospel--shifts the emphasis from the proclamation of the Word to our reception of it, and exchanges the Christological symbolism of the pelican for a more horizontal one. Even when one sets aside the question of symbolic propriety, the Christian pelican is a creature of myth and legend and to depict it with the gawky zoology of the real thing divests it of its sacrificial majesty.

The cathedra: architecturally naive and not in line with current rubrics.

One final criticism concerns the cathedra. The proposed canopy has since been discontinued, and while I am quite fond of canopies, one has to face up to facts and admit they're no longer allowed. More to the point, putting a canopy over the bishop's chair when the altar stands naked, would be a remarkable display of symbolic insensitivity; in this instance, it can be chalked up to the superficial sort of Gothic being practiced by the renovators. (Sadly, a tester over the new main altar is probably also impossible.)

It would also be better, to stress the linkage of the cathedra to the altar, for it to be made of stone. Wooden cathedras are appropriate in churches where the choirstalls seat a cathedral chapter, but St. Mary's has none, and since the chancel is likely to house a robed lay choir, a wooden throne would be unsuitable.

Cardinal Pell is a great and good man, and one of the lights of the Church under the Southern Cross. He should not be blamed for these bad artistic choices, and indeed, for having the vision to consider Gothic forms at all in his renovation, he should be thanked. However, the Cathedral does not really need any changes at this point in history, and indeed, may be rendered redundant in a few decades. If the design must continue, the designers must more fully the challenge they have been given and seriously study the Gothic that Wardell derived so much beauty from in his original project.

The design has been undertaken at breakneck speed, to spruce up the church for the arrival of the Vicar of Christ. Still, this does not mediate the lesser quality of the work proposed, nor the lack of proper attention paid by the designers to certain liturgical questions. In this time of continued liturgical flux, my advice to the Cathedral is to wait a century or two, see which way the priest is facing, and then start worrying about redecorating. Otherwise the work may prove to be an intrusive addition to this most historic of Australia's precious and small patrimony of church architecture. Cardinal Pell, his cathedral, and Australia, deserve better.

Archdiocese of Genoa: on the Motu Proprio

Shawn Tribe[This document comes from the Archdiocese of Genoa. Thanks to a reader who pointed it out.]

Clarifications regarding an eventual promulgation of a "Motu proprio" to ease the application of the indult on the use of the Missal called of Saint Pius V

November 27, 2006

1) the Pope, due to his supreme authority, has the power to put in practice universally valid and binding juridical and pastoral acts

2) The legitimate and fruitful celebration of the Eucharist requires full ecclesial communion, of which ultimately the Supreme Pontiff is the guarantor, who personally received from the Lord Jesus Christ the mission to confirm the brothers in the faith (cfr. Lk. 22, 32; Mt 16, 17-19; Jn 21,15-18); therefore it is indeed the Bishop of Rome who presides, with great mercy and joy, universal charity, never ceasing to seek the unity of those who believe in Christ.

3) The Second Vatican Council did not abolish the Mass of St. Pius V nor asked it to be abolished; rather the Council asked the reform of the order as it clearly appears from reading the Constitution on Sacred Liturgy, chapter III, numbers 50-58 (cfr. EV 1/86-106);

4) The amplification of the indult regarding the so called liturgy of St. Pius V, is not equivalent in any way to rejecting the Second Vatican Council or the Magisterium of Popes John XXIII and Paul VI.

5) Pope Paul VI himself - who in 1970 promulgated the Roman Missal, according to the indications of the Second Vatican Council -, personally conceded to Padre Pio of Pietrelcina the Indult to continue to celebrate, publicly as well, Holy Mass according to the rite of St. Pius V, although since Lent 1965 the liturgical reform had been under way.

6) Pope John Paul II had already offered, on October 3, 1984, with the "Quattuor abhinc annos" Congregation of Divine Worship Letter (cfr. EV 9/1034-1035) the possibility to Diocesan Bishops of utilizing an Indult, by which Holy Mass could be celebrated using the Roman Missal according to the 1962 edition, promulgated by Pope John XXIII. Moreover the same Pontiff, with the Motu Proprio: Ecclesia Dei adflicta, (July 2 1988, cfr. EV 11/1197-1205), established,among other things, by force of his apostolic authority: "respect must everywhere be shown for the feelings of all those who are attached to the Latin liturgical tradition, by a wide and generous application of the directives already issued some time ago by the Apostolic See, for the use of the Roman Missal according to the typical edition of 1962"

7) In the Church since the IV century, different liturgies or rites are in force that, although answering different traditions and sensibilities, express the same Catholic faith; such variety is a tangible sign of the Catholic Church's vitality.

8) the Council of Trent did not will to unify with an act of authority the rites then existing in the Latin Church; in fact, based on the principle established by the same St. Pius V - who, at the request of the Council, acted the reform -, the churches and religious orders which had for at least two centuries their own rite of venerable tradition, could keep it. As years passed by, as a matter of fact, the Roman Rite affirmed itself, though not in an exclusive way; the case of the Ambrosian rite is an example of that, spread through some valleys of the Ticino (called "Ambrosian Valleys") and the entire Archdiocese of Milan, though, even there, with exceptions: Monza, Trezzo, Treviglio;

9) two valid expressions of the same Catholic faith -- that of St. Pius V and that of Paul VI -- cannot be presented as "expressing opposite views" and, thus, as mutually irreconcilable;

10) In liturgical ambit, the decisions and deeds of Popes - namely John XXIII, Paul VI, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI - and of Councils - Tridentine and Vatican II - cannot be presented in a conflictual way and, even less, as alternative to one another.

Original Source: ARCIDIOCESI DI GENOVA

Progress, Progress, Progress

Jeffrey TuckerAmy Welborn reports on one correspondent who said that her parish did NOT sing The King of Glory this past weekend, owing, she thinks, to the ridicule heaped on this song by the famed Youtube video. (Sadly, some comments report that the song still lives in some places.)

The Great Black and White Vocations Game

MatthewA splendid interview with Brother Dominic Legge, O.P., a recent recruit at the Dominican Province of St. Joseph, on the subject of vocations, the Eucharist, and all that good stuff, is available at www.dominicanfriars.org. Go down to October 22, and say that we sent you. Lest I need to remind you, the Dominicans of St. Joseph are the ones who have brought you the fine liturgies and vigils of the Dominican House of Studies at D.C., and thus need no introduction.

Capuce-tip to friend Arina G., and apologies for the delay.

Rome and Rowan Williams

Shawn Tribe[Submitted by a friend and reader of the NLM. There are certainly some hard questions here that must be asked, and are worth asking. SRT] Reports of the Anglican leader Rowan Williams’ liturgical celebration on Sunday in the Dominican Church of Santa Sabina in Rome seem to raise a number of issues. How can it be that an Anglican clergyman – with access to his own Anglican church building in Rome – can so publicly use a Catholic altar dressed in a chasuble and carrying a crosier? And what of the reportedly extraordinary participation of Catholic curial officials - “Canadian Fr Donald Bolen, an official at the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity with responsibility for the Reformed churches, proclaimed the Gospel at the Mass after having received Archbishop Williams' blessing”? Rowan Williams is an erudite man and surely knows the significance of this. And no doubt so too do those Catholics responsible for the celebration. But we are not in communion with Anglicans and it seems somewhat disingenuous if not scandalous so to blur the line between, a line defended over the centuries by the blood of the martyrs of England and Wales.

Reports of the Anglican leader Rowan Williams’ liturgical celebration on Sunday in the Dominican Church of Santa Sabina in Rome seem to raise a number of issues. How can it be that an Anglican clergyman – with access to his own Anglican church building in Rome – can so publicly use a Catholic altar dressed in a chasuble and carrying a crosier? And what of the reportedly extraordinary participation of Catholic curial officials - “Canadian Fr Donald Bolen, an official at the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity with responsibility for the Reformed churches, proclaimed the Gospel at the Mass after having received Archbishop Williams' blessing”? Rowan Williams is an erudite man and surely knows the significance of this. And no doubt so too do those Catholics responsible for the celebration. But we are not in communion with Anglicans and it seems somewhat disingenuous if not scandalous so to blur the line between, a line defended over the centuries by the blood of the martyrs of England and Wales.

Ad te levavi

Jeffrey TuckerOne of the reasons behind the Church's song is to convey the drama of the liturgical year in an audible way. This way, even if a person had no Missal, couldn't understand the homily, and had no access to scripture, the message of the faith could still penetrate. And though today we have printed material and access to a thousands of treatises at our finger tips, what we all miss is the musical score to the liturgical year that our ancestors knew so well.

After all, a person who knew the chant well could play a little game: name that day of the year in 4, 5, or 6 notes. But these days, even the most famed of all Proper chants are new to our generation. It's a sobering thought, but there is also some exciting about discovering new treasures week after week.

And so here is one for next week, "Ad te levavi," the introit from the first Sunday of Advent. The notes mark the beginning of the Church year. The tendency in the musical line is always up, up, up, lifting up our souls, waiting with expectation with eyes toward Heaven--notice the jubilant Deus meus--a musical line at once bright, beautiful, and mysterious, as if we are sure that something extraordinary and liberating is going to happen but we aren't entirely sure of the details.

To thee, O Lord, have I lifted up my soul: in thee, O my God, I put my trust; let me not be ashamed. Neither let my enemies laugh at me: for none of them that wait on thee shall be confounded. Show, O Lord, thy ways to me, and teach me thy paths.

I love listening to this primitive MP3 of this chant, even with the accompaniment. I vaguely hear what sounds like someone there is singing the chant along with the monks. Was there ever a time when people were so inspired by the sound of the new Church year that they would spontaneously join in singing? Could it become that familiar over the generations? I can easily imagine it.

Familiarity starts with the first listening. Pastors of souls should insist that this song be heard again this coming Sunday. Perhaps in a few years, it will only require someone to hum the first 6 notes and we will all know immediately: it's Advent!

St. Elias and the Byzantine Liturgy

Shawn TribeA very nice slideshow of images and sounds from famed St. Elias' Church in Brampton, Ontario, Canada, showing the Byzantine Divine Liturgy in all its glory, mystery and beauty.

While you're at it, you might enjoy:

Divine Liturgy, Ethiopian Orthodox, Jerusalem

Malankara Easter liturgy

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Towards the people? No, eastwards

Shawn Tribe[Via L'espresso -- an unofficial translation from the original Italian]

by Sandro Magister

The Pope's liturgical celebration office has made available the book of the liturgies of the next trip of Benedict XVI to Turkey.

Within it there is also the Byzantine rite Mass, properly called Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, at which the Pope will attend on November 30, in the patriarchal church of St. George at Fanar, in Istanbul.

In presenting the book, the pontifical master of ceremonies Piero Marini writes among other things:

"The celebration of the Byzantine Divine Liturgy, as of those of others Oriental Churches, is performed towards the East. The priest with all the faithful look towards the East from which Christ will come one day in His glory. The priest intercedes with the Lord for his people; he walks before the people towards the meeting with the Lord. There are several moments in which the priest turns towards the people: to proclaim the Gospel, in the dialog before the Anaphora, for the Communion with the Holy Gifts, and for all the blessings."

Marini could not have spoken better. It looks like we are reading a page from Fr. U. Michael Lang's book "Turning towards the Lord", concerning the issue of orientation in the celebration of the Mass.

The book caused scandal among the supporters of the congregation-Mass and of the altars turned towards the people. But it has Joseph Ratzinger's introduction, which is not bad to have as a defense attorney.

In fact even Marini seems to have joined in.

The Dominican Rite: A Summary

Shawn Tribe[Summary and simplification from 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia)

Origin and development

The question of a special unified rite for the order received no official attention in the time of St. Dominic, each province sharing in the general liturgical diversities prevalent throughout the Church at the order's confirmation in 1216. Hence, each province and often each convent had certain peculiarities in the text and in the ceremonies of the Holy Sacrifice and the recitation of the Office.

The first indication of an effort to regulate liturgical conditions was manifested by Jordan of Saxony, the successor of St. Dominic.

The first systematic attempt at reform was made under the direction of John the Teuton, the fourth master general of the order. At his suggestion the Chapter of Bologna (1244) asked the delegates to bring to the next chapter (Cologne, 1245) their special rubrics for the recitation of the Office, their Missals, Graduals and Antiphonaries, "pro concordando officio". To bring some kind of order out of chaos a commission was appointed consisting of four members, one each from the Provinces of France, England, Lombardy, and Germany, to carry out the revision at Angers. They brought the result of their labours to the Chapter of Paris (1246), which approved the compilation and ordered its exclusive use by the whole Order and approved the "Lectionary" which had been entrusted to Humbert of Romains for revision.

Another force preservative of the special Dominican Rite was the Decree of Pius V (1570), imposing a common rite on the universal Church but excepting those rites which had been approved for two hundred years. This exception gave to the Order of Friars Preachers the privilege of maintaining its old rite, a privilege which the chapters of the order sanctioned and the members of the order gratefully accepted.

Several times movements have been started with the idea of conforming with the Roman Rite; but these have always been defeated, and the order still preserves the rite conceded to it by Pope Clement in 1267. [NLM: until our own modern day of course with the adoption of the Pauline Missal by the Dominican Order]

The Dominican Rite, formulated by Humbert, saw no radical development after its confirmation by Clement IV. When Pius V made his reform, the Dominican Rite had been fixed and stable for over three hundred years, while a constant liturgical change had been taking place in other communities. Furthermore the comparative simplicity of the Dominican Rite, as manifested in the different liturgical books, gives evidence of its antiquity.

The collection of the liturgical books now contains: (1) Martyrology; (2) Collectarium; (3) Processional; (4) Antiphonary; (5) Gradual; (6) Missal for the conventual Mass; (7) Missal for the private Mass; (8) Breviary; (9) Vesperal; (10) Horæ Diurnæ; (11) Ceremonial.

With the exception of the Breviary, these books are similar in arrangement to the correspondingly named books of the Roman Rite.

Dominican Liturgical Year

The Dominican Breviary is divided into Part I, Advent to Trinity, and Part II, Trinity to Advent. Also, unlike the Tridentine usage of the Roman rite and similar to the Sarum rite and other Northern European usages of the Roman rite, the Dominican Missal and Breviary counts Sundays after Trinity rather than Pentecost.

The Dominican Missal (Missale Sacri Ordinis Praedicatorum)

The most important is in the manner of celebrating a low Mass. The celebrant in the Dominican Rite wears the amice over his head until the beginning of Mass, and prepares the chalice as soon as he reaches the altar. The Psalm "Judica me Deus" is not said and the Confiteor, much shorter than the Roman, contains the name of St. Dominic. The Gloria and the Credo are begun at the centre of the altar and finished at the Missal. At the Offertory there is a simultaneous oblation of the Host and the chalice and only one prayer, the "Suscipe Sancta Trinitas". The Canon of the Mass is the same as the Canon of the Roman Rite, but after it are several noticeable differences. The Dominican celebrant says the "Agnus Dei" immediately after the "Pax Domini" and then recites the prayers "Hæc sacrosancta commixtio", "Domine Jesu Christe" and "Corpus et sanguis", then follows the Communion, the priest receiving the Host from his left hand. No prayers are said at the consumption of the Precious Blood, the first prayer after the "Corpus et Sanguis" being the Communion. These are the most noticeable differences in the celebration of a low Mass.

In a solemn Mass the chalice is brought in procession to the altar during the Gloria, and the corporal is unfolded by the deacon during the singing of the Epistle. The chalice is prepared just after the subdeacon has sung the Epistle, with the ministers seated at the Epistle side of the sanctuary. The chalice is brought from the altar to the place where the celebrant is seated by the sub-deacon, who pours the wine and water into it and replaces it on the altar. The incensing of the ministers occurs during the singing of the Preface. Throughout the rite the ministers also stand or move into various paterns rather different those of the old Roman Liturgy.

[Some pictures of the Mass according to the Dominican rite.]

The Dominican Breviary (Brevarium Sacri Ordinis Praedicatorum)

[NLM: there is a difference between the breviary used before Pius X's reform, and shortly thereafter. Someone here referenced Bonniwell's history of the Dominican liturgy, and I believe the date given for the reform of the Dominican Breviary came in the 1920's. This source is the 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia. It would be good to confirm whether this description speaks of the Dominican breviary prior to, or after in response to Pius X's reform of the breviary.]

The Dominican Breviary differs but slightly from the Roman. The Offices celebrated are of seven classes: of the season (de tempore), of saints (de sanctis), of vigils, of octaves, votive Offices, Office of the Blessed Virgin, and Office of the Dead. In point of dignity the feasts are classified as "totum duplex", "duplex" "simplex" "of three lessons", and "of a memory".

There is no difference in the ordering of the canonical hours, except that all during Paschal time the Dominican Matins provide for only three psalms and three lessons instead of the customary nine psalms and nine lessons.

The Office of the Blessed Virgin must be said on all days on which feasts of the rank of duplex or "totum duplex" are not celebrated. The Gradual psalms must be said on all Saturdays on which is said the votive Office of the Blessed Virgin. The Office of the Dead must be said once a week except during the week following Easter and the week following Pentecost. Other minor points of difference are the manner of making the commemorations, the text of the hymns, the Antiphons, the lessons of the common Offices and the insertions of special feasts of the order.

There is no great distinction between the musical notation of the Dominican Gradual, Vesperal and Antiphonary and the corresponding books of the Vatican edition. The Dominican chant has been faithfully copied from the MSS. of the thirteenth century, which were in turn derived indirectly from the Gregorian Sacramentary. One is not surprised therefore at the remarkable similarity between the chant of the two rites.

Why Chant?

Jeffrey TuckerA number of commentators on this post--an article on Fr. L. Donnelly's efforts on behalf of sacred music--said they wanted to see the pamphlet the journalist was referring to. Here it is: Why We Are Singing Gregorian Chant.

Expansion of Anglican Use?

Shawn TribeWell why not throw on yet another rumour. The Motu Proprio, of course, has moved well beyond mere speculative rumour, that much should be a fact.

One can never be certain whether rumours come from legitimate sources, of if rather it is an attempt at a "self-fulfilling prophecy" -- create a rumour in hopes of having it come to pass.

Still, with our Holy Father, one never knows with these liturgical initiatives, knowing well his sensitivity to it and the cultural war which Christianity faces.

Another rumour coming from the rumour mill comes from the Times Online, Pope to throw open the 'Flaminian Gate' to Anglicans which speculates about some kind of corporate solution for "traditionalist Anglicans" disaffected with the continuing liberalization of Anglican practice and doctrine.

Personally, I should think that it might be more likely for the Pope to seek the expansion of the existing "pastoral provision" Anglican use as is in effect in the United States.

Saturday, November 25, 2006

The Carmelite Rite: A quick summary

Shawn Tribe[A summary and simplification from the Catholic Encyclopedia.]

The rite in use among the Carmelites since about the middle of the twelfth century is known by the name of the Rite of the Holy Sepulchre.

This Rite of the Holy Sepulchre belonged to the Gallican family of the Roman Rite; it appears to have descended directly from the Parisian Rite, but to have undergone some modifications pointing to other sources.

The reform of the Roman liturgical books under St. Pius V called for a corresponding reform of the Carmelite Rite, which was taken in hand in 1580, the Breviary appearing in 1584 and the Missal in 1587. At the same time the Holy See withdrew the right hitherto exercised by the chapters and the generals of altering the liturgy of the order, and placed all such matters in the hands of the Sacred Congregation of Rites.

A note on the Discalced Carmelites

The publication of the Reformed Breviary of 1584 caused the newly established Discalced Carmelites to abandon the ancient rite once for all and to adopt the Roman Rite instead [NLM note: which breviary I have seen titled the Breviarium Romano-Carmelitanum, which is not to be confused with the Carmelite rite. I believe they also opted to use the Missale Romanum rather than the ancient Carmelite rite.]

The Carmelite Missal

The ancient Carmelite Rite stands about half way between the Carthusian and the Dominican rites. It shows signs of great antiquity -- e.g. in the absence of liturgical colours, in the sparing use of altar candles (one at low Mass, none on the altar itself at high Mass but only acolytes' torches, even these being extinguished during part of the Mass, four torches and one candle in choir for Tenebræ); incense is also used rarely and with noteworthy restrictions; the Blessing at the end of the Mass is only permitted where the custom of the country requires it; passing before the tabernacle, the brethren must make a profound inclination, not a genuflexion.

In the Mass there are some peculiarities. the altar remains covered until the priest and ministers are ready to begin, when the acolytes then roll back the cover; before the end of the Mass they cover the altar again. On great feasts the Introit is said three times, i.e. it is repeated both before and after the Gloria Patri; besides the Epistle and Gospel there is a lesson or prophecy to be recited by an acolyte. At the Lavabo the priest leaves the altar for the piscina where he says that psalm, or else Veni Creator Spiritus or Deus misereatur. Likewise after the first ablution he goes to the piscina to wash his fingers. During the Canon of the Mass the deacon moves a fan to keep the flies away, a custom still in use in Sicily and elsewhere. At the word fregit in the form of consecration, according to the Ordinal of 1312 and later rubrics, the priest makes a movement as if breaking the host. Great care is taken that the smoke of the thurible and of the torches do not interfere with the clear vision of the host when lifted up for the adoration of the faithful but the chalice is only slightly elevated. The celebrating priest does not genuflect but bows reverently. After the Pater Noster the choir sings the psalm Deus venerunt genies for the restoration of the Holy Land. The prayers for communion are identical with those of the Sarum Rite and other similar uses, viz. domine sancte pater, Domine Jesu Christe (as in the Roman Rite), and Salve salus mundi. The Domine non sum dignus was introduced only in 1568. The Mass ended with Dominus vobiscum, Ite missa est (or its equivalent) and Placeat.

The Last Gospel, which in both ordinals serves for the priest's thanksgiving, appears in the Missal of 1490 as an integral part of the Mass.

The Carmelite Breviary

The Divine Office also presents some noteworthy features. The first Vespers of certain feasts and the Vespers during Lent have a responsory usually taken from Matins. Compline has various hymns according to the season, and also special antiphons for the Canticle. The lessons at Matins follow a somewhat different plan from those of the Roman Office. The singing of the genealogies of Christ after Matins on Christmas and the Epiphany gave rise to beautiful ceremonies. After Tenebræ in Holy Week (sung at midnight) comes the chant of the Tropi; all the Holy Week services present interesting archaic features. Other particularities are the antiphons Pro fidei meritis etc. on the Sundays from Trinity Sunday to Advent and the verses after the psalms on Trinity, the feasts of St. Paul and St. Laurence. The hymns are those of the Roman Office; the proses appear to be a uniform collection which remained practically unchanged from the thirteenth century to 1544, when all but four or five were abolished. The Ordinal prescribes only four processions in the course of the year: on Candlemas, Palm Sunday, the Ascension and the Assumption.

The calendar of saints, in the two oldest recensions of the Ordinal, exhibits some feasts proper to the Holy Land, namely some of the early bishops of Jerusalem, the Biblical Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and Lazarus. The only special features were the feast of St. Anne, probably due to the fact that the Carmelites occupied for a short time a convent dedicated to her in Jerusalem (vacated by Benedictine nuns at the capture of that city in 1187), and the octave of the Nativity of Our Lady, which also was proper to the order.

Cistercian Rite (Breviarium/Missale Cisterciense): A quick summary

Shawn Tribe[There is evidently a great deal of interest in the various rites of the Church, and in particular the lesser known Western rites. As such, I've determined to post some quick summaries of some of the basic differences, by simply pulling them off extant sources like the Catholic Encyclopedia. It is difficult to do much more without the original liturgical materials in front of you after all.

It's worth noting that in my piece recently on the Divine Office, I proposed an over-inflated idea of Romanitas has homogenized our Western liturgical rites and uses, both in the Missal and in the Breviary. (This should not be taken as a polemic against the See of Rome, which we indeed venerate.) Take note in this summary -- which I've re-arranged and taken from the Catholic Encyclopedia via Wikipedia -- the actions of General of the Cistercian Order, Claude Vaussin, in the middle of the 17th century.]

A Summary of the Cistercian Rite and its variances from the Roman

Prior to the 17th Century:

The Missal:

Prior to its later reform (in the middle of the 17th cenutury) there were wide divergences between the Cistercian and Roman rites.

i) The psalm "Judica" was not said, but in its stead was recited the "Veni Creator"; the "Indulgentiam" was followed by the "Pater" and "Ave", and the "Oramus te Domine" was omitted in kissing the altar.

ii) After the "Pax Domini sit semper vobiscum", the "Agnus Dei" was said thrice, and was followed immediately by "Hæc sacrosancta commixtio corporis", said by the priest while placing the small fragment of the Sacred Host in the chalice; then the "Domine Jesu Christe, Fili Dei Vivi" was said, but the "Corpus Tuum" and "Quod ore sumpsimus" were omitted.

iii) The priest said the "Placeat" as now, and then "Meritis et precibus istorum et onmium sanctorum. Suorum misereatur nostri Omnipotens Dominus. Amen", while kissing the altar; with the sign of the Cross the Mass was ended.

Outside of some minor exceptions in the wording and conclusions of various prayers, the other parts of the Mass were the same as in the Roman Rite.

In some Masses of the year the ordo was different; for instance, on Palm Sunday the Passion was only said at the high Mass, at the other Masses a special gospel only being said.

The Missal from the 17th century and onwards:

Under Claude Vaussin, General of the Cistercians (in the middle of the seventeenth century), several reforms were made in the liturgical books of the order. Since then, the differences between the Roman and Cistercian rites are not as substantial.

The Breviary:

Quite different from the Roman, as it follows exactly the prescriptions of the Rule of St. Benedict, with a very few minor additions. St. Benedict wished the entire Psalter recited each week; twelve psalms are to be said at Matins when there are but two Nocturns; when there is a third Nocturn, it is to be composed of three divisions of a canticle, there being in this latter case always twelve lessons. Three psalms or divisions of psalms are appointed for Prime, the Little Hours and Compline (in this latter hour the "Nunc dimittis" is never said), and always four psalms for Vespers. Many minor divisions and directions are given in St. Benedict's Rule.

The Holy Qurbana in Oxford

Lawrence Lew OP

'Qurbana' is the Syriac word for 'Offering' and this evening in Keble College chapel, with the kind permission of the chaplain, the Divine Liturgy in the Syro-Malankara rite was offered. I managed to discretely take a few photographs during the first parts of the Liturgy but there was such a palpable sense of holiness during the Anaphora (of St Xystus) that I could not bring myself to photograph those sacred moments.

In the photograph above, the gifts are prepared and offered up in the sight of God.

The Syro-Malankara Church is the third hierarchy of the Catholic Church in India. You may read more about its origins and history here. It is granted all the rights and privileges and its own liturgy and legitimate customs of the Antiochene Rite, and also administrative autonomy.

The Antiochene Rite is the Liturgy of St. James of Jerusalem, which was itself based on the traditions of the ancient rite of the Early Christian Church of Jerusalem, as the Mystagogic Catecheses of St Cyril of Jerusalem imply. This parent (Antiochene) rite includes the the Malankar Rite which is located in India, (some members of whom) reunited with Rome in 1930, and uses the Syriac and Malayalam languages in its liturgies. It is this rite which was celebrated in Keble this evening.

The Holy Qurbana was entirely sung and celebrated in Syriac, Greek, English and Malayalam. It was beautiful to hear the epistle sung expertly in Greek and especially to hear the priest sing the Lord's Prayer in Syriac, which we regard to be the closest extant language to Aramaic.

One stood throughout the liturgy, although at moments the priest performed the most profound prostrations before the altar, asking the Lord to accept his offering. Incense played a major part in the liturgy and the thurible was swung throughout for almost two hours, creating a 'veil' of smoke. At one point, the priest blessed the thurible and this is a distinctive part of Syrian liturgy. As one commentator explains: "The blessing of the Censer is considered to be one of the important moments in the Holy Qurbana. This is the time when the Priest blesses the censer three times in the name of each persons in the Holy Trinity which is an another version of the thrice-holy hymn."

"The blessing of the Censer is considered to be one of the important moments in the Holy Qurbana. This is the time when the Priest blesses the censer three times in the name of each persons in the Holy Trinity which is an another version of the thrice-holy hymn."

Indeed, the prayers for the blessing of the censer are proclamations of the faith in Trinity and the chains on the censer represent the Holy Trinity: The first chain stands for God the Father, the second and third chains represent the human and divine nature of the Son and the fourth chain represents the Holy Spirit.

The priest puts incense in the censer and grabs one of the chains and makes the sign of the cross over it and says: "Holy is the Holy Father". Grasping two more chains the priest proclaims: "Holy is the Holy Son" and finally he grasps the last chain and says "Holy is the Holy Spirit".

At the most solemn parts of the liturgy, a gentle ring of bells and the shaking of a liturgical fan symbolized the presence of the seraphim around the altar and the sound is likened to the fluttering of their wings.

At the epiclesis, the priest waved his hands over the bread and wine with a fluttering motion, signifying the descent of the Holy Spirit and the deacon admonished the people to stand in awe as the Holy Spirit is descending and hovering over the mysteries.

It was a great privilege to assist at this ancient liturgy which was celebrated simply but still filled me with awe and wonder at the Holy Sacrifice that was being offered.

Below are some more photos from the Holy Qurbana.

1. The priest offering of the chalice at the beginning of the Liturgy,

2. The priest at the altar and

3. The priest humbles himself before the altar as he prepares himself to offer the august sacrifice.

UPDATED: 25 Nov - a very short clip was uploaded to give you a sense of the atmosphere - the chant, the clink of the thurible, etc. I wish I'd recorded the Lord's Prayer in Aramaic but was just too entranced!

Friday, November 24, 2006

Chants of the Sarum breviary

Shawn TribeAn interesting initiative I just discovered comes from the Gregorian Institute of Canada (it looks to have been an Anglican initiative, at least in origin) wherein they are working to make available, in PDF format, the chants of the Sarum use breviary.

The introduction further explains this initiative.

I can't comment upon the technical and historical aspects of this initiative. Though perhaps others may have an insight.

Here is what the Catholic Encyclopedia has to say about the Breviarium ad usum Sarum itself:

The Sarum Breviary, like the Sarum Missal, is essentially Roman. The Psalter is distributed through the seven Canonical Hours for weekly recitation exactly as with us, though naturally the psalms (XXI-XXV) left over from the Sunday Matins and assigned by Pius V for the Prime of different ferias are, as in the Dominican and Carmelite Breviaries, marked to be recited together on Sundays in their old place at the beginning of that Canonical Hour. Nor in the Sarum Matins do there occur the short prayers termed Absolutions. On the other hand, a ninth Responsory always preceded the Te Deum which was followed by the so-called "Versus Sacerdotalis," that is to say, a versicle intoned by the officiating priest and not by a cantor. At least on festival days, a Responsory was sung between the Little Chapter and Hymn of Vespers. When there were Commemorations or Memories as they are called in the Sarum, Dominican and allied Uses, the "Benedicamus Domino" of Vespers and Lauds was twice sung; once after the first Collect, and once after the last of the Commemorations. Compline began with the verse "Converte nos Deus," the hymn followed instead of preceding the Little Chapter, and the Confiteor, as at Prime, was said among the Preces. The Compline Antiphons, hymn, etc., varied with the ecclesiastical seasons; but the introduction of a final Antiphon and Prayer of Our Blessed Lady closing the Divine Office (Divine Service, it was called at Sarum) is posterior to Sarum times. The Antiphons of the Sarum Offices differ considerably from those in the actual Roman Breviary, but both from the literary and from the devotional point of view the latter are in most instances preferable to those they have superseded. The proper psalms for the various Commons of Saints and for feast days are nearly always the same as now; but for the First Vespers of the greater solemnities the five psalms beginning with the word "Laudate" were appointed as in the Dominican Breviary. The order of the reading of Holy Scripture at Matins is practically identical with that of the Breviary of Pius V, though in the Middle Ages the First Nocturn was not as now reserved for these Lections only. An interesting feature of the Sarum Breviary is its inclusion of Scripture Lections for the ferias of Lent. The Lections taken from the writings of the Fathers and from the Legends of the Saints were often disproportionately long and obviously needed the drastic revision they received after the Council of Trent. The Sarum hymns are in the main those of the Roman Breviary as sung before their revision under Urban VIII and comprise by consequence the famous "Veni Redemptor" of Christmas Vespers and the "O quam glorifica" of the Assumption with one or two others in like manner now obsolete.

Fr. Lawrence Donnelly Strives for the Ideal

Jeffrey TuckerThis is just a wonderful story about one pastor who has decided to do great things in his parish, by fulfilling what the Church is asking for:

Taking parish music to the next level

By LAUREEN McMAHON

New directions in liturgical music are bursting forth at Vancouver’s St. Jude’s Church, offering parishioners and visitors the opportunity to more fully appreciate the richness of the Church’s heritage of sacred music.

The plan to spring open this musical treasure chest, says pastor Father Lawrence Donnelly, received a tremendous boost when acclaimed classical musician Michael Jarvis came to direct the parish music program earlier this year.

An early music specialist, Jarvis is acknowledged as one of Canada’s premier harpsichordists and is an accomplished fortepianist and basso continuo player whose performances are available on several CD labels.

The appointment followed on the heels of the installation of a pipe organ at St. Jude’s after a Saskatchewan church sold it to the parish “for a dollar!” said Father Donnelly.

Continue reading

Beauty, Catechesis and Conversion

Shawn TribeIn an address delivered to the directors and employees of the Vatican Museums, the Holy Father continues to lay out the importance of the sacred arts as a means of drawing people toward the faith, and as a tool for catechesis:"The approach to Christian truth through artistic or socio-cultural expressions, has a greater chance of appealing to the intelligence and sensitivity of people who do not belong to the Catholic Church, and who may sometimes nourish feelings of prejudice or indifference towards her. Visitors to the Vatican Museums, by dwelling in this sanctuary of art and faith, have the opportunity to 'immerse' themselves in a concentrated atmosphere of 'theology by images'." (Source: VIS-Press releases)

Comments such as these continue to highlight the importance of the liturgy being ceremonious, tasteful and beautiful, as well as the sacred arts that surround the liturgy and amplify the sacred realities.

Beauty often has a greater and broader evangelical reach than the most erudite treatise, and as well is far more likely to stir the soul. This is why the liturgy and the liturgical arts should be topmost in our concern and why their importance should not be written off as the mere concern of aesthetes.

Benedict's short address on Sacred Music